Table of Contents

- Work Details

- Program Notes by John Williams

- Recordings

- In Williams’ Words

- Quotes & Commentary

- Audio & Video

- Bibliography and References

Work Details

Year of Composition: 1974-1976, revised in 1998

Duration: 30′ ca.

Structure: Three movements – I. Moderato – II. Slowly (in peaceful contemplation) – III. Broadly (Maestoso) – Quickly

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 1 piccolo, 2 oboes (2nd doubling on Cor Anglais), 2 Bflat clarinets, 2 bassoons (2nd doubling on contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (vibraphone, glockenspiel, xylophone, marimba, chimes, suspended cymbal, piatti, small triangle, triangle, snare drum, bass drum), harp, strings

First Performance: January 29, 1981, at Powell Hall, St. Louis, USA

Soloist/Orchestra: Mark Peskanov, violin; Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Slatkin

Program Notes by John Williams

The 20th century has been an extremely rich period in the production of violin concertos. It is a period in which we have been given masterpieces of the genre by Bartók, Berg, Elgar, Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Walton and others. These works have set a very high standard for any composer wishing to contribute a piece of this kind. However daunting these examples of the recent past may be, the medium of the violin concerto continues to fascinate. The violin itself remains an instrument of enormous expressive power, and the urge to contribute to its repertoire is great.

With these thoughts in mind, I set to work laying out my concerto in three movements, each with expansive themes and featuring virtuosic passage work used both for effective contrast and display. The pattern of movements is fast, slow, fast, with a cadenza at the end of the first movement. Although contemporary in style and technique, I think of the piece as within the Romantic tradition.

The first movement starts with an unaccompanied presentation, by the solo violin, of the principal theme, which is composed of broad melodic intervals and rhythmic contour, in contrast with the more jaunty second subject. Orchestra and soloist share the exploitation of this material, and after the solo cadenza the movement is brought to a quiet conclusion.

The second movement features an elegiac melodic subject. While this melody is the central feature of the movement, there is, by way of contrast, a brisk middle section based on rushing “tetrachordal” figures that are tossed back and forth between soloist and orchestra. The mood of the opening is always present, however, as the rushing and playing about continue to be accompanied by hints of a return to the movement’s more introspective opening.

The finale begins with chiming chords of great dissonance from the orchestra, all of which pivot around a G being constantly sounded by the trumpet. The solo part commences immediately on a journey of passagework in triple time that forms a kind of moto perpetuo which propels the movement. In rondo-like fashion, several melodies emerge until insistent intervals, borrowed from the first movement, form to make up the final lyrical passage “sung” by the solo violin. An excited coda, based on the triple-time figures, concludes the work.

I began composing the concerto in 1974, finishing it October 19, 1976. It is dedicated to the memory of my late wife.

John Williams

Recordings

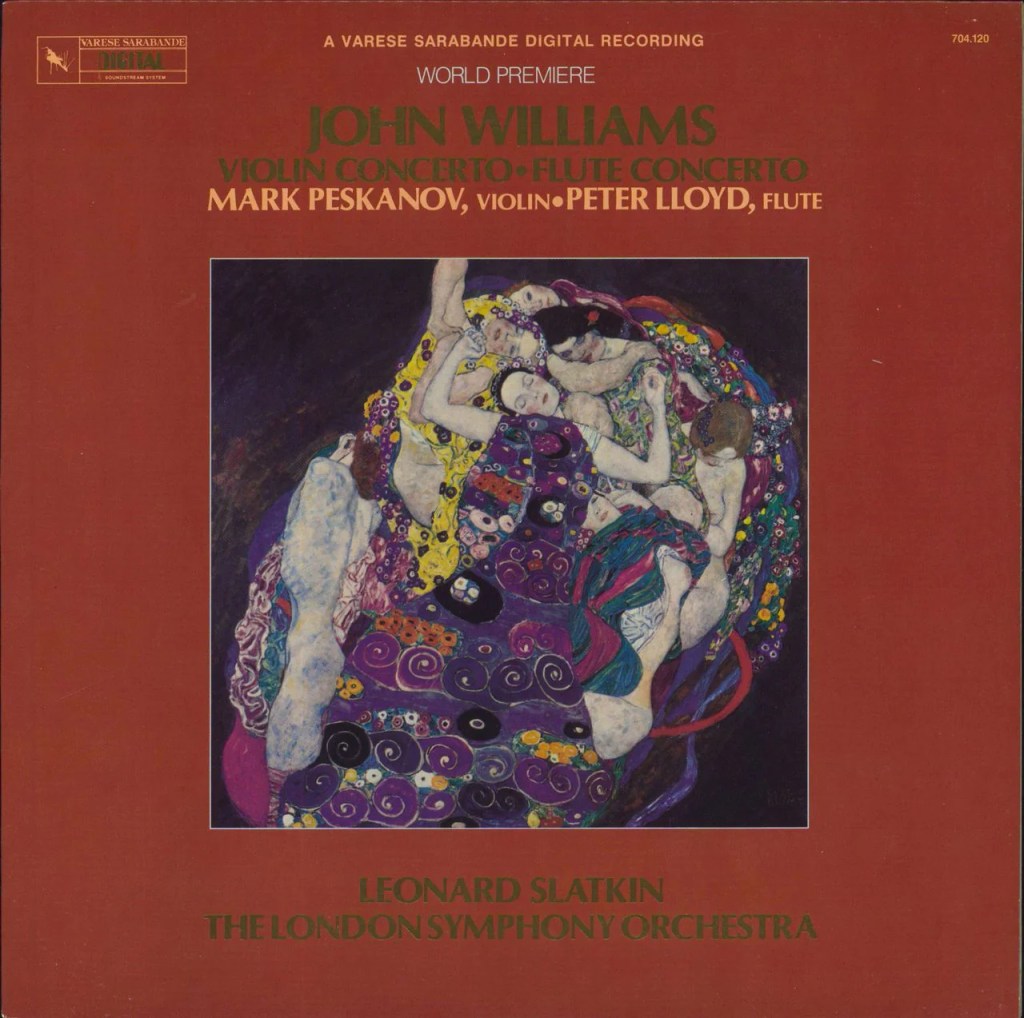

World Premiere Recording – LP (1983)

Varèse Sarabande VCDM 704.120-A

Reissued on CD in 1992 (Varèse Sarabande VSD-5345)

Mark Peskanov, violin; London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Slatkin

Produced by George Korngold

Engineer: Peter Bown

Recorded at Abbey Road Studios, London, December 13, 1981

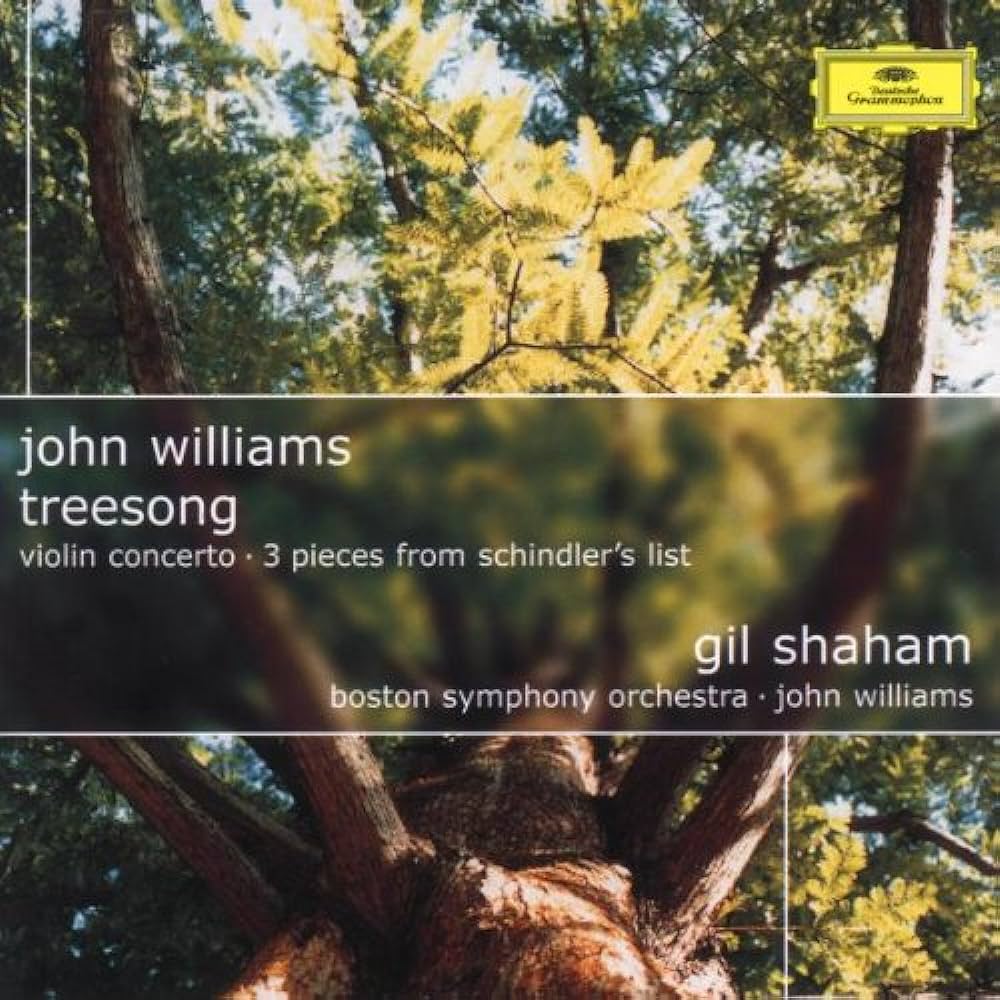

John Williams: TreeSong; Violin Concerto; 3 pieces from Schindler’s List – CD (2001)

Deutsche Grammophon – 471 326-2

Gil Shaham, violin; Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by John Williams

Produced by Christian Gansch

Engineer (Tonmeister): Stephan Flock

Recorded at Symphony Hall, Boston, October 1999

John Williams: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra – Digital-only release (2011)

Naxos Portara 9.70902

Emmanuel Boisvert, violin; Detroit Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Slatkin

Recorded live at Orchestra Hall, Detroit, 2010

In Williams’ Words

“I think [the Violin Concerto] is about the closest I’ve been able to come to a genuine, idiosyncratic expression. As I was working on that, I was just beginning to feel my wings—much more than the symphony or the wind works. I had more difficulty with style and idiom in those; with the Violin Concerto I was beginning to find a style which… it was still Romantic, but the kind of Romantic Atonality, in an American way, which I was seeking.” (1978)

“[My late wife Barbara] had loved the violin. Her father had been a violinist. On her death, I promised her I’d write a violin concerto. It’s not elegiac. It’s a virtuosic piece I think she would have liked. It’s joyous, actually, in its mood. It doesn’t reflect anything funereal. It celebrates one woman’s life.” (2004)

“The piece was written just after my my wife [Barbara] died in 1974 and she was a very young woman. Sadly, she was just 41 years old and we had teenage children at the time. It couldn’t have been more difficult to lose this lovely girl the way that we did. She loved violin, her father was an amateur violinist. And for quite a few years, we were married for 18 years, she would say to me, ‘Why don’t you write a piece for violin? Write something romantic for the violin,’ which of course I never imagined that I would, and I hadn’t. When she passed on, of course I stopped working because I felt I needed to be home with the children and try to help them adjust to what was a terrible blow to all of them, certainly to me. And while they were at school, sort of moping around the house a little bit, trying to think about how we would go forward in our lives, I began to make sketches for a violin concerto, thinking about what she might like. So, really, I wrote it for her. Alas, of course she’s never been able to hear it. And my hope at the time was that [violinist] Isaac Stern might be interested in the piece, and I remember he came to the house twice, and I played sections of it for him, and he was very encouraging about it. Alas, he never played it, but I mention him because he was friendly at the time, very empathetic about the whole situation that I faced, and as a result became interested in the piece. I suppose it is in a very Romantic style. I like to think it’s one that Barbara would have related to and enjoyed.” (2013)

Quotes & Commentary

I think sometimes listeners might be surprised when they hear the Violin Concerto. This is a very–I want to say somber, or I’m not sure what the right word would be–there is a dark quality to the piece. And it’s certainly a concert work, it’s not music for a film. I love the piece. I’ve been very lucky to have worked on it with John. And we’ve performed it several times, and we even recorded it [in Boston]. I’m a great fan and I love his writing. But he always says, “Composing music is like working in a kitchen.” You know, he says there’s always something to do. You always go back here and change a little or do something there. And that’s been the case with this Violin Concerto. I find the piece to be incredibly moving. It starts with this very dark, almost minor quality, although it’s not exactly in a tonal vein, sort of a B-flat going up to a G-flat in a sixth. And this very compact gesture is kind of the seed for the whole piece and by the end of the third movement, it transforms. And there’s an incredible moment, the sort of apotheosis of the piece, where it’s inverted into a minor third, but it has a major quality because it’s G-sharp and B-natural, and the violin takes over this tune, this time with a whole orchestra, the force of the entire orchestra behind the violinist. It really takes the listener on an incredible journey.

– Gil Shaham, violinist

It’s interesting because [the Violin Concerto] is definitely his signature style, which is to be extremely lyrical. For me he has, first, one incredible gift, which is a melodic gift, it’s something so rare, so few composers just are able to write really successful melodies. And he did many in his career. And this concerto has a lot of fabulous melodies. But the overall language is certainly less tonal, and it’s slightly modernistic in its choice of notes, of pitches. Also the way it’s structured is very different because when you do a big format, like a 30-minute concerto, you need to have a very complicated structure and work the the thematic material in a certain way, which you cannot do in a movie. And so of course, this is a masterwork and it’s very rich in its organization of the different moments and different melodies. So I would say you can recognize definitely that [it’s] the same man and especially in this generous lyrical aspect.

– Stéphane Denève, conductor

Williams began his Violin Concerto in 1974 and completed the orchestration in October 1976. Mark Peskanov was soloist in the first performance, on 29 January 1981, with the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Slatkin. Williams subsequently revised the work, which reached its present form in 1998. The score is dedicated to the composer’s late wife, the actress and singer Barbara Ruick Williams. Its general tone is not, however, that of an elegy. Williams takes his cue from such 20th-century predecessors as Bartók, Prokofiev, and Walton in writing a three-movement, post-Romantic concerto that exploits the violin’s historical and technical resources for the purpose of expressing many different emotional perspectives. These range from the mysterious, almost haunting opening theme, presented by the soloist nearly without accompaniment (the first few bars over a pianissimo pedal E flat in the low strings), a second theme in the first movement described by the composer as “jaunty,” and a scherzo-like figure in the finale to a middle movement actually having the plaintive character of an elegy. Williams’s orchestration shifts kaleidoscopically, coloring, commenting upon, and supporting an almost continuous solo part.

The work begins with a melody for the soloist that covers more than two-and-a-half octaves in just a few measures. Led by the flute, the orchestra then repeats the opening theme while the solo violin accompanies with an active countermelody; this kind of give and take prevails throughout the concerto. A propulsive second theme in 16th notes (semiquavers) lightens the movement’s palette. Williams has written out a solo cadenza, which occupies a traditional position just prior to the quiet ending. This leads into the affecting second movement (marked “in peaceful contemplation”), whose gently rocking orchestral accompaniment foreshadows an almost frenetic passage later in the same movement. The return to the main theme, taken by a solo flute with countermelody in the solo violin, illustrates the composer’s supple and finely detailed use of orchestration. The finale, a nod to the traditional meshing of scherzo and rondo, begins with chiming, dissonant chords juxtaposed with the rhythmically exultant solo part. This material returns again and again, alternating with other themes and often laced with references to the first two movements. A coda based on the fast scherzo-like music ends the work.

– Robert Kirzinger, BSO Director of Program Publications

Audio and Video

Bibliography and References

. Elley, Derek – “The Film Composer: John Williams – Pt. 1 and Pt. 2,” Films and Filming, July/August 1978

. Kirzinger, Robert – Liner notes for John Williams: TreeSong, Violin Concerto, 3 pieces from Schindler’s List, Deutsche Grammophon, 2001

. Lewis, Susan – Arts Desk: Another Side to Film Composer John Williams, WRTI Radio Philadelphia, October 31, 2016

. Macleod, Donald – John Williams: Composer of the Week, BBC Radio 3, January 2012

. McCreath, Brian – Shaham, the BSO, and a Concerto by John Williams, Classical Radio Boston, March 2016

. Oksenhorn, Stewart – “The Man Who Loved Conducting,” The Aspen Times, July 16, 2004

. Schneller, Tom – “Out of Darkness: John Williams’s Violin Concerto,” in John Williams: Music for Films, Television and the Concert Stage (curated by Emilio Audissino), Brepols, 2018

. Svejda, Jim – The Evening Program: John Williams Discusses His Concert Works, Classical KUSC Radio, April 25, 2013

Legacy of John Williams Additional References

Journey to the Concert Hall – Essay by Maurizio Caschetto