Table Of Contents

- Film Details

- Music Credits

- Essential Discography

- In Williams’ Words

- Quotes and Commentary

- Videos

- Bibliography and References

Film Details

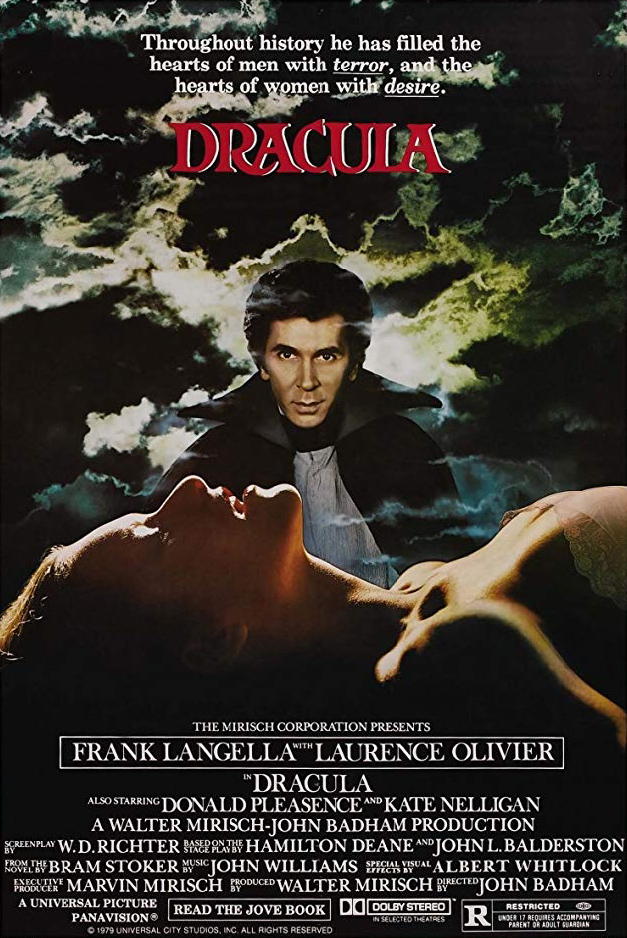

Year: 1979

Studio: Universal Pictures/The Mirisch Corporation

Director: John Badham

Producer: Walter Mirisch

Writer: W.D. Richter, based on the stage play by Hamilton Deane and John L.Balderston from the novel by Bram Stoker

Main Cast: Frank Langella, Laurence Olivier, Donald Pleasance, Kate Nelligan, Trevor Eve, Jan Francis, Tony Haygarth

Genre: Horror – Fantasy – Romance

For synopsis and full cast and crew credits, visit the IMDb page

Music Credits

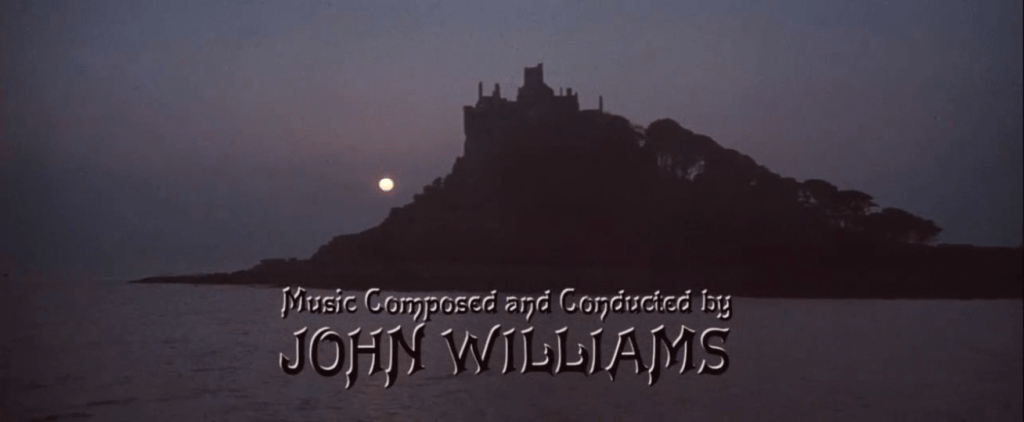

Music Composed and Conducted by John Williams

Performed by the London Symphony Orchestra

Concertmasters: Michael Davis and Irvine Arditti

Trumpet Solos: Maurice Murphy

Music Editor: Ken Wannberg

Recording Engineer: Eric Tomlinson

Orchestrators: Herbert W. Spencer, John Williams

Assistant Engineer: Alan Snelling

Recorded at Anvil Film and Recording Group, Denham, Middlesex

Recording Dates: April 24 and 30, May 1, 4 and 16 1979

Essential Discography

Original Soundtrack Album and Expanded Reissues

Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (LP, 1979)

MCA Records – MCA-3166

Produced by John Williams

Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (CD reissue, 1990)

Varèse Sarabande VSD-5250

Prepared for release by Robert Townson and Tom Null

The Deluxe Edition (2018)

Limited Edition 2-CD set

Varèse Sarabande VCL 1018 1188

Produced by Robert Townson and Mike Matessino

Restored, Edited and Mastered by Mike Matessino

Expanded film score plus bonus tracks on Disc 1; remastered reissue of the 1979 OST album on Disc 2

Selected Re-recordings

Hollywood Nightmares (1994)

Philips Digital Classics 442 425-2

contains “Night Journeys” from Dracula

Hollywood Bowl Orchestra conducted by John Mauceri

Lights, Camera… Music! Six Decades of John Williams (2017)

BSO Classics – 1704

contains “Night Journeys” from Dracula

Boston Pops Orchestra conducted by Keith Lockhart

Across The Stars (2019)

Deutsche Grammophon 479 7553

contains “Night Journeys” from Dracula (Violin Version)

Anne-Sophie Mutter, violin

Los Angeles Recording Arts Orchestra conducted by John Williams

In Williams’ Words

“I always felt that Dracula was a very erotic story. Certainly the way John Badham directed it, I felt that that was so. [Dracula is a] wonderful subject for music really, for the the sweep and arc of a kind of romance in areas that we are uncertain about, and odd worlds that we are attracted to, but we may be a little bit afraid of it at the same time. The magnetism of the unknown, mixed with the erotic aspects of the story, made it for me a very romantic piece in many ways.

“A horror film, maybe in in the sense of timing of events, is not dissimilar to comedy. In comedy, we have to deliver the joke exactly at the right time, or deliver a musical accent just when we expected it or not. I think in a horror movie it’s very similar. We have to deliver the attack, both editorially and musically, just at the right moment. If it comes a little too late, we’re asleep, if it comes too soon, we’re not quite enough. So there’s an art of sleight of hand, really, of magic. Dracula is certainly a very good illustration of the importance of timing in these things.”1

Quotes and Commentary

On a morning in late March of ’79 John Williams appeared at my house in California to view the first cut of Dracula. Though he had been commissioned almost a year previously to compose the score this was his first opportunity to see the film.

As we were about to begin he confessed he had never seen a vampire film of any sort before. Somehow he had managed to stumble upon full adulthood without having been exposed to the veritable gauntlet of Dracula films produced in the last fifty years. Not a foot. Not a frame. Not a sprocket hole. Incredible!

“Delighted to hear it,” was my reply, and we began the film. How fortunate to have the pre-eminent film composer of the day arrive with no advance notions of the kind of ketchup and thunder music that prevails in the horror film genre.

When the film was over, he turned and said. “Great. Now, can I see it again?” And we ran it again. And Again. Every morning in fact for a week the screams of Dracula’s victims resounded through the Canyons as John immersed himself in the textures and ambiences of the film.

Almost no conversation took place. Occasionally, aiter three days he would say things like “I think I’ll play during this part, is that alright?” Well of course it’s alright. But what kind of music? It is nearly impassible to describe music verbally. No one can read any known account of any piece of music and have more than a vague idea of what the music sounds like. Imagine the muddled and obfuscated conversation between us as John tried to get a fix on what I wanted for the film.

So I had to wait weeks while John worked over his piano. Reams of puzzling little notes on paper began to emerge daily on a trip to the orchestrator and thence to the copyist. Finally seeing a desperate director hovering at his door John took pity and played the haunting Dracula love theme he had composed.

There I could hear the piano’s imitation of what would eventually be a fully orchestrated, fully glorious piece of music. When the London Symphony Orchestra got its collective teeth on the music in May they played a score that is wildly romantic, shamelessly so. The nineteenth century romantics could all say they had a descendant living late in the 20th Century. Operatic in scale, it surrounds and elevates this often told tale of the Vampire King who takes a Queen for himself.

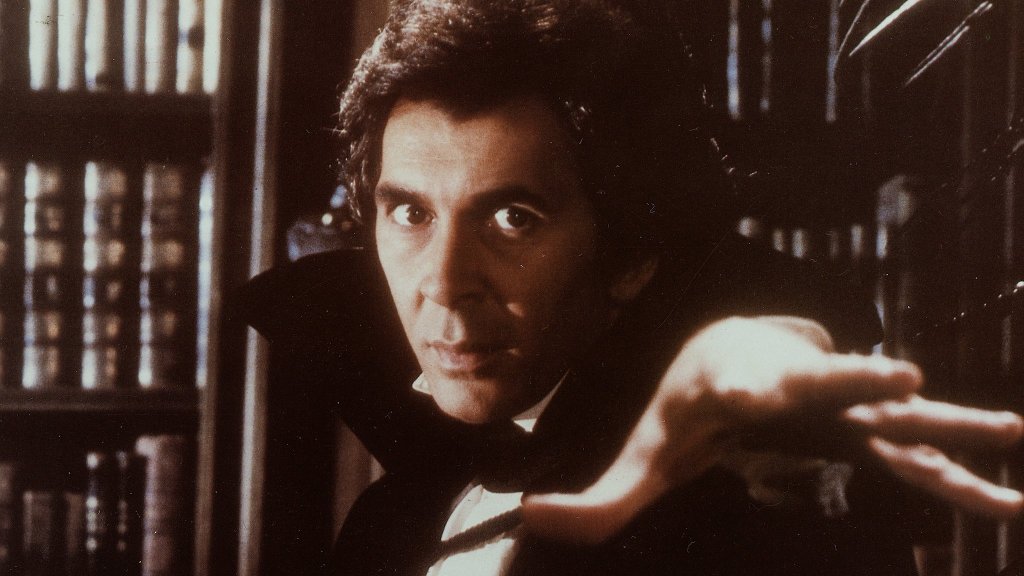

Puccini, Verdi, Berlioz all blew it. What a great subject for an opera. The emotion, the passion the terror all here to support and enhance a most unusual portrayal of Dracula by Frank Langella, A Byronic Dracula. A Dracula with an electric presence. The legends say the Devil gave Dracula eternal life in exchange for a steady re-routing of souls to Hell. Now the Devil is clever and knew that old saying about catching more flies with honey than vinegar. Did he pick an ugly man? An evil looking one? One with fangs? A debauched one? Never! Only the best for the Devil. He picked a handsome warrior, a charismatic leader, the conqueror of the Turks in the 15th Century. in short, one that knew how to get girls.

Film music and the films they go with often cannot stand alone. They are weakly interdependent. This is never true of John’s score which stands on its own as do all his scores. The proof of course, is how frequently they are played by symphony orchestras around the world. This score most certainly will join his music for Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Jaws, and many others as another great example of the film composer’s ability to stand with dignity and stature in the world of serious music.2

– John Badham

Fortunately, John Williams’ score enshrouds some of the film’s deficiencies, and ranks as one of the finest of 1979. The texture of the music is symphonic; the style avowedly romantic. Williams’ approach was to compose a theme for Dracula, and base the resultant score on a set of variations of that theme: the “Main Title” introduces the dramatic Dracula leitmotif, which anticipates Langella’s interpretation and helps unify the film; “Night Journeys,” offers an effusive elaboration of Dracula’s theme. Although there are other compelling variations, Williams provides additional divergent material to further add to the thematic variety of the score. For example, one of Williams’ strengths as a composer is his ability to write scherzos. “To Scarborough” is a short but energetic piece that ranks with his best, and paces the scene to an exciting finish.

In a primarily intense score, Williams does interpolate a degree of calmness: “For Mina” features an elegiac trumpet solo and contemplative string writing. The composer returns to his major theme in the climactic “Dracula’s Death,” where the development reaches operatic proportions. The score concludes with the “End Title,” an expressive epilogue which provides a furious coda to the film.

Because of composers like John Williams, who are interested in the endless possibilities of audio-visual synchronization, scores like Dracula speak volumes for the importance of first-rate original film composition. Unlike the film, Williams eschews the conventions of the Hollywood horror genre. His music will be remembered as another score superior to the film for which it was written. Fortunately, Williams’ recorded presentation of the score illustrates another important argument: that film music can stand on its own as serious composition.3

– Kevin Mulhall

In his score, John Williams employed a quintessential 19th-century idiom that encapsulated the tone of the original story, eschewing all evidence of modernism as befitted the post-Edwardian British setting of the film. The soundscape is grounded in clear associations with the macabre, brooding low tones to suggest death and decay, tense sustained atmospheres for crypts, decrepit castles and foggy moors, screeching violins and piccolos to depict attacking nocturnal creatures and even the occasional pipe organ-sounds that so definitively capture an entire genre that they might as easily accompany any tale by Poe, Lovecraft or Shelley as well as Stoker. In Dracula these elements all support Williams’ stunning principal melody, a minor-mode, darkly seductive love theme that constantly reaches higher and higher, searching for transcendence, full of brash confidence but somehow

tormented and never able to find fulfillment.

Until “Night Journeys,” that is.

This is the score’s remarkable centerpiece cue (“The Love Scene” on Williams’ manuscript), in which the minor key theme begins tentatively, even tenderly, then builds erotically to a climactic major chord as fulfilled as any ever composed. It is the moment that defines what this film and the 1970s stage play, both via Langellas mesmerizing persona, brought to the Dracula mythos: the unbridled sexuality that in prior adaptations had been sidelined in favor of monstrous horror. Badham’s film and Williams’ music at last explore the tragic side of Dracula: that he is a creature of immortal youth, physically flawless in appearance, gifted with powers of seduction he’s had centuries to perfect, free to pursue carnal ecstasy with absolutely no consequences. But this dream of an idea comes with a terrible price: he is a being devoid of earthly substance, casting no reflection and unable to enjoy even the simple pleasures of sunlight and fine cuisine, and, most cruelly, doomed to never experience true love. A creature with no soul, after all, can never have a soulmate.

But then, his entire universe shifts when Lucy Seward willingly admits her feelings and devotion to him before learning of his true nature. It is a remarkable moment for the character, cinematically expressed in a sequence for which Badham commissioned Maurice Binder, designer of the impressionistic title backgrounds for the James Bond series. In it, Dracula and Lucy consummate their relationship in a way that suggests they have truly found a love that is eternal… in the literal sense of the word: “outside of time.” In more ways than one, this “raises the stakes” beyond all versions of the Dracula story that had come before.4

– Mike Matessino

Videos

The Revamping Of Dracula, DVD featurette (music discussion excerpt)

Directed and Produced by Laurent Bouzereau

Universal Studios Home Entertainment, 2002

Night Journeys (film clip with isolated score)

Universal Pictures/The Mirisch Corporation

John Badham Discusses a Scene from Dracula (Blu-ray bonus feature excerpt)

Scream Factory, 2020

Bibliography and References

. Audissino, Emilio – “Dark Neoclassicism – The Sublime Score to Dracula” (Chapter 11). The Film Music of John Williams, University of Wisconsin Press, 2021

. Bouzereau, Laurent – “What Sad Music He Makes – Interview with John Williams”. Little Shoppe of Horrors #36, Elmer Valo Appreciation Society, 2016

. Matessino, Mike – “Nocturne: John Williams and Dracula“. Liner notes for Dracula: The Deluxe Edition, Varèse Sarabande, 2018

Footnotes

- “What Sad Music He Makes – Interview with John Williams.” Little Shoppe of Horrors #36, 2016 ↩︎

- Dracula – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack sleeve notes, MCA Records, 1979 ↩︎

- Mulhall, liner notes for Dracula – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (CD reissue), 1990 ↩︎

- Matessino, Liner notes for Dracula: The Deluxe Edition, Varèse Sarabande, 2018 ↩︎