Table Of Contents

- Film Details

- Music Credits

- Essential Discography

- Awards and Nominations

- In Williams’ Words

- Quotes and Commentary

- Videos

- Bibliography and References

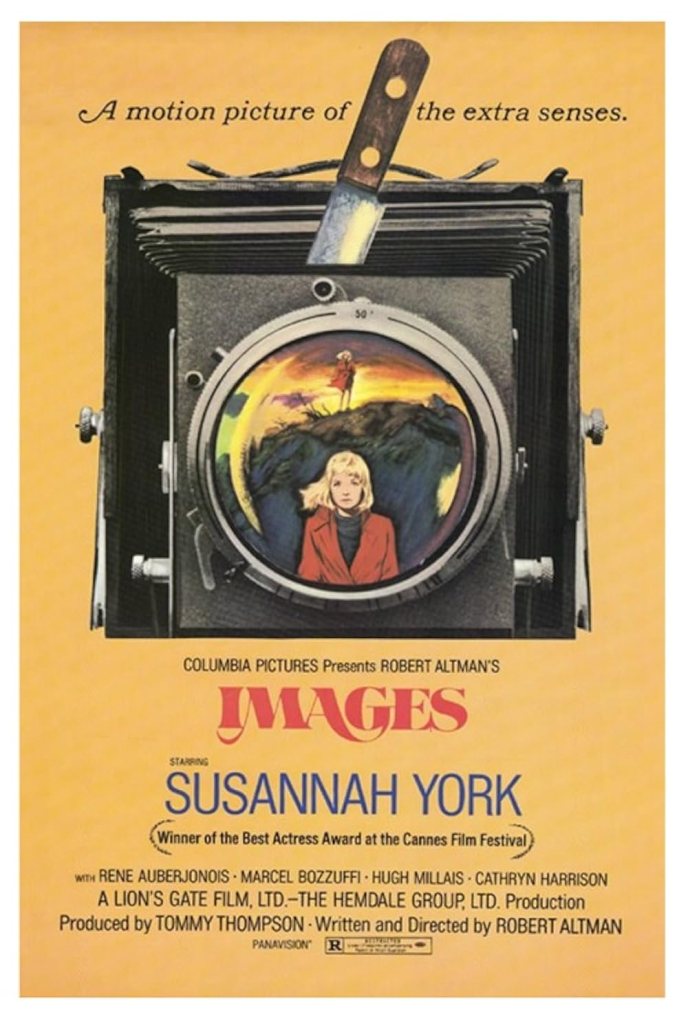

Film Details

Year: 1972

Studio: Lion’s Gate Film, Ltd./The Hemdale Group, Ltd.

Director/Writer: Robert Altman

Producer: Tommy Thompson

Main Cast: Susannah York, Rene Auberjonois, Marcel Bozzuffi, Hugh Millais, Cathryn Harrison, John Morley

Genre: Drama – Mystery

For synopsis and full cast and crew credits, visit the IMDb page

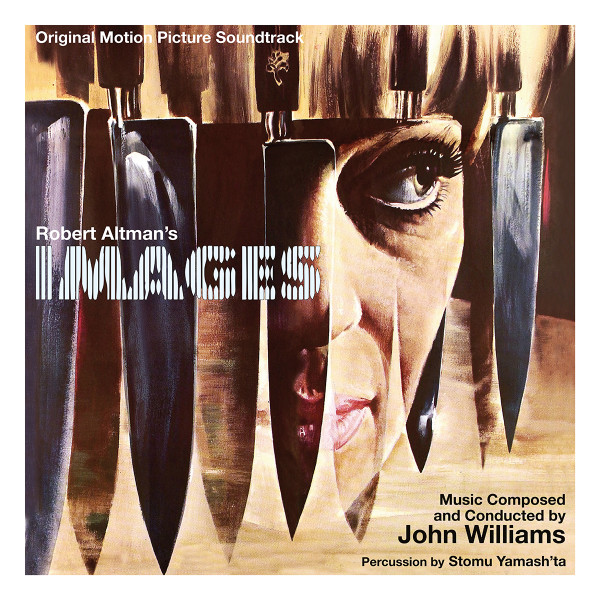

Music Credits

Music Composed and Conducted by John Williams

Percussion by Stomu Yamash’ta

Scoring Mixer: John Richards

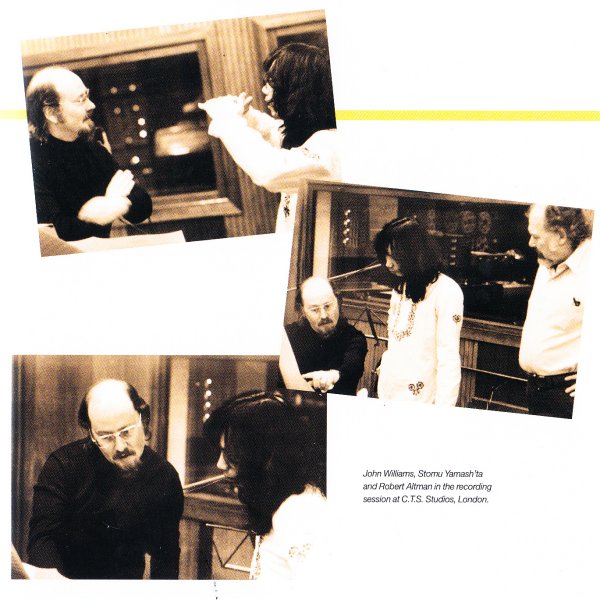

Recorded at C.T.S. Studios, Bayswater, London, United Kingdom

Recording Dates: February 16-17 and March 14, 1972

Essential Discography

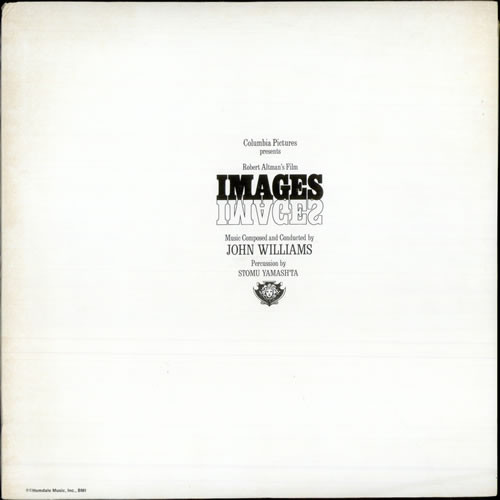

Music From Robert Altman’s Film “Images” – Promo LP (1972)

Hemdale Music, Inc. – No catalog number

Produced by John Williams

Limited vinyl pressing of the unreleased original soundtrack album program

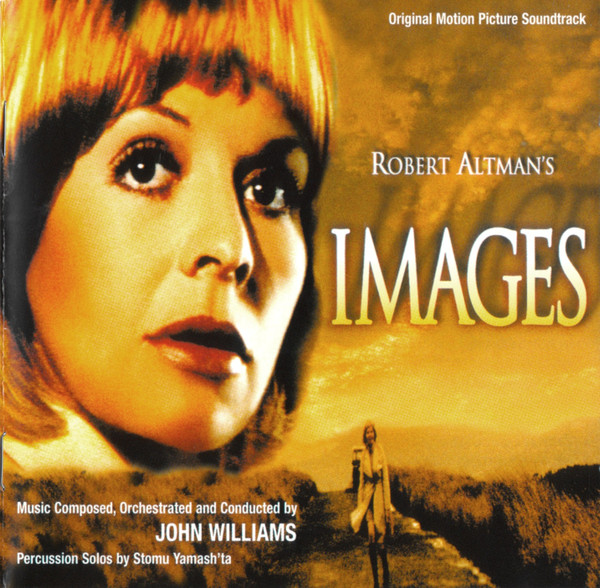

Original Motion Picture Soundtrack – CD (2007)

Prometheus Records LPCD 163

Supervised for release by Ford A. Thaxton

Digital Mastering: James Nelsons

Liner notes: Jon Burlingame

First official CD release of the planned original 1972 soundtrack album

Original Motion Picture Soundtrack – CD Reissue (2021)

Quartet Records – QR455

Album Produced by John Williams

Reissue Produced and Mastered by Mike Matessino

Liner notes: Jon Burlingame

Remastered reissue of the planned original 1972 soundtrack album; also available as vinyl (QRLP20)

Selected Re-recordings

John Williams Reimagined (2024)

Warner Classics – 5054197942334

contains “In Search of the Unicorns” from Images, arranged for piano and flute by Simone Pedroni

Sara Andon, flute

Simone Pedroni, piano

Awards and Nominations

1973 Academy Awards

Nomination: Best Original Dramatic Score

In Williams’ Words

“In his new film Images, Robert Altman creates Umbany, the strange “other” world in the life of Cathryn, his female protagonist. In photographing the film, Altman shows a corner of Ireland to achieve the alone-ness, the never-before-seen strangeness of Umbany. The film, however, does not seek to contrast the two worlds of the schizophrenic Cathryn. Instead, it creates an atmosphere so conducive to Cathryn’s flights from reality that, during the course of the film, the audience becomes unable to distinguish between fact and fantasy – for Altman, with consummate skill, withholds this distinction from the audience until the final moments of the film.

When Altman first showed me his film in London in January of 1972, I was overwhelmed by the picture and the atmosphere he created. It did seem to me, however, that some contrast between the “real” and the “unreal” might be achieved musically – not for the purpose of cueing the audience, but more to get inside of Cathryn’s head, so to speak, and musically accompany her state of mind rather than her physical condition or behavior. I wanted to contrast the sad, loveless, childless greyness of her “real” life with the terrifying encounters of her “other” existence. For her real-life music I composed a simple, sad, G-minor tune, but with peculiar Prokofiev-like shiftings of key center, and contrasted with a 6/8 running-in-the-woods kind of figure. All of this is presented in a very conventional way, set for piano and string orchestra, without giving any hint of the horrors Cathryn is to experience. I also tried to give this “real” music a quality of great age so that it would accompany Cathryn as she composed her stories for children, which seemed to be made up of characters from an epoch long forgotten.

While searching for an idea for the music of Cathryn’s “other” life, I remembered a concert presentation given in Los Angeles some years ago. The concert featured music performed on sculptures created in Paris by the French sculptors François and Bernard Baschet. I remembered the sculptures being visually striking, and the possibilities for the sounds created on these instruments were unmistakable. A few years after this concert, while on a trip to London, my friend André Previn brought the work of a Japanese percussionist, Stomu Yamash’ta, to my attention, and mentioned to me that Yamash’ta was performing music on the sculptures of Baschet. The memories I had of the sculptures, with the coincidence of Yamash’ta’s performance in London, did not come together in my mind until I was suddenly struck with the idea that these elements were exactly what I needed for Altman’s film.

I immediately contacted Yamash’ta who was instantly receptive to the idea, and we met in Paris, where he lives, to discuss how I could work out a practical method of notation for the Baschet instruments. This was not difficult, since Yamash’ta is a superb musician and was instantly able to play with total accuracy anything I notated for him, including the various vocal noises and more conventional percussion effects that appeared in the score.

Combined with string orchestra and keyboards, Yamash’ta’s playing served to accompany Cathryn’s flight from reality. It accompanies her meetings with lovers past and present, and underscores her three acts of violence, two imagined and one real.

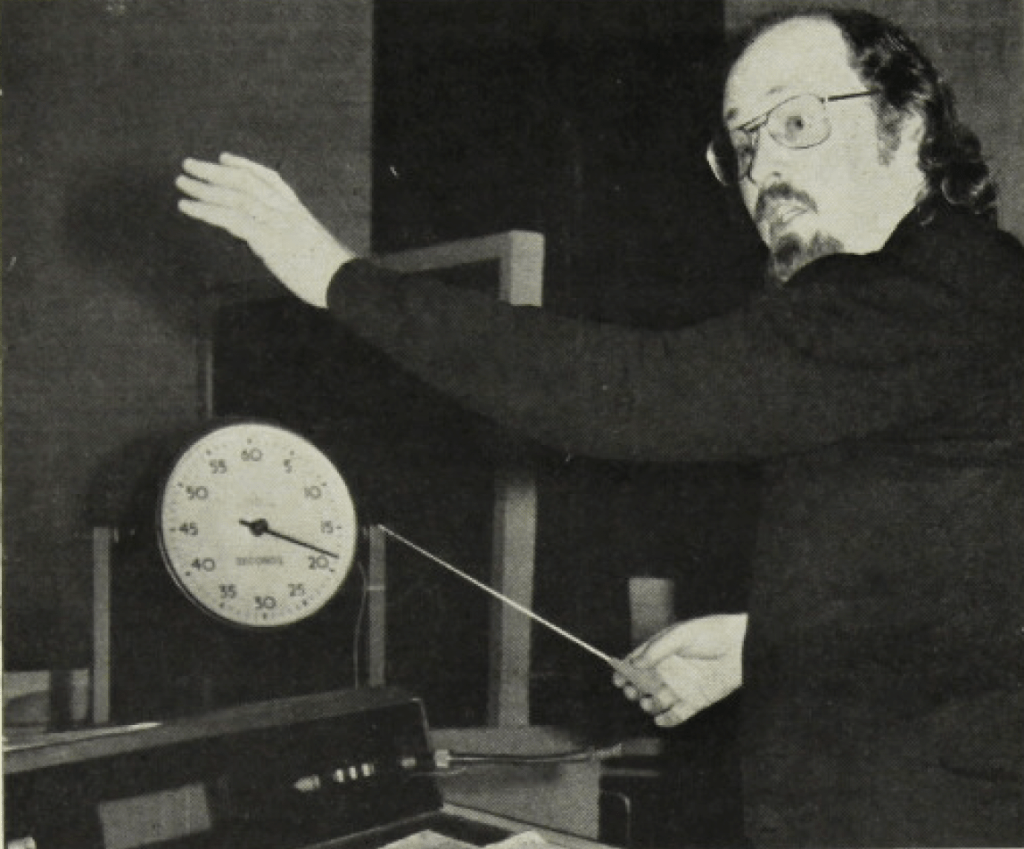

In writing this music I employed some of the current methods of the avant-garde, that is to say, graph-like music without the use of bar lines, etc., producing some random aleatory-like freedom but within the rigid discipline of split-second timing when the film’s action required it. This music is written for a normal string orchestra of approximately 26 players, with all vocal and percussion effects done by Yamash’ta, and all keyboard playing done by myself. Also, Yamash’ta’s own creative contribution was invaluable, especially his performance on shakuhachi, the traditional Japanese flute, as well as other percussion effects of his own invention, all of which he lent freely to the enterprise.

I also want particularly to thank John Richards of C.T.S. Recording Studios in London for his marvelous work in the recording of the music.” 1

“I wanted to use all textures and strings and nothing else – the only thing added would be Stomu’s voice. He does it in his concerts of some of [Hans Werner] Henze’s pieces. So it was the Japanese style of the percussion, the resonance of the instruments, and his chest – he might even say “ouch” in Japanese.

What I have on the score is just an aural noise, so his voice is a contribution. So there is, in fact, an immense creative contribution, because his performance is outstanding, I think, and deserving of every credit he has. I don’t want to detract from Stomu’s participation, but I felt very strongly that we have the discipline of the written symbol, timed to the film in its dramatic application, and that, I think, is what gives it its unique sense, rather than haphazardness, of taut discipline.

So I reckoned percussion, keyboards – which I wanted to play all myself – and string orchestra. We began by recording – I wrote the score in the normal way – the string orchestra here, the keyboards here, and the percussion here. And the keyboards – I might play a particular section piano or piano twice, banging here, improvising something here, or playing something written here. The keyboard might be on three lines, which would require – since I was going to play it all – three overdubs on the piano; the percussion is almost always four or five lines.

You would hear Japanese woodblocks, you would hear Baschet-sculpture percussion, you might hear timpani, etc., in one sequence. My idea was to make the most personal, idiosyncratic thing, have one man play everything, rather than have four percussionists, which I could have done – let Stomu play everything.

So the first thing I did was recording the string orchestra for a whole day – all the traditional music, all of this material, and to time it exactly when the legitimate orchestra stopped and Stomu and I started with either our written notes or whatever we were going to do. And then we would select one, i.e., the woodblocks and the piano first. It was done on sixteen-track tapes, so we put the string orchestra left, center, and right; that left me thirteen tracks of tape to play around with. And we proceeded in that way. Stomu would take line one and play that, then line two, putting on the earphones to hear what he just recording on line one. Then on line three he heard lines one and two back. And I drew on the score – where, if you play pa pa, I play ta tee; I’m taking my notes from your cue. In this case he would just follow the arrows, which are indicated on the percussion production notes. And he followed himself with his own timings and made a wonderful effect.” 2

“Years ago, I did a film called Images for Robert Altman, and the score used all kinds of effects for piano, percussion, and strings. It had a debt to [Edgar] Varèse, whose music enormously interested me. If I had never written film scores, if I had proceeded writing concert music, it might have been in this vein. I think I would have enjoyed it. I might even have been fairly good at it. But my path didn’t go that way.” 3

Quotes and Commentary

John Williams had scored a lot of the television work that I did at Universal when he first started doing scores. He was a personal friend. I talked to him about doing Images from the very beginning and I said, ‘Here’s an idea: I want you to read the script, tell you about and answer any questions about what I think this film is gonna be like, then you score it before I shoot it. You score it and record it, and then I’ll shoot my picture and use your score.’ Now, we didn’t exactly do that, but I do that and did ever since—I’m not much interested in a score that goes right along with the action. So we talked about that approach and then John came up with Stomu Yamash’ta, who is a percussionist and he had an act—he would go out and do performances where he would play all these weird sounds along with the band. I remember we had an old piano carcass, and he would throw a rock into it, onto the strings and onto the sounding board, and it went boooom. But John Williams wrote those into the score, specifically, and what they were. The score itself I have framed, and it’s just a gorgeous, it should be in a book, because you see this, in the staffs… suddenly it’ll say, ‘Hiss like an angry snake’ or he’ll have these kind of sound descriptions Stomu would perform.4

– Robert Altman

In early 1972, composer John Williams embarked on his most daring score: the music for Robert Altman’s film Images, starring Susannah York. The film, about a schizophrenic woman whose loosening grip on reality may be taking murderous turns, would ultimately win York a best-actress prize at the Cannes Film Festival – and, for Williams, his fifth Academy Award nomination.

Images is Williams’ avant-garde masterpiece – written, for the most part, for strings, piano and percussion – with keyboards played by the composer himself and the percussion entirely the work of Japanese artist Stomu Yamash’ta. Yamash’ta, then just 24, had already gained a reputation as one of the world’s most talented young percussionists.

This was the first of two feature-film collaborations between the celebrated director of M*A*S*H and the composer (The Long Goodbye, another offbeat score, would follow in 1973), but it was far from their first meeting. They had known each other for several years, dating back to Altman’s direction of Kraft Suspense Theatre episodes nine years earlier, when Williams was regularly scoring Universal television shows. They remained friends, and when Altman wrote the Images script in the late 1960s, he suggested to Williams, “you score it, and then I’ll shoot it.”

For reasons of scheduling, that didn’t work out. But Altman – who was always interested in unorthodox filmmaking techniques – wanted Williams to have as much freedom as possible. […]

Since Altman’s script concerns an increasingly unbalanced woman named Cathryn who has trouble distinguishing between reality and illusion, Williams decided to take a similarly dual-minded approach. When she is mostly in the real world, writing her children’s book, the score is conventional, even lyrical, relying mostly on piano and strings. But when Cathryn begins to imagine things – seeing a former lover whom she knows to be dead, talking with a mirror image of herself, resisting the romantic overtures of a husband’s friend, and attempting to kill all of them – the music takes a radical turn, utilizing non-tonal percussion in the wildest ways possible, from eerie atmospheric sounds to crashing dissonance.5

-Jon Burlingame

Videos

Director Robert Altman and cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond on Images | DVD bonus feature | Produced and Directed by Greg Carson | 2003

Images Original Theatrical Trailer (featuring music by John Williams)

Brett Mitchell performs his original piano arrangement of “In Search of the Unicorns” from Images

Bibliography and References

. Bazelon, Irwin – Knowing The Score – Notes On Film Music, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1975

. Brown, Royal S. – Overtones and Undertones – Reading Film Music, University of California Press, 1994

. Burlingame, Jon – Images – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack liner notes, Quartet Records QR455, 2021

. Dyer, Richard – “Where is John Williams coming from?,” The Boston Globe, June 29, 1980

. Palmer, Christopher – “Composer John Williams: A Profile,” Crescendo Music International, April 1972

. Ross, Alex – “The Force Is Still Strong With John Williams,” The New Yorker, July 21, 2020

. Sherwood Magee, Gayle – Robert Altman’s Soundtracks: Film, Music, and Sound from M*A*S*H to A Prairie Home Companion, Oxford University Press, 2014

Footnotes

- Unpublished original album notes, printed for the first time on Images – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Quartet Records, 2021 ↩︎

- Quoted in Bazelon, Knowing The Score, 1975 ↩︎

- Quoted in Ross, The New Yorker, 2020 ↩︎

- Images DVD bonus feature, MGM Home Entertainment, 2003 ↩︎

- Burlingame, Images – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack liner notes, Prometheus Records, 2007 ↩︎