Table Of Contents

- Film Details

- Music Credits

- Essential Discography

- Awards and Nominations

- In Williams’ Words

- Quotes and Commentary

- Videos

- Bibliography and References

Film Details

Year: 1973

Studio: United Artists/APJAC International

Director: Don Taylor

Writers: Robert B. Sherman, Richard M. Sherman, based on the novel by Mark Twain

Producer: Arthur P. Jacobs

Main Cast: Johnny Whitaker, Celeste Holm, Jeff East, Warren Oates, Jodie Foster, Lucille Benson, Henry Jones, Noah Keen

Genre: Adventure – Musical

For synopsis and full cast and crew credits, visit the IMDb page

Music Credits

Music & Lyrics by Richard M. Sherman & Robert B. Sherman

Music Conducted and Adapted by John Williams

Music Editor: Kenneth Wannberg

Music Recordists: Murray Spivak, Vinton Vernon

Concertmaster: Louis Kaufman

Recorded at 20th Century Fox Scoring Stage, Hollywood, California

Recording Dates: June 19, 21, 27, 28; July 19, 27; December 27, 1972; January 25 and 26, 1973

Essential Discography

Original Soundtrack Album and Expanded Reissues

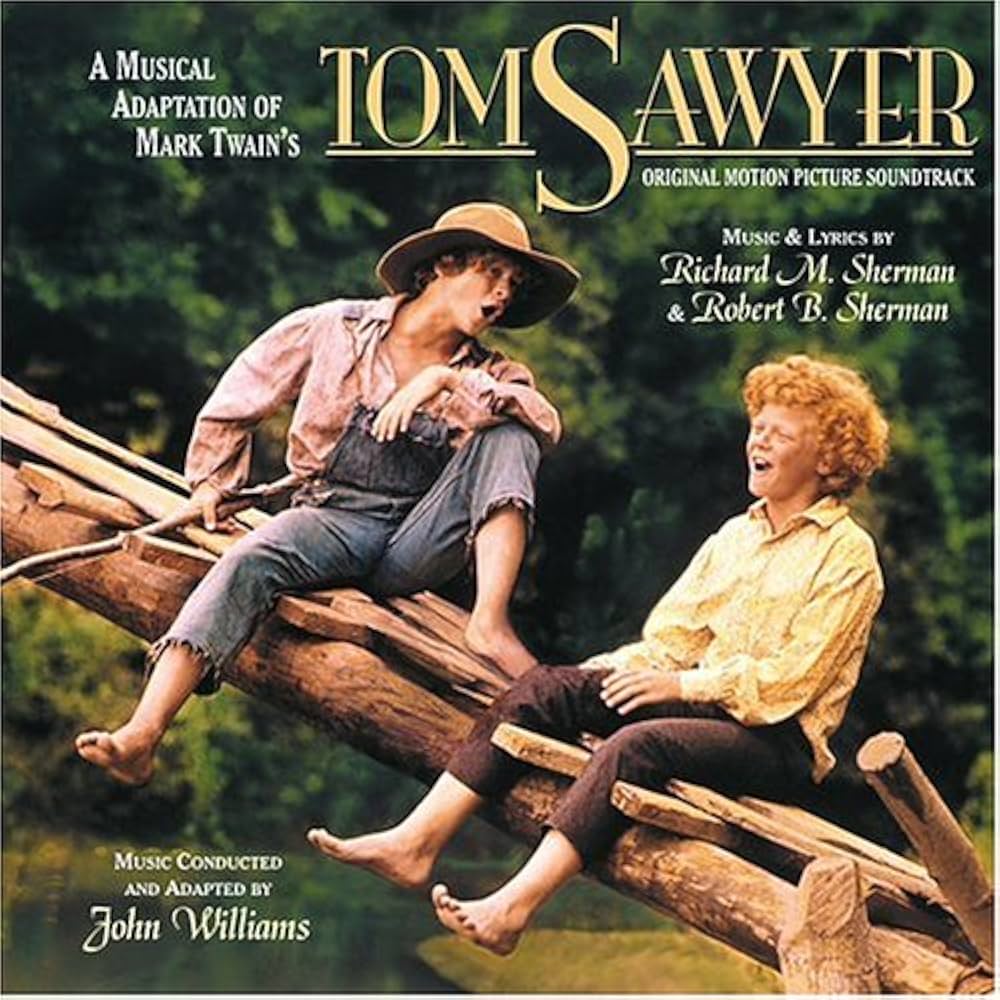

Original Motion Picture Soundtrack – LP (1973)

United Artists Records – UA-LA057-F

Original Motion Picture Soundtrack – CD Reissue (2004)

Varèse Sarabande 302 066 601 2

Executive Producer: Robert Townson

Mastered by Erik Labson

Liner notes: Jerry McCulley

First CD reissue of the 1973 original soundtrack album; also contains the film soundtrack of Huckleberry Finn (1974) by Fred Werner

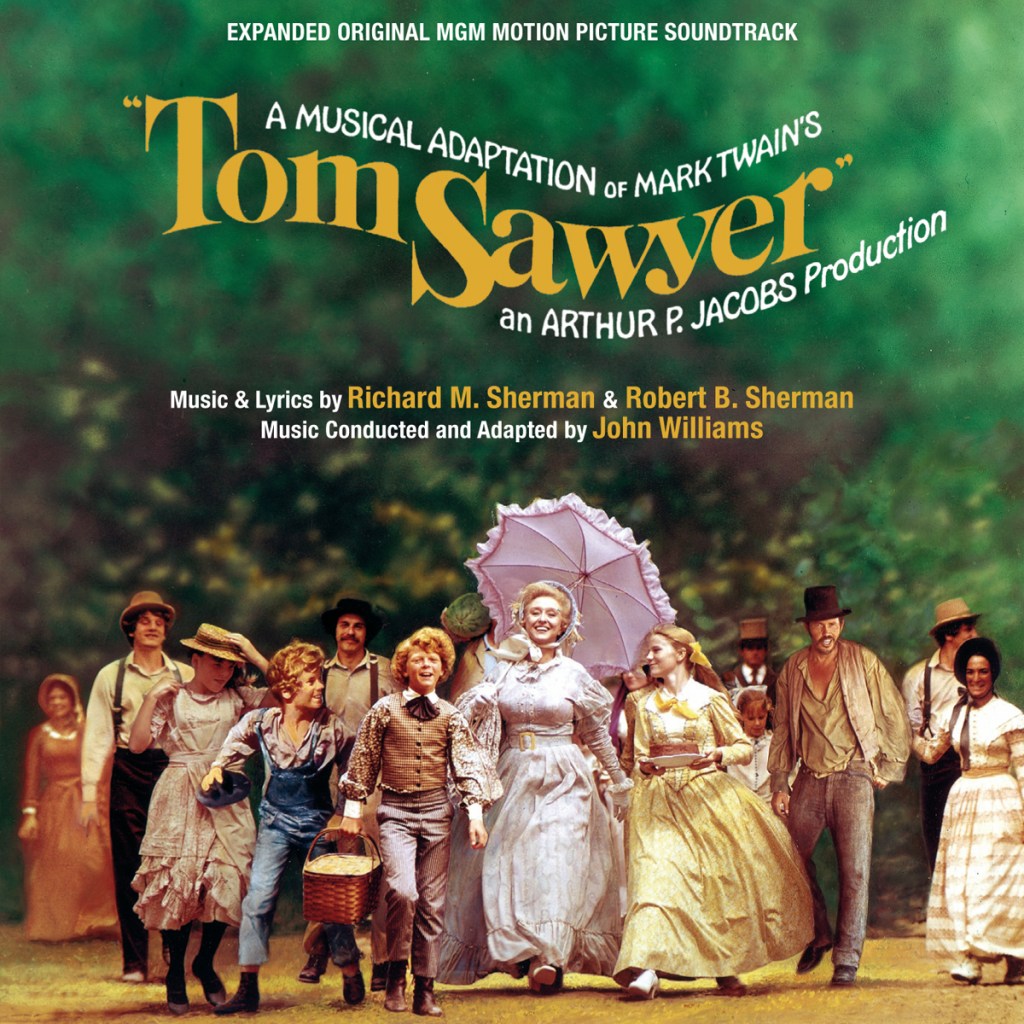

Expanded Original Motion Picture Soundtrack – 2-CD Reissue (2015)

Quartet Records – QR211

Produced by Josè M. Benitez

Remixed and Edited by Josè Vinader

Mastered by Doug Schwartz

Liner notes: John Takis

Remastered reissue of the original 1973 soundtrack album, plus instrumental versions of the songs on Disc 1; expanded film score presentation (in mono sound) on Disc 2

Awards and Nominations

1974 Academy Awards

Nomination: Best Original Song Score and Adaption, or Scoring: Adaptation

1974 Golden Globe Awards

Nomination: Best Original Score

In Williams’ Words

“Whatever hierarch types there may be that criticize popular songwriting

at every level, whether it’s Irving Berlin or the Sherman Brothers, who will criticize the idiom, will be critical of composers in a wide range that do this work. But I think there’s a ground that’s higher than what professionals recognize, and that is that if you get high enough in any kind of work — good enough, put it that way — the issue of style becomes unimportant. You get beyond that.”1

Quotes and Commentary

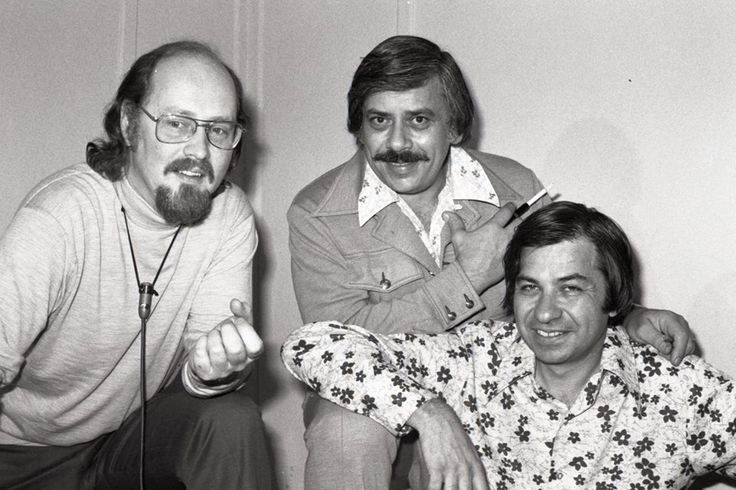

John Williams is a hero. He’s so great. He made everything smooth and just perfect… A great scoring man, when he’s working with a musical, will take the songwriter’s work and compose with it, and make it work for the film. So he would be composing with our themes, and doing wonder — bending and switching and fiddling around. It was a wonderful, masterful piece of work.2

– Richard Sherman

The Shermans — composer Richard M. and lyricist Robert B., known intormally as Dick and Bob hardly came by their musical prowess by accident. The sons of veteran songwriter A.J. Sherman (who’d written songs for Eddie Cantor, Maurice Chevalier and others) attended Beverly Hills High School and New York’s Bard College (where, a decade later, Steely Dan’s Walter Fagen and Walter Becker would forge their own considerable partnership), their studies echoing their later division of labor: the younger Richard majored in music, elder brother Robert in English. Teaming as songwriters in the early ’50s, the pair’s work was recorded by Kitty Wells, Doris Day and Fabian before Annette Funicello’s novelty hits “Tall Paul” and

“Pineapple Princess” gained them some fame.

The novelty nature of their work and the association with Funicello led to Disney, where they wrote “The Strummin’ Song” for the 1961 TV production The Horsemasters. A meeting with Walt Disney himself about another project led them to a high-profile participation in the hit The Parent Trap. Their successes at the studio quickly mushroomed thereafter.

But their creative relationship with the studio became more problematic after the death of Walt Disney, and they began to expand their professional hurizons with projects like UA’s Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and Paramount’s animated adaptation of Charlotte’s Web.

Their 1973 musical take on Tom Sawyer had a long gestation, having previously been in development at Warner-7 Arts (where one strange possibility had it being shot on location in Europe) and as a joint venture between Cinerama and Freeman-DePate-Freleng.

The project ultimately came to be produced by former agent Arthur P. Jacobs, backed by UA and Reader’s Digest in a pioneering financial arrangement. It also marked an elevated level of creative input from the Sherman’s, who also penned its screenplay. Composer John Williams, who’d recently scored his first Oscar for the screen adaptation of Fiddler on the Roof, collaborated extensively with the brothers in a similar capacity, gaining the trio an Academy Award nomination for their work. Country star Charley Pride was given a spotlight turn on the graceful, melancholy “River Song” that bookends the film and helps set its tone.3

-Jerry McCulley

Through a string of sixties and seventies scores that included The Reivers, The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing and The Sugarland Express, John Williams left no doubt about his fluency in the vernacular of American folk music. This made him an ideal collaborator on Tom Sawyer, where his arrangements drew on ragtime and Dixieland jazz, and embraced the colors of harmonica, guitar and piano. He was also an expert at navigating tonal shifts, pivoting gracefully from the boozy exuberance of “A Man’s Gotta Be” to the sweeping emotion of “How Come?” to the introspective poetry of “If’n I Was God.”

Williams composed a vivacious overture and finale using the Shermans’ themes. Other than these two pieces, and some interstitial material within the songs, the only underscore to appear on the film’s original soundtrack assembly was the main title.

As the opening credits roll, the opening lick from “Tom Sawyer!” appears in harmonica, then brass, interweaving with strains of “How Come?” and hints of “Hannibal, Mo-(Zouree)!” over a bustling string accompaniment. The score builds powerfully until the film’s stunning aerial reveal of the Mississippi river, at which point the chorus breaks into “River Song.”

When it came to the film’s incidental music, the brothers were happy to give Williams wide latitude.

“T’d say that John was pretty much his own master,” Richard Sherman says. “Once in a while we’d talk about it: ‘How about if we just interpolate a little bit of…’ “Yeah, we can do that! But it was his score.” Similarly, the Shermans took a back seat at the recording sessions. “We went to everything, overlooking and overseeing, hearing things. And we’d do some adjustments. But basically, it was John’s show.”

The element of the film where Williams was most able to be himself was the Injun Joe storyline-in particular, the graveyard murder of Doc Robinson and the final confrontation with Joe in McDougal’s Cave. Rife with dissonance, turbulent strings and eerie wandering lines for brass and flute, it is easy to hear in these cues the composer who was on the cusp of writing The Towering Inferno and Jaws. Interestingly, the cue for when Tom and Huck engage in their most extreme act of piratical behavior — pricking their thumbs to solemnify a midnight pact in “Sworn in Blood” — strongly foreshadows Williams’ score for Hook, composed almost two decades later.4

– John Takis

Videos

“Main Title and ‘The River Song’” from Tom Sawyer

“Gratifaction” scene from Tom Sawyer

“If’n I Was God” scene from Tom Sawyer

“Freebootin’” scene from Tom Sawyer

Bibliography and References

. McCulley, Jerry – Tom Saywer – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack liner notes, Varèse Sarabande, 2004

. Price, Kathryn M. – Walt Disney’s Melody Makers: A Biography of the Sherman Brothers, Theme Park Press, 2018

. Takis, John – Tom Saywer – Expanded Original Motion Picture Soundtrack liner notes, Quartet Records, 2015

Legacy of John Williams Additional References

John Williams and The American Sound, essay by Maurizio Caschetto

Footnotes