Before John Williams believed in himself as a conductor, the general manager of the Los Angeles Philharmonic believed in him.

Ernest Fleischmann was a savvy and powerful impresario, born in Germany in 1924, raised in South Africa to escape the Nazis, a frustrated conductor and journalist who managed the London Symphony Orchestra for eight years and ran the European classical division of CBS Records before coming to Los Angeles in 1969 and transforming a “provincial second-rank orchestra,” as L.A. Times critic Mark Swed wrote, “into one of the world’s best.”

Equally loved and despised, Fleischmann was once called the “P.T. Barnum of orchestra managers,” an outsized personality who shaped the classical scene in Los Angeles for three decades with a keen eye for talent, passion for a good show, and little concern for the artificial barriers between “high” and “low.” He loved the ancient repertoire and new music alike—and he was one of the first American gatekeepers of classical music to open the gates to film music in a significant way.

When Fleischmann saw Star Wars with his kids on opening weekend in the summer of 1977, he thought to himself: God, this score! “It’s really the score and the sound effects that have made that movie what it was,” he later said. “It was almost Wagnerian.” The LA Phil was scheduled to tour Japan that fall, but the tour was canceled at the last minute when the promoter went bankrupt. With his orchestra suddenly freed up, and Star Wars totally consuming the culture, Fleischmann saw a plum opportunity; he paid a visit to John Williams’ Brentwood home and asked the composer if the LA Phil could perform music from Star Wars in a concert of space-themed music. Williams said “Fantastic,” and created a special 28-minute suite from his already super-famous, record-breaking score.

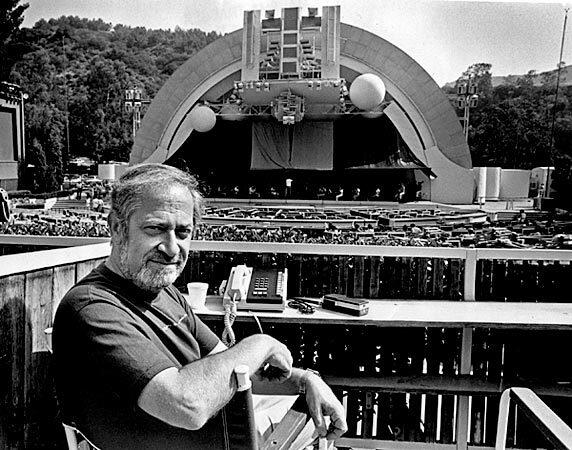

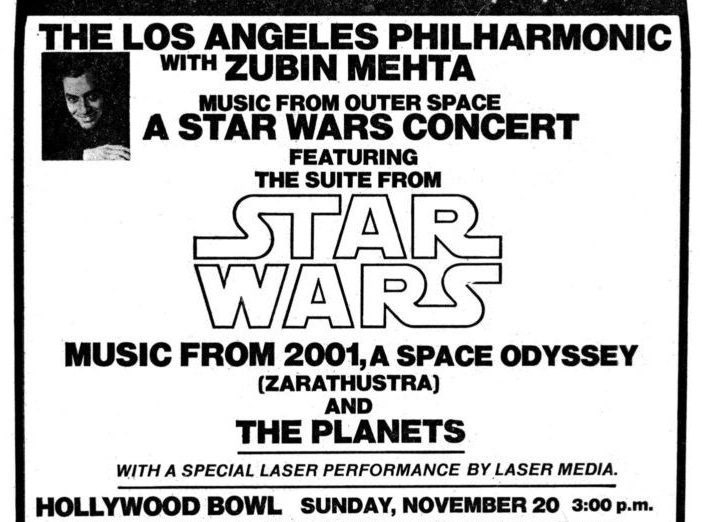

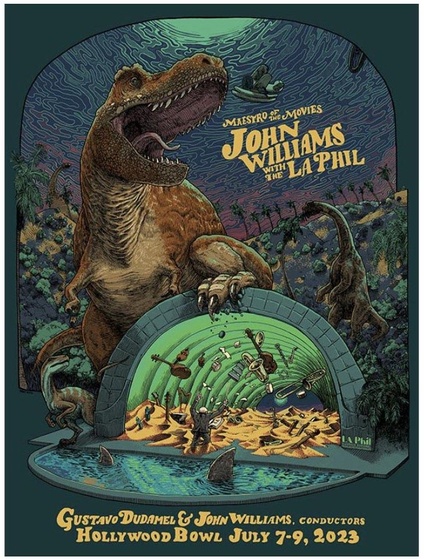

The resulting concert on November 20th, 1977 at the Hollywood Bowl—the iconic outdoor summer home of the LA Phil—was a galactic party designed for young families, complete with a laser light show and readings by William Shatner. The sold-out audience went crazy for it, but the event also highlighted the deep tension between anointed priests of “high culture” and the hoi polloi. “We were criticized very heavily,” recalled Zubin Mehta, the LA Phil’s music director who conducted that night. “Our critics and colleagues said that we had sold our souls to Hollywood. It was really a children’s concert.” The grumpy L.A. Times critic Martin Bernheimer called it “artistic prostitution.”

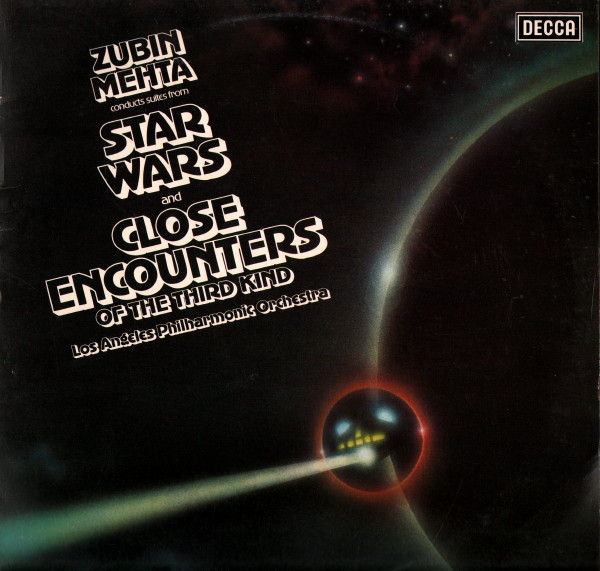

Fleischmann didn’t care. He had the LA Phil repeat the “Music from Outer Space” program at the California Angels’ baseball stadium in nearby Anaheim, and he commissioned an album of the Star Wars suite and Williams’ new Close Encounters suite, recorded at UCLA’s Royce Hall in December 1977 by Mehta and the orchestra. According to veteran classical music broadcaster Jim Svejda, it was the first time a major American orchestra treated film music “in a very serious way. I think it made a very dramatic statement.”

“I told Zubin I couldn’t understand it,” Williams said in 1980. “I have no pretensions about that score, which I wrote for what I thought was a children’s movie. All of us who worked on Star Wars thought it would be a great Saturday morning show. We had no idea it was going to become a great world success.” Star Wars music was performed in an estimated four hundred concerts during the season of 1978–79… and it never stopped being performed.

The following summer, Fleischmann asked Williams to conduct a concert himself. “You look like a veteran,” Fleischmann told him. “Just go do it.” Williams demurred: “I’m not a conductor, Ernest!” “Yes you are,” Fleischmann insisted.

Williams had plenty of conducting experience, of course, beginning with his four years in the Air Force band division. (With his typical self-deprecation, he maintained this wasn’t conducting but simply “counting measures.”) For two decades he had been conducting countless orchestra dates in the studio, both on pop records and on his many scores for television and films. (The great conductor Leonard Slatkin said that his father, Felix Slatkin, gave John some baton instruction.) He had conducted at Academy Awards ceremonies, and now he had even conducted the London Symphony Orchestra. Public concerts were a different beast, though, and they required a different mindset and mode. Williams stressed that he had no real desire to conduct public performances. “I don’t concertize,” he wrote in a 1976 letter to an admirer—“it’s just not part of what I do professionally, whereas Mancini and Elmer Bernstein and Michel Legrand and some of these other chaps do that as a way of earning money.”

But he had conducted concerts on a few occasions, and as early as 1969 he told his close friend André Previn that he had the “predictable itch to do a little conducting.” On September 16th, 1972, in what may have been his public debut, he led the Burbank Symphony in selections from his latest scores from Fiddler on the Roof, Images, and The Cowboys at the local Starlight Bowl. In April 1974, just six weeks after the sudden death of his wife, Barbara, he conducted the Glendale Symphony in his flute concerto. As his star was beginning to ascend, in November 1976 Williams accepted an invitation to participate in the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra’s “Filmharmonic” night, where he conducted a robust sampling of his recent triumphs, from Fiddler and The Poseidon Adventure to his recent blockbuster score for Jaws. Then, in his most prominent appearance yet, he reunited with the LSO in February 1978 to conduct music from Star Wars and other space movies at the Royal Albert Hall.

But he had no formal training and very little confidence in his ability on the podium with a symphony orchestra and a paying audience.

It was Ernest Fleischmann who pressed him into service when, in the summer of 1978, Arthur Fiedler fell ill and could not make his scheduled dates with the LA Phil at the Hollywood Bowl. Williams was in London when he got the call, in the midst of recording his score for Superman, and he agreed to fly back to L.A. to conduct concerts on July 28th and 29th—taking Fiedler’s planned program (which included a Mozart horn concerto, Berlioz, and Ralph Vaughan Williams) and adding to it his concert overture from The Cowboys, music from Fiddler, and—naturally—Star Wars.

These hodgepodge concerts were a somewhat awkwardly arranged marriage, and the L.A. Times reviewer was not kind: after calling Williams’ own music “baldly derivative,” Lewis Segal criticized Williams’ conducting as “flat and dutiful,” and called out his inability to distinguish between the different classical pieces: “These faceless, note-by-note performances also made repeats identical to initial statements, ignored opportunities for dynamic variety and displayed no sense of rhythmic elasticity or even forward momentum.” It would be the first in a long line of venomous reviews from the hometown clergy of orchestral music.

But Williams had overcome some of his own self-doubt, and he gladly accepted a few guest conducting invitations with the Boston Pops shortly afterward. The classical world was stunned when he was offered the Pops directorship in 1980; he was an utterly left-field choice for the position, and it was equally baffling why an incredibly busy and successful film composer would want the job. He gave several reasons at the time: he wanted to steep himself in classical repertoire; he thought a summer of concerts, with one of the premier orchestras in the world, would reinvigorate his composing; and he hoped he might be able to record some of his scores with the Boston orchestra. (He recently admitted that he took the job because Previn “wanted me to be a conductor. And André wanted me to leave Hollywood.”)

It was another slightly awkward marriage at first, and a few musicians and some classical snobs gave him a side-eye. His actual conducting style rarely earned much praise. But over time he grew in his ease on stage and his skill as a performer, and he slowly—with a little turbulence early on—reshaped that orchestra in his crowd-pleasing but ever dignified image; he became a beloved institution both at Symphony Hall and the Boston Symphony’s summer retreat at Tanglewood, taking the Pops on incredibly successful tours across the U.S. and around Japan, becoming friends with classical giants like Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa, writing and premiering beautifully complex concertos that sounded shockingly different from his well-known film scores, and growing in stature as a “classical” composer as he simultaneously elevated the reputation of film music—an unprecedented achievement that recently culminated in conducting invitations from the best orchestras in the world.

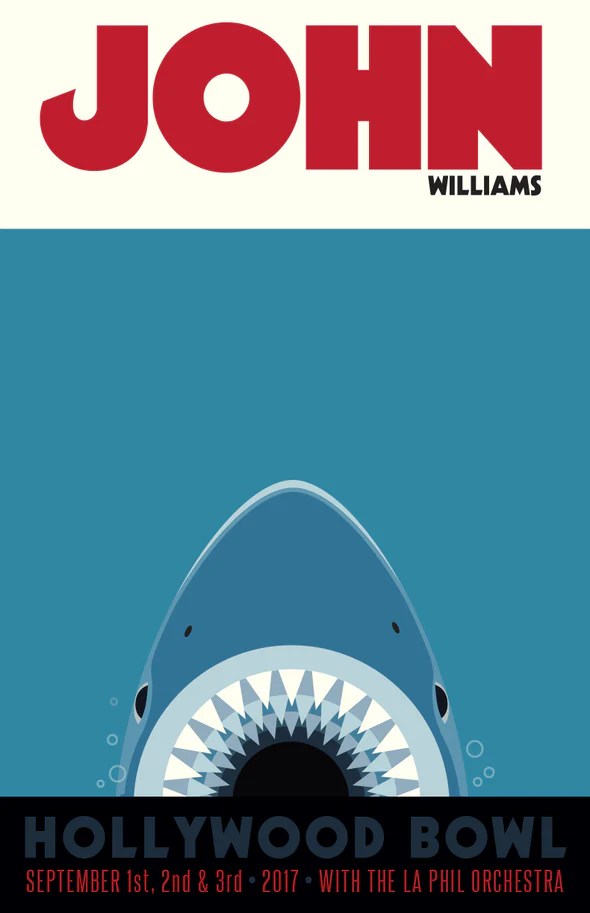

But it arguably all started at the Hollywood Bowl, with Ernest Fleischmann enthusiastically handing Williams the keys to the Los Angeles Philharmonic. “He was right about the Bowl,” Williams told me, “because that’s been a career. And that’s entirely Ernest’s insistence. I never would have done that.” The Bowl quickly became one of the primary sites where Williams shared and legitimized his film music, where he compellingly revealed what was initially considered low art to be some of the most widely beloved, deeply cherished, and universally uniting music composed in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Beginning in 1981, Williams became an annual fixture at the Bowl—a nearly unbroken chain of summers (sometimes with the LA Phil, sometimes with the Pops) where enormous crowds would gather under the stars, in this scenic amphitheater just off the 101 freeway, to listen to his popular themes. From the start audiences swarmed the place to hear Williams conduct his own music, consistently selling out the nearly 18,000-seat venue—even across three nights. “John Williams nights” became a favorite staple of summertime in Los Angeles, a yearly tradition for local families and out-of-town fans, and they only grew more successful as the years went by.

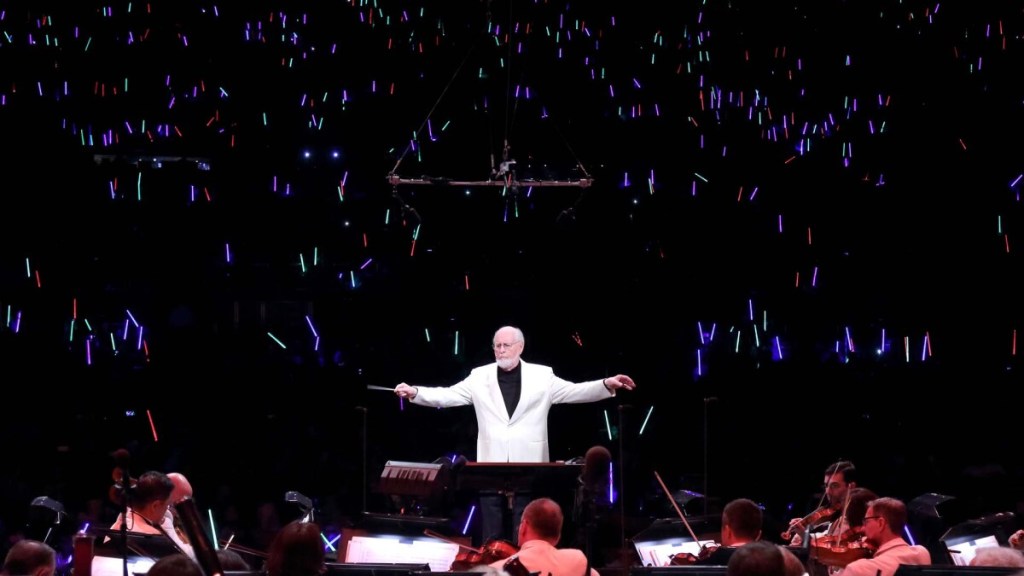

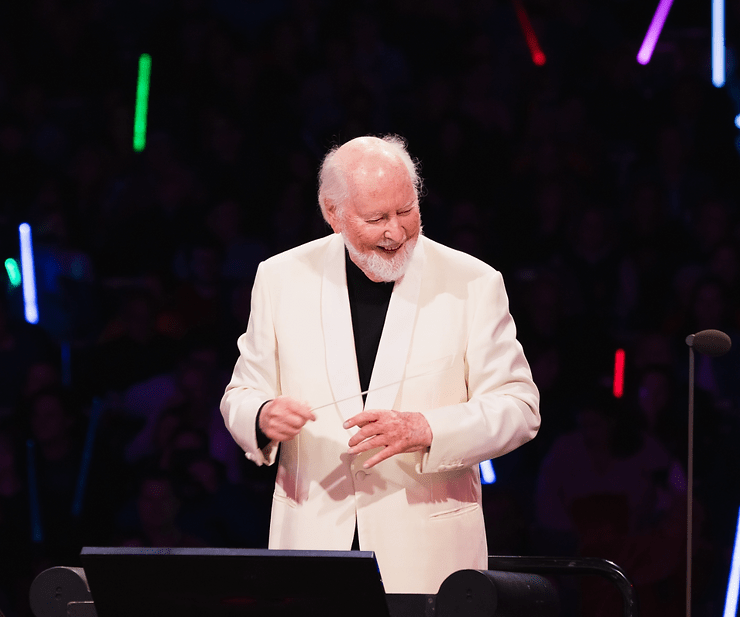

As Williams entered his seventh, eighth, ninth decade, there was no dwindling of concertgoers or passion. If anything, the zeal only intensified. In the last fifteen years it became a ritual for audience members to bring glowing toy lightsabers and wave them in time to selections from Star Wars; last summer Williams got in on the act himself with a “duel” onstage with his co-conductor, LA Phil music director Gustavo Dudamel (a friend and unabashed Williams fanboy). The electric energy in every audience—of all ages, genders, and colors—was the kind of thing one would expect to see at a Taylor Swift concert. Without fail, year after year, the Bowl filled to capacity with families and individuals who felt a profound emotional connection to the music of this unflashy, aging maestro, and they roared their love fortissimo.

The long chain that started in 1981 was only broken in 2015, when Williams was recovering from pacemaker surgery and also in the thick of scoring The Force Awakens, and then in 2020 when the Covid-19 pandemic canceled an entire year of concerts. Sadly, that chain was broken again this summer—one of several casualties of Williams’ (publicly unspecified) health issues. This weekend, David Newman will conduct all three concerts he had planned to share with his old master, which will include some of the music Williams wrote for various NBC television programs.

Williams’ cosmic rise in respect and stature as a conductor is unparalleled in the field of film composers; the only other Hollywood “cleffer” to forge such an impressive career on the podium was André Previn himself, but Previn did so almost exclusively with other peoples’ music. Williams did it with his own repertoire. And still, after nearly a half century of public conducting, from the Hollywood Bowl to the Musikverein, Williams insists the only reason he gets to concertize with these great orchestras is because of the music itself. “I used to conduct a lot of repertoire in Boston,” he said recently, “but now I conduct my own music. I leave the professional conducting to the professionals.”

Ultimately, it doesn’t really matter what he, or the critics, think of his conducting. When John Williams walks onto the stage anywhere—whether at the Bowl, or Carnegie Hall, or Suntory Hall in Tokyo—the place erupts. People came to see him, the legend, and to hear his music. He is more than a conductor… more than a composer. He has become a phenomenon.

Tim Greiving is an LA-based writer covering film and media music for the Los Angeles Times, NPR and The Washington Post. He is the author of the forthcoming biography of John Williams from Oxford University Press.