“Well this idea of hinting at themes that are to come, or suggesting and giving hints of themes we already know, was for me a new experience in this Phantom Menace… But I think it’s a thought that probably is going to emerge as a more important thought as we move on to the next couple episodes.”

John Williams, Promotional Interview for Star Wars: Episode I, 1999

Few movies in history arrived with so much musical hype as The Phantom Menace. In the fourteen years since Return of the Jedi, a vibrant subculture of soundtrack appreciation had emerged, much of which was concentrated in online forums and fanpages, places like the fondly remembered The Groovy Yak’s John Williams Message Board and the still-active Film Score Monthly and JWfan.com, the latter which began life as “Star Wars Episode I – The Music.” In those spaces, Episode I—this follow-up to a series that turned countless listeners on to the splendors of symphonic film scoring—was awaited with ecstatic fervor.

Granted, no one was expecting a score as paradigm-shifting as Star Wars 1977, nor as perfectly realized as Empire. But, given what the world would hear once that soundtrack was ~at last revealed~, the prospect of another trio of cine-symphonic masterpieces did feel at hand.

To avid listeners in 1999, The Phantom Menace‘s score did not disappoint. (The official soundtrack album, missing highlight after glorious highlight, was another matter…) Williams’s contribution was overflowing with invention on every page. It was sparkling and fresh in a way that more than compensated for a certain unevenness of musical argumentation—an unevenness mostly, but not solely, the product of the score’s anarchic editorial treatment in the film. And with 25 years of hindsight, it seems fair to say today that, yes, Episode I is worthy of that “masterpiece” label. But this score, along with the sequels that followed in 2002 and 2005, is a masterpiece in a more imperfect, more qualified way than its Original Trilogy precursors.

The biggest qualification for The Phantom Menace’s masterpiece-status does not involve merit as a standalone score. (Though for listeners expecting such opulently tuneful set-pieces as Empire‘s “The Asteroid Field,” Williams’s now more granular, motivicist approach to action scoring would take some getting used-to.) Rather, it is how the score fits within the rest of the series that warrants some critique. Episode I makes musical promises involving thematic developments to come in subsequent installments. But in retrospect, not all of these promises were delivered. At least, not in the Prequel film scores themselves…

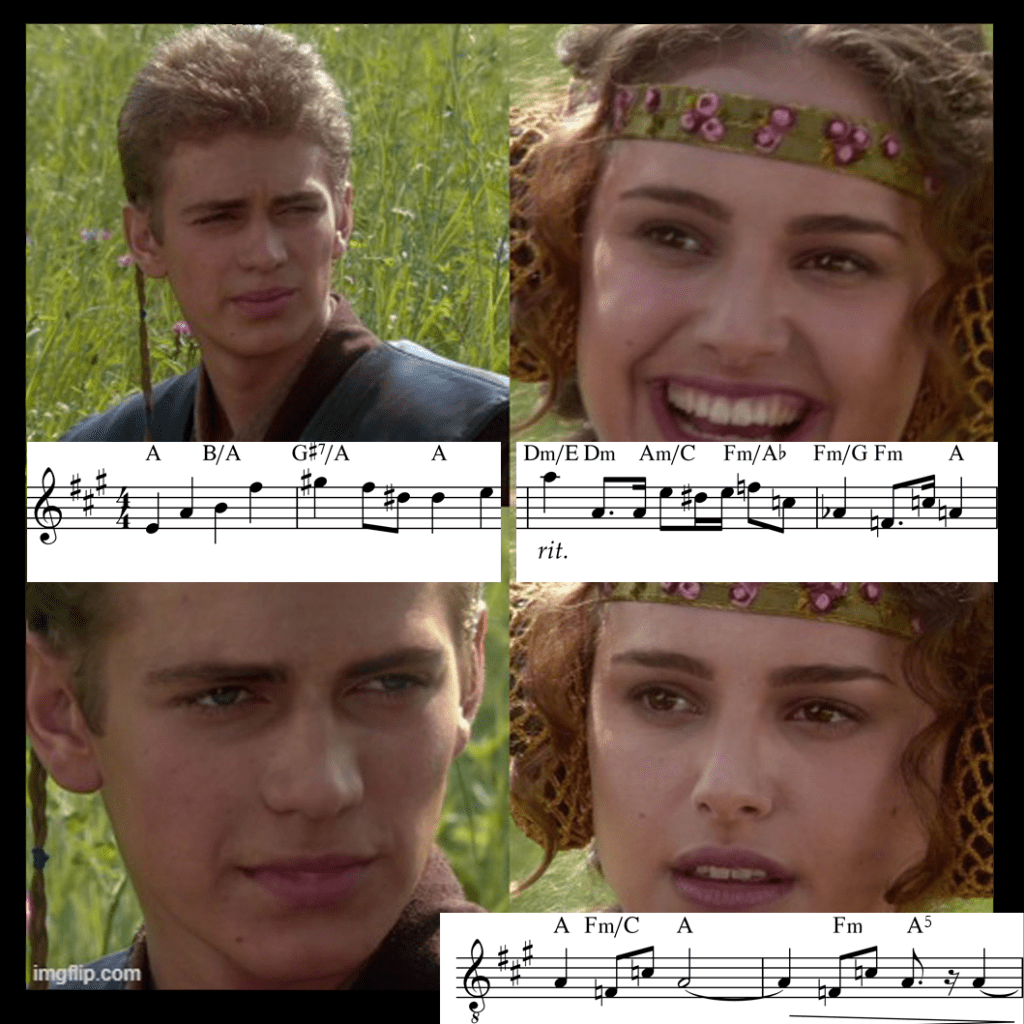

The biggest promissory note was issued for the music of a certain helmeted archvillain. Among the dozen new melodic identifications devised for The Phantom Menace is a melody Williams wrote for the 9-year-old Sith-to-be, Anakin Skywalker. The statement below, which accompanies a wistful conversation between Anakin and Padmé Amidala, is representative.

While Duel of the Fates proved the score’s most iconic set piece , Anakin’s theme is the score’s emotional heart. A traditional and balanced 8-bar period, the tune is saturated with codes for childlike innocence, optimism, and good-will. But Williams also sneaks in some structural twists: dissonant leaps, bristly appoggiatura chords, and rather more chromaticism than one would expect for a melody intended for a guileless youth. Many of these melodic personality quirks (or, better, red flags) are attributable to the figure lurking in the background: Darth Vader’s theme, aka “The Imperial March.”

Anakin’s leitmotif is not exactly a deconstruction of that villain theme to end all villain themes; such would imply something more systematic, more abstract than Williams gives us. Rather, he picks out a few of Vader’s more malign elements and allows them at times to peak through. Those elements are chiefly intervallic, though in elaborated instances, rhythmic and harmonic signatures from Vader are also faintly detectable. In general, the leitmotif retains plausible deniability. “It sounds familiar, very sweet,” Williams noted in an interview with Bob Thomas in 1999. “But if you listen to it carefully, there’s a hint (of evil).”

[For a more sustained and technical analysis of Anakin’s Theme, Dominic Sewell and Melinda Eschenfelder provide detailed accounts of these two leitmotifs in relation to one another.]

Hints of evil can be found everywhere in Episode I’s soundtrack, if you know where to listen. A sense of foreboding hangs over the score, thanks in no small part to the germs of Vader’s theme that Williams seeds throughout. Many of these prefigurations, like the nimble motif that zips through “The Droid Battle,” are not immediately linked to the fate of the Dark Lord at all—a decoupling of signifier and signified that if anything augments the score’s mythic potency. Only once does the Imperial March rear its literal head, when Yoda senses “grave danger” in the prospect of training young Skywalker. Tellingly, that moment does not bear the sound or structure of Anakin’s leitmotif. (An additional instance of Vader’s theme—remarkably, the series’ sole major mode variant—can be heard in an unused alternate for the aftermath of the Battle of Naboo.)

Against this backdrop of constant portent, Anakin’s theme proper is given quite a workout: 20 iterations, more than any other leitmotif in the film. Most renditions stress the “boyish sweetness” aspect over the latent “evil incarnate” one. Nevertheless, it seemed clear at the time of the movie’s release that Williams’s plan was to somehow transform Anakin’s melodic identification back into Vader’s march. Many comments made by the composer, including the one quoted at the beginning of this essay, indicated a real excitement about such future thematic work. Listeners were thus primed to follow Young Skywalker’s leitmotivic career with great interest. (I myself certainly did, going so far as to mock up a MIDI file of the theme back in 97, by ear, rather imperfectly…)

Alas, it was a musical prophecy that misread, could have been.

***

It would be one thing if Williams had simply forgotten the leitmotif after The Phantom Menace. There are, after all, precedents of Vader’s thematic material being treated inconsistently. The original, rather runty Imperial Motif from A New Hope would never be heard again once the infinitely more memorable Vader theme commandeers the score in Empire. But Anakin’s leitmotif does reappear after Episode I. Only, it does so with puzzling infrequence, receiving just one in-narrative iteration in Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith each.

The Episode II statement accompanies the reunion of Anakin Skywalker and Padmé Amidala, underscoring the first snatches of what would become the film’s unrelievedly cringy romantic dialogue. In this scene, the leitmotif serves as a closing bookend for 1m4 “The Meeting of Anakin and Padmé,” a cue also notable for being the first to adumbrate their love theme, “Across the Stars.” (1m4 also pointedly neglects to recall Jar Jar’s motif from Episode I—a more merciful occasion for leitmotivic amnesia.)

The isolation of Anakin’s theme here, and the fact that it is motivated by Padmé’s recollection of little orphan Ani, makes it more an instance of motivic mention than use. What was a dynamic and evolutionary leitmotif in Phantom Menace now reverts to a static reminiscence motif (Erinnerungsmotiv). Still, the citation is not without poignancy. The melody begins in a straightforwardly benign way, but its penultimate chord is shaded ever so slightly darker than it had been in Phantom Menace. This microexpressive shift is communicated not just through harmony, but the way Williams misaligns the tune’s melodic and tonal resolution by two beats—the slightest tear in Anakin’s musical facade.

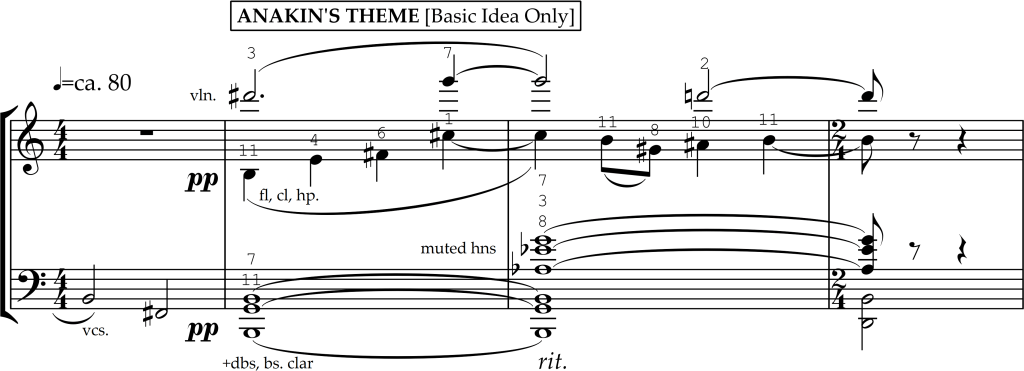

Something much more troubling has impacted the theme upon its recall in Revenge of the Sith, midway through 2m6 (“Scenes and Dreams”). As a tormented Anakin stares off into the night, Williams allows two bars of the score’s solitary instance of his boyhood theme, quietly muttered by flutes and clarinets.

The once cheery tune is here so dissonantly harmonized as to be genuinely bereft of a pitch center. Complex chromatic transformations of originally stable themes are, of course, commonplace in Star Wars, but this moment represents one of the few that approaches true atonality. Richard Dyer, in his 1999 account of the scoring of Episode I, mischaracterized Ani’s leitmotif as being “built on a chromatically unstable 12-tone row,” a that which cursory analysis disproves. (I myself was also under this misconception at the time, and perpetuated it online; in fairness, I was in 9th grade.)

Dodecaphonic or not, if ever there were a moment where Anakin’s melody suggested the chromatic aggregate, this lost little fragment in Revenge of the Sith is it:

Anakin’s melody, so full of promise in Episode I, thus quietly withers away, unloved and unactualized. We cannot know the exact reason why Williams chose to neglect this theme. Perhaps he felt the tune was apt only for Jake Lloyd’s version of the character, and Hayden Christensen’s adolescent Anakin demanded a different melodic identification. But while any critical evaluation of the Prequels as a whole must contend with this lack of leitmotivic follow-through, the music Williams actually wrote for Anakin’s tragic arc is superb. Indeed, some of the most psychologically probing and properly operatic scoring in the whole saga is devoted to Skywalker’s fall.

For example: is there a finer musical depiction of grief turning to rage than this, the transition from Episode II’s 4m6 (“Rescuing Mother”) into 4m7 (“Exacting Revenge”)?

Episode III, with its spasmodic pacing and strange characterizations, can attribute 95% of its pathos to Williams’s sweeping music. The power of cues like “It Can’t Be” and “Padmé’s Visit” seems inversely proportional to the convincingness of writing and performance they accompany. In such scenes Williams does not just compensate, he elevates. And these sequences do not suffer for being predominantly non-leitmotivic; their strength as set pieces stems from being self-contained. It is impossible to listen to the volcanic conclusion to “It Can’t Be” and seriously wish Williams had written anything else.

* * *

All this music charting Anakin’s descent is traditional dramatic underscore. But there is another layer of musical storytelling that happens across the Skywalker Saga, a layer that can be as or even more important than the main non-diegetic soundtrack. Since Star Wars 1977, Williams has produced numerous paratexts: pieces that frame or supplement the score proper. These range from in-film (main titles, end credits) to just outside the film (live-to-picture montages, and, in the case of Episode VII, trailers) to quite separate from it (theme park music, concert arrangements). Of the three dozen or so concert arrangements, some are dispensable, but others are quite essential, developing and nuancing material in a way impossible in the main score, and sometimes playing out mythos-defining character arcs that don’t happen elsewhere! The paratexts also provide a chance for Williams—an inveterate tinkerer—to revisit themes, both as pure musical arguments and vessels for an extramusical program. To really follow the story of Anakin’s leitmotif, you need to consider its treatment within and across these not-so-auxiliary pieces.

The original 1999 concert arrangement, “Anakin’s Theme,” plays with the audience’s foreknowledge that this is a predecessor to Vader’s calling card, with passages that range from subtle to near-explicit invocations of the Imperial March. The central climax (1:46-2:14) involves a melodic line never really heard in The Phantom Menace proper. But listeners who stick around for the credits, which close with this arrangement, will hear an invocation of the 4th through 9th notes of the Imperial March, complete with Vader’s signature flattened minor submediant: here an uncanny F-minor in the key of A.

The topic of Skywalker’s musical fate thus broached, the arrangement’s short codetta presents shards of Vader’s leitmotif more explicitly, and even begins to cloud the lydian glow of the rest of the piece. Williams ends on an A open-fifth chord—neither major nor minor, modally noncommittal but hardly auspicious.

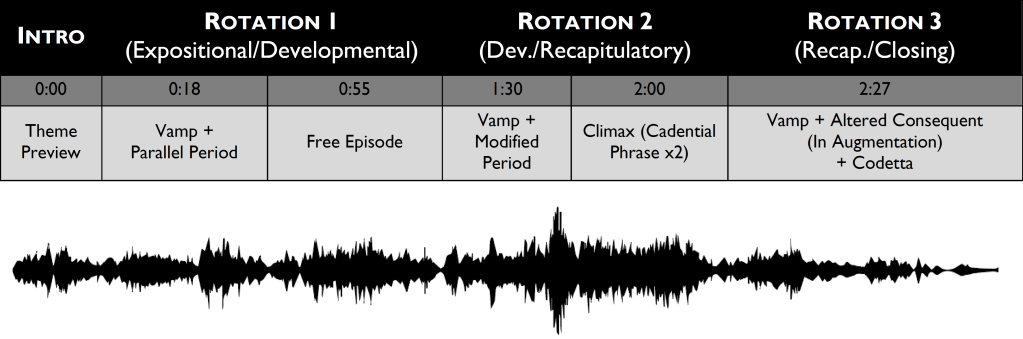

“Anakin’s Theme” in this guise is a great example of through-composition. After the initial statement of the main period, the piece spins out as if one uninterrupted musical thought. Labeled as a “Developmental Core” in the below formal diagram, the piece’s central paragraph blends elements of motivic working-out, recapitulation, climax-building, and (particularly at the end) Imperial-allusion. And while those 23 central measures can be subdivided in a variety of ways, the overall impression is of an unbroken arc of rising and subsiding intensity. Indeed, once it gets going, “Anakin’s Theme” 1999 is the least episodic, most Wagnerian in its approximation of endless melody, of all the Star Wars concert arrangements.

For twenty years, this piece existed in a single version: the one that is heard (twice) on the OST and officially enshrined in The Phantom Menace’s Hal Leonard Signature Edition. Given the way the theme’s development basically terminated after Episode I, the arrangement would stand for two decades as the theme’s most definitive and sustained exploration, a de facto final word for young Anakin Skywalker’s music, albeit one whose ominous final bars signaled a decided lack of finality, a set of tragic story beats yet to be told.

But last year, Anakin joined “Across the Stars” and “Han Solo and the Princess” to become another Star Wars theme that Williams reworked in a profound way. Though not as radically altered in large-scale structure as “Across the Stars” (rev. 2019/21), nor as thoroughly transformed in mood and melodic structure as “Han Solo and the Princess” (rev. 2018/19/21), the changes to “Anakin’s Theme” are not without important formal—and, consequently, narrative—ramifications.

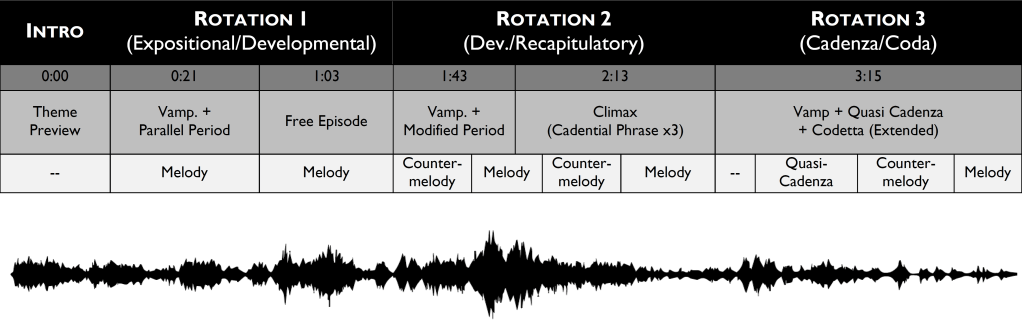

Admittedly, only the most perceptive listeners would have consciously noticed anything different in the first revision, unveiled at Film Night at Tanglewood on August 5th, 2023. The first structurally significant change is an insertion. In the original arrangement, there is a two-measure lydian vamp that prepares the theme’s first and final statements. In the revision, that vamp is heard a third time, slightly modified, at the arrangement’s midpoint (1:30).

Slight though the interpolation may be, this vamp effects a rebalancing of the piece’s overall form. “Anakin’s Theme” now takes on a more traditionally sectionalized aspect, seeming to restart itself several times, in a way characteristic of a large-scale ternary form. In some ways, this midstream recollection of framing material is to the arrangement’s benefit: the piece sounds a little more internally corroborated, more cumulative, more substantial. With the three equally spaced iterations of that thematic introduction, the arrangement takes on a rotational quality, a series of passes through the same thematic materials in the same order. Speaking more metaphorically, it is as though Anakin’s melody is going through three trials. It is left to the listener to judge if he passes those trials.

The clarification of formal structure lent by this extra vamp comes at a cost. The added bars create a hypermetrical hiccup with respect to the mostly quadratic phrase structure of the piece, a discrepancy that can be massaged with a smooth performance. More significantly, the 2023 revision sacrifices the sense of fluidity of the original. In the 1999 version, the internally modulating restatement of the theme at 1:25 feels like a consequence of the more freely developing material that precedes it. Now, in this less through-composed form, it just sounds as if we’re restarting our engines.

The other difference in Williams’s first 2023 revision is an extension. The affected passage is the closing restatement of Anakin’s motif at 2:27. The melodic line is essentially unchanged, save for one substitution of G#4 for A4 at 2:45—a tiny masking of the octave descending figure’s otherwise manifest origin in the Imperial March’s fifth measure. Williams slightly elaborates the bass line, extending the chromatic descent in its final idea and creating some new pricks of dissonance in the process. But the main change is one of rhythm: the melody is expanded in duration, turning a thought that initially took 14 beats to complete itself into one that now lingers for 25. The effect is not so much one of a written-out diminuendo as a collapse of the sturdy metrical edifice that had been supporting the theme thus far. Again, there is a rebalancing that results, not of formal divisions but emotional emphasis. The end of “Anakin’s Theme” in 1999 was already foreboding, but efficiently so, a whisper of warning that was over before one could really sonically resolve it. However, with these four measures in the 2023 version stretched out like taffy, the listener is forced to dwell on what will become of that once innocent, now estranged melody.

Both the 1999 and first 2023 versions of this concert arrangement become less about Anakin’s merry tune than Vader’s wicked anthem as they progress. This trajectory mirrors both the character’s and leitmotif’s fate. The Phantom Menace score is all about Anakin’s shiny new leitmotif, with the Imperial March being but a vague potential. In Clones and especially Revenge, the scores are more concerned with the mature Dark Lord’s motif. With each new cue, Williams conceals it less and less, until the anthem is fully, unapologetically brandished at the end of Episode II in association with the rise of the Imperial war machine, and again at the midpoint of III for the official dubbing of “Darth.”

The shifting of focus from Anakin to Vader is underlined heavily in the third and final take on the concert arrangement: Williams’s setting for violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, which premiered in Pittsburg on December 12, 2024.

This was to be the seventh (!) Star Wars theme to be thus Mutterized. “Anakin 3.0” as heard in Pittsburgh occupies a different expressive universe than the purely orchestral arrangements, even though its basic form is mostly the same as versions 1 and 2. The presence of a soloist necessarily makes a piece less universal, more about an individual protagonist’s unique timbral voice—even if that voice was nowhere associated with the leitmotivic target in the originating score. (In fact, there is but one instance of solo string scoring in the Skywalker Saga: a ten note cantilena for cello in its expressive 3rd octave, providing a preface to “Across the Stars” in Revenge of the Sith’s 2m6 “Scenes and Dreams”.)

The Mutter arrangements were always foremost about showcasing that virtuosic voice, rather than articulating or reinforcing a narrative. But Anakin’s Theme in the hands of Anne-Sophie accomplishes this narrative enrichment nonetheless.

The alterations that most stand out in this third go at the theme are, of course, the solo passages. For the first third of the piece, Mutter simply covers the main melodic line, though starting in the second rotation (1:30), her part alternates between Hauptstimme and counter-melodic embellishment. The climactic passage is enlarged with an extra third pass through the theme’s Vader-esque cadential phrase (2:48), this time more delicately scored, with the orchestra’s bass entirely dropping out. Anakin’s Theme sounds positively angelic here. Angelic, until the low strings return, that is, and with them those baleful F-minor chords that, harmonically speaking, are the root of the theme’s eventual turn to the dark side.

The final minute and twenty seconds are where the most profound formal and affective transformations take place. After yet another slight alteration to the lydian vamp, the whole conclusion settles on a low A pedal. Above this immovable tonal object, Mutter unfurls a quasi-cadenza, florid but somehow also low-energy, based on the same phrase that was rhythmically augmented in Version Two, its F-minor taint now spread to maximally concerning levels. The cadenza/coda section makes text what in prior versions was subtext: this is fully Vader’s theme now.

The final two phrases, for solo harp and violin respectively, are particularly overt. The choice of harp is telling: this was, of course, the instrument that provided the final word for Vader’s theme in Return of the Jedi upon his death. (A cue reused, or better recompiled, to interesting effect in The Rise of Skywalker.) Williams’s arrangement for Mutter fades off into infinity, in the manner that many of Williams’s more contemplative concerti do. While a drawn-out morendo like this is unlikely to bring the concert house down for its virtuosity, it is a brilliant ending, and a chillingly effective way to lay Anakin to rest (again).

***

Anakin’s Theme appears in one other context, and it is arguably the most essential to its thematic arc. The End Credits for Attack of the Clones conclude with a thematic succession that encapsulates the journey from slave boy to love-sick teen to Sith Lord. The suite is mostly based on the love theme for Anakain and Padmé, a.k.a. “Across the Stars.” This is a theme every bit as remarkable as “Anakin’s,” and maybe prefigured—just barely—by a triplet figure in the latter’s middle section. But Williams initiates the coda section with an explicit recollection of Anakin’s tune, now carried by forlorn horn:

Only the antecedent phrase is completed, with the music immediately turning to the tragic love theme. That too is unsettled, its bass slouching toward the Imperial March. A micro-cadenza for flute follows, it too is based on the contours of “Across the Stars” but now undergirded by Vader’s theme in double basses. And then the music stops, not in some ambivalent half-major, half-minor realm, but the pure blackness of E-minor.

Incredibly, this coda—the only place where all three stages of Anakin’s fall from grace converge—was cut from the film, in favor of a straight repetition of the “Across the Stars” concert arrangement, which does not end this way. Only those who heard the soundtrack album will ever have accessed this essential part of the telling of Star Wars’ musical myth.

***

The Skywalker Saga is a big, complicated, messy thing, and coming to terms with all its texts and paratexts can be a bewildering experience. Thematic arcs can be promised and then dropped. Seemingly crucial cues may be cut from film, album, or both. And the same story can be told musically multiple times and in multiple ways. This textual complexity was present even in A New Hope, but was supercharged in Phantom Menace, with the treatment of Anakin’s Theme being just one example of the increased knottiness of Williams’s contributions. But Episode I remains an exquisite score, a qualified masterpiece retroactively made even better by its paratexts. For those open to complexity and some frustration, to symphonic mythmaking that does not always go the way initially promised, The Phantom Menace, along with the whole of the Prequel Trilogy, is truly, deeply, great film music.

Frank Lehman is an Associate Professor of Music at Tufts University. He is the author of Hollywood Harmony: Musical Wonder and the Sound of Cinema, editor of Film Music Analysis: Studying the Score, and has published articles in academic and public venues on film music and John Williams. This essay is adapted from the eighth chapter of his forthcoming book, The Skywalker Symphonies: Musical Storytelling in Star Wars, under contract with Oxford University Press.