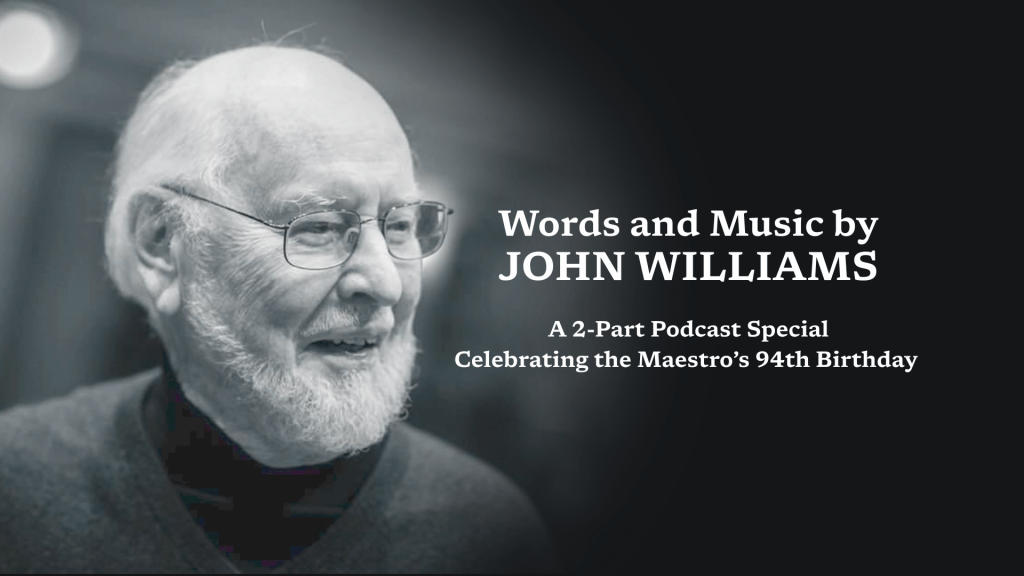

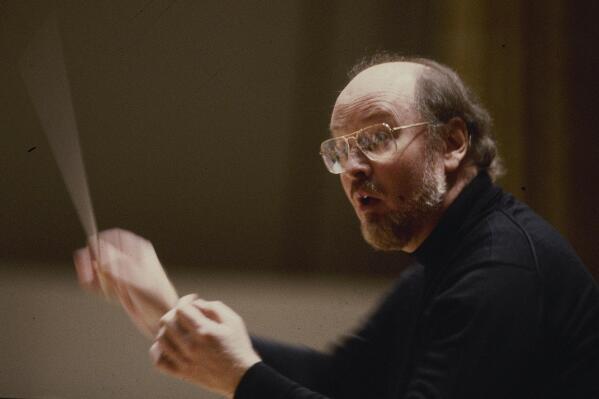

By 1984, John Williams was coming to the close of a decade that saw him rising from sheer obscurity to the world’s best-known composer. Starting in 1975, his music to Jaws helped define the concept of the summer blockbuster. The decade not only saw the formation of the relationship between the composer and his director Steven Spielberg with a quick succession of hits (and one flop), but saw another important collaboration being forged with Star Wars creator George Lucas. Throughout the decade, Williams scored one of the top-grossing films of each year (with the exception of 1979), closing in 1984 with the second Indiana Jones adventure. While recording Star Wars, another important partnership came to life: After working with the prestigious London Symphony Orchestra, the success of George Lucas’ space opera made the John Williams/LSO package desirable for any big adventure/fantasy Hollywood production. (In turn, this also benefited the orchestra enormously, as requests for many Hollywood high-profile productions kept pouring in, even without Williams). The success of all those big, muscular, symphonic film scores helped to propel Williams’ own career as a public conductor. Having been a working conductor at the studios for most of his career, he had never invested much time or energy in his public conducting engagements. After Star Wars, all of that started to change and soon enough he was conducting his own music around the United States and Great Britain and even replaced an ailing Arthur Fiedler for a concert at the Hollywood Bowl[1]. That in turn took him to Boston, as in December 1979 he was announced conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra as the successor of Fiedler (who had passed away the previous summer). Boston offered John Williams a stepping stone the likes of which no other composer in Hollywood history had ever had. He was able to perform his music and that of his peers on popular stages with one of the finest orchestras in the United States, allowing it an exposure that, at the time, still was not really accepted by the elite-oriented classical establishment.

Leading the orchestra in Boston also allowed him to find new ways to express himself musically. Until then, Williams had already created a decent catalogue of concert works, but all of them were more serious exercises of classical forms[2]. None of those were short works, and some of them were rather serious in tone and sometimes quite demanding for the listener (and far removed from the otherwise accessible idioms of his film scores). As soon as he started his tenure with the Boston Pops Orchestra, not only did he prepare for concert performances some of his film music, but he also started creating a new body of work, comprised of shorter, festive pieces to be performed at special events. During his first four years in Boston, he composed quite a number of these festive pieces, all of them related to Bostonian events or the orchestra itself. These pieces quickly become hits with the audience, not only in Boston but across the country thanks to the popular “Evening at Pops” series on television.

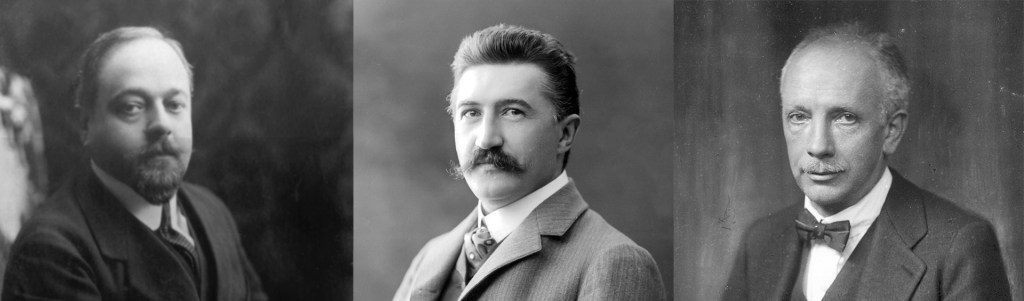

The Olympic Games and music have always gone together. Right from the start, music was an integral part of all major ceremonies and established with medals offered to the most important musical contributions. Starting with the first games of the modern era in 1896, an official theme was composed, The Olympic Hymn by Greek composer Spiro Samaras. This has remained a recurring custom throughout the now century-long tradition of the games, and quite regularly new music was commissioned to give each Olympiad its own character. For the III Olympiad of the Modern Era, the first set in the United States, music was either drawn from pre-existing pieces that somewhat conveyed the spirit of the games (a practice that remains to this day) or was commissioned for the St. Louis World Fair (the games were originally to have been set in Chicago but the International Olympic Committee ended up going for the city hosting the World Fair). When the games returned to US soil for the X Olympiad in 1932, a contest for a new Olympic Hymn was launched and a first prize was handed to American pianist Walter Bradley Keeler. While his piece was to be used as the games official anthem, it was instead Josef Suk’s Toward a New Life that become largely associated with the 1932 games. A former pupil of Antonin Dvorak, who married his teacher’s daughter, Suk’s piece was so well-received it even won a Silver Medal. Keeler’s music, which was originally expected to replace Samara’s Hymn that had almost been forgotten during those years[3], faced harsh scrutiny due to its lyrics. They weren’t approved by the German Nazi Regime hosting the following games of 1938, and eventually Keeler’s Hymn fell into oblivion (for the Berlin games, Richard Strauss provided a new Olympic Hymn). Prior to the 1984 games, the Olympics would return to the United States two more times, both for the Winter Games in 1960 (Squaw Valley) and in 1980 (Lake Placid). On both occasions, no major American composer was offered a commission. Composer/Pianist Lukas Foss (a close friend of Leonard Bernstein’s) came close in 1980 with his piece Round a Common Corner for chamber ensemble and narrator, but it wasn’t composed for an actual Olympic event and rather for a documentary shown during the games. In 1981, Leonard Bernstein himself contributed a new Olympic Hymn, namely for an International Olympic Congress in Baden-Baden, but the music, based on an excerpt from the flop musical 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue (later reworked into A White House Cantata), was eventually forgotten. No other than John Williams himself resurrected the hymn and conducted the premiere recording for the 1996 official Olympic centennial album.

So by 1984, no American composer had effectively contributed to the library of Olympic ceremony music during the 88 years of the modern era games. The Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee clearly had that in mind as several American composers were commissioned to write music for the main ceremonies, ranging from jazz giant Herbie Hancock and minimalist superstar composer Philip Glass to, of course, John Williams. Other composers included Quincy Jones, Bob James, Bill Conti and Marvin Hamlisch. Fresh from his aforementioned string of success, Williams was just one step away from becoming America’s favourite composer. He landed the commission for the actual musical signature for the Los Angeles games, coming up with a heraldic fanfare (made up of two contrasting and distinct phrases) that leads to a theme that embodies the sense of honour, pride and glory associated with the Olympic gold. The opening fanfare is far from simple, even though the range of notes that the composer could use was limited by the valveless herald trumpets that were used during the opening and medal ceremonies. The second phrase of the fanfare returns cyclically during the Olympic theme portion, closing the piece in thunderous blasts of joyful glory.

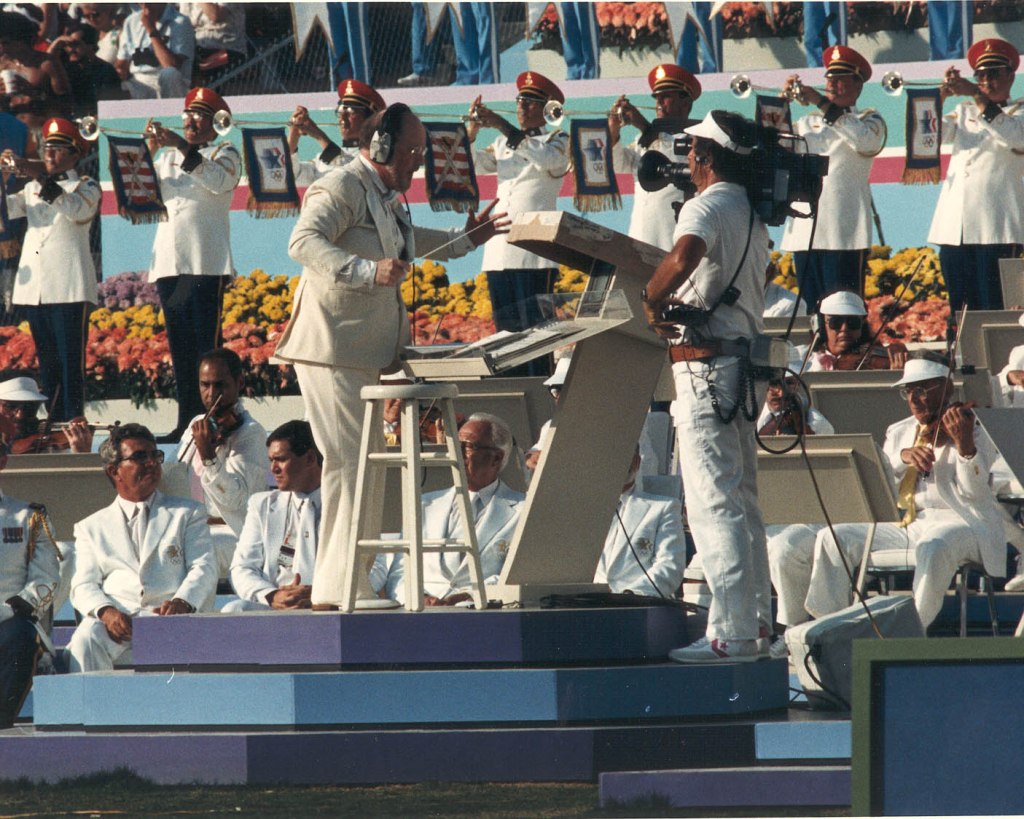

For the Opening Ceremony, Williams conducted the New American Orchestra along with an extra ensemble of herald trumpets[4] at the Los Angeles Coliseum on July 28, 1984. Nevertheless, this wasn’t the actual premiere of the Olympic Fanfare and Theme. Williams conducted its first performance at Boston’s Symphony Hall with the Boston Pops at the annual ‘President at Pops Night’ concert on June 12. The piece was performed a few more times in Boston and received its west-coast premiere just the day before the opening ceremonies with Michael Tilson Thomas conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl in a concert aptly titled ‘Prelude to the Olympic Games’. Looking from our vantage point 40 years later, it’s obvious that the contribution offered by Williams made a large impact on the musical literature for the games and in the process became a sort of musical signature for all things Olympic. Within the composer’s own body of work, it clearly marked the importance of John Williams as the preeminent composer for big nationwide and international events. Shortly after the Olympics in Los Angeles, Williams contributed his composition Liberty Fanfare to the rededication of the Statue of Liberty in 1986. Throughout the years he added many of these ‘little’ pieces for all kind of events, including the subdued chamber piece Air and Simple Gifts (2008) for Barack Obama’s first inauguration. Many of those compositions had their roots in the composer’s relationship with the Boston Symphony family but often went beyond the city walls to reach a much wider audience (as exemplified by Aloft … To the Royal Masthead in 1992 for the visit of Prince Philip to Boston, Sound the Bells in 1993, Happy Birthday Variations in 1995 and Song for World Peace in 1996). The most recent of those pieces, the Fanfare for the Vienna Philharmonic Ball (2023), resulted from a commission by the Vienna Philharmonic and was first performed alongside the famous fanfare by Richard Strauss which has been used for the debutante procession since the inception of the ball in 1924.

The Olympic Fanfare and Theme also marked the start of two longstanding collaborations and a trend for Williams’ future projects. Since 1984, Williams has written three more pieces for Olympic events plus one for the special Olympics, building a relationship with the Olympic Committee and eventually becoming the composer who wrote for more Olympic occasions than any other. For the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, Korea, Williams was commissioned by NBC to write Olympic Spirit to be used during the broadcasts in the United States, but eventually was sanctioned by the International Olympic Committee and was also used during the opening ceremony. In 1995, Williams was commissioned by the IOC to write the Centennial signature theme for the Summer Games of the following year that took place in Atlanta. The full version of the six-minute Summon the Heroes features antiphonal brass and an extended and demanding solo trumpet section (worthy in itself of Olympic gold) in a piece that completely encompasses Baron de Coubertin’s Olympic ideals. At the opening ceremony, Williams conducted the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra with a supplement of herald trumpets placed all across the stadium in an abridged 3-minute-long version of the piece. Both versions are featured on the official album of the Centennial of the Modern Olympics, which also included Williams’ previous Olympic compositions as well as that of other composers from past games and even Michael Torke’s Javelin, another piece written for the Atlanta Games. Finally, for the 2002 Winter Games in Salt Lake City, Williams wrote Call of the Champions for chorus and orchestra, employing the 360 voices of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Williams made use of the Olympic motto ‘Faster, Higher, Stronger’, sung in Latin throughout the piece. For the final statement, the composer added ‘Clarius’, a word that can be translated (within the context) as clarity of mind. Williams would eventually address the use of choir as both an opportunity to use the famous Utah-based choir and to reflect on recent tragedies through the use of the human voice.

Fifteen years earlier, in 1987, Williams penned We’re Lookin’ Good for the U.S. Special Olympics (an upbeat march reminiscent in parts of the march for 1941) with lyrics by the composer’s regular collaborators Alan and Marilyn Bergman and sung during the ceremonies by the athletes. Not only did Williams become the composer to have been commissioned for more Olympic events than any other, he was also awarded the Olympic Order in 2003, recognizing ‘his significant contributions to the Olympic movement through his iconic compositions’.

Williams’ frequent association with the Olympics led to another collaboration, this time with broadcaster NBC. In 1985, he wrote a set of four themes for NBC News, and just a few years later he returned to NBC’s sports branch to write music for the U.S. broadcast of the Olympic Games. NBC Sports had just closed a deal to broadcast the 1988 Olympics and upcoming games but were unable to use a short brassy fanfare by French composer Leo Arnaud, Bugler’s Dream, due to copyright licencing issues. This fanfare was strongly associated with the games in the United States due to previous broadcasts on ABC. As mentioned before, Williams provided The Olympic Spirit, a piece eventually approved by the IOC. From then on, Williams kept returning to NBC to deliver updates on his previous themes and compose new material, be it for NBC News, NBC Olympic broadcasts[5] or NBC Sports, most notably their 2005 commission for the company’s Sunday Night Football[6] broadcasts.

And that is another trend that started in the 80’s with The Olympic Fanfare and Theme: Williams became fashionable to contribute music to sport events of many different kinds. In 1989, he wrote the Winter Games Fanfare for the Alpine Ski Championship in Denver, two special arrangements of The Star-Spangled Banner (for band in 2004 and for brass in 2007) which preceded season-opening baseball games, Fanfare for Fenway in 2012 and last year’s Of Grit and Glory for the ESPN College Football Championship.

The impact of Williams’ particular 1984 piece on his career is obvious. Even more striking is how it shaped the perception of the audience when it comes to the sound of the Olympics and of other special events. As Williams recalls, in this sort of events ‘the orchestra role is mostly… a lot of brass and cymbals and drums. I guess, for the obvious reasons, we think of these openings as being something that’s done with great pageantry, and flags, and colour, and lights, and parades… and great crowds. And the music is loud!’[7] Forty years on, various composers try to capture the glory that comes with the Olympic gold with large orchestral pyrotechnics, in some way trying to emulate the sound that John Williams helped to create. His music is synonymous with bigger-than-life efforts (so well represented by the Olympics) and more than anyone else, John Williams is the Olympic composer. Not only because he has written more music for Olympic ceremonies or broadcasts than anyone else but because he is the embodiment of the struggle to run the extra mile, to be faster, higher and stronger. And even when the aim is the highest glory, he always fought ‘as a friend, not as a foe…’[8]

In the end, the words of the composer himself say it best. While addressing the inspiration for his Olympic Fanfare and Theme, he described its legacy and impact on all of us: “[It] continues to fascinate and inspire each one of us (…). The human spirit soars and strives for the best within us.”[9] Such is the power of Williams’ music.

An overview of the Olympic Fanfare and Theme discography

The following is a personal list. It’s a list of a few of the many commercial recordings of Olympic Fanfare and Theme released over the last 40 years that I personally feel every committed fan should at least listen to once. This isn’t a ‘best recording’ listing in any sense and shouldn’t be taken as such. Some of these recordings are historically relevant, others might be interesting for some curiosity, but all of them are special to me for one reason or another. In the end, if pressed, I would pick the last one as my favourite.

1984, Studio Orchestra/John Williams

from “The Official Music Of The XXIIIrd Olympiad Los Angeles 1984”

CBS/SONY 35DP 200

This has the distinction of being the first recording of the Olympic Fanfare and Theme. It was recorded in Los Angeles with a studio orchestra, and while it is a fine performance, it lacks the opulence and exhilaration of some later readings of the piece. For collectors it might be of additional interest due to the rarity of the CD release. The vinyl, in its several incarnations, can still be found in good condition at an affordable price but the limited CD pressing from Japan is very rare and is always going for rather high prices.

1987, Boston Pops Orchestra/John Williams

from “By Request… The Best Of John Williams And The Boston Pops Orchestra”

Philips Classics 420 178-2

A more interesting performance, doomed by a terribly done edit on the opening fanfare. If you can get past the obtrusive edit, this recording offers all the lushness of the Boston Pops and its Symphony Hall in Boston. As a kid, the Olympic Fanfare and Theme defined the Olympics for me, and this ended up being the first recording I had, understandably holding a special place on my list. Again, if you can live with the dreaded edit, this is a nice recording. Originally released on Philips Classics, I believe it can be easily tracked down on Decca Records or on any of the many compilations of Williams recordings by Philips. The original album might look like a compilation of Williams’ evergreens as it gave a wonderful overview of his career until that point, featuring material from previous Boston Pops recordings and a few newly recorded ones, including the Olympic Fanfare and Theme.

1987, Cincinnati Pops Orchestra/Erich Kunzel

from “Pomp and Pizazz”

TELARC CD-80122

The year 1987 brought us, next to “By Request…”, what I consider the best recorded performance of the original version of the Olympic Fanfare and Theme. Anything under the baton of the other “Pops” conductor Erich Kunzel was a sure bet in the 80’s and early 90’s. Back in 1979, Kunzel had been a contender for the Boston Pops conducting post that eventually went to Williams. He was a friend and champion of Williams’ work, having recorded a wealth of music some of which wasn’t easily available on CD back then (SpaceCamp being a prime example) and was close enough to Williams to ask him for the original scores. Many of Kunzel recordings during this period made for the audiophile label TELARC were very precise and benefited from a well-rehearsed ensemble and a truly great sonic capture by the tech personnel. Even though this particular album only includes one Williams’ piece, fans might like to check out the remaining program because it comes with great music of pomp and circumstance (pun intended, as Elgar’s famous first march is included) and even includes another Olympic piece, Suk’s Toward a New Life, all in marvellous and breathtaking performances.

1996, Boston Pops Orchestra/John Williams

from “Summon the Heroes”

Sony Classical SK62622

Since the 1960’s, Bugler’s Dream by Leo Arnaud had been strongly associated (at least in the United States) with the Olympics as ABC used it during their broadcasts. By 1988, NBC had secured the rights for the broadcast within the US but missed the rights for the Arnaud fanfare. Hence the commission of Olympic Spirit in 1988. For the next Summer Games, held in Barcelona in 1992, Bugler’s Dream was brought back to the broadcast playlist and Williams prepared a revised version of his own 1984 piece that would start off with the Arnaud fanfare. Four years later, when the Summer Olympics returned to the United States for their centennial, Williams did not only compose Summon the Heroes, the official centennial theme, but also recorded the official Olympic album with the Boston Pops Orchestra. For that program he presented Summon the Heroes as well as music from previous Olympic events, including his own. Instead of recording again the original version of the Olympic Fanfare and Theme, he used the arrangement NBC had asked for in 1992, making this a highly relevant recording within the piece discography. Although, on a personal level, I’ve never been much of an admirer of this particular arrangement, the performance is a quite solid one and the whole album is an amazing collection of hundred years of Olympic music.

2019, Los Angeles Philharmonic/Gustavo Dudamel

from “Celebrating John Williams”

Deutsche Grammophon 483 6647

Star conductor Gustavo Dudamel commercially recorded the Olympic Fanfare and Theme twice. The first one, going back to the original version of the piece, comes from a 2014 gala concert at Disney Hall. The Olympic Fanfare and Theme opened the concert with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, accompanied by the U.S. Army Herald Trumpets. In the end, there were just too many trumpets so that their sound at times drowned out the rest of the ensemble. (The Blu-Ray is on C-Major label, but you can check the video here.)

In January 2019, Dudamel conducted the same ensemble for a number of concerts “Celebrating John Williams”, more or less mimicking the program for the cancelled Vienna concerts that would have been Williams’ debut with the Wiener Philharmoniker a few months earlier. Again Dudamel opens the program with the Olympic Fanfare and Theme. The 2-CD set met with mixed reviews but I for one enjoy most of it and the performance of the 1984 Olympic theme is of particular interest for two reasons: It marks the recording debut of a revised version of the Fanfare portion of the piece, being now shorter than the original version (it also drops the Bugler’s Dream intro) and it is also the only recording I know of that used the organ (most notably in the coda) to grand effect. That alone makes it worth checking out. (One should note that on the published score there is no reference to the organ, not even as an option.)

2022, Berliner Philharmoniker/John Williams

from “The Berlin Concert”

Deutsche Grammophon 00289 486 2003

My desert island version. By 2022, Williams had stopped using the 1992 arrangement with the Bugler’s Dream intro and for his Berliner Philharmoniker debut he opened the concert with the final revision of the piece (discussed above). It might have helped to be in the audience of this concert, but honestly: I can’t find a match to the precision and verve of the Berlin musicians. They simply made the piece their own. Enough said. Go listen to it.

and a few of other things…

2018, Miho Hazama’s m_unit

from “Dancer in Nowhere”

Verve Records UCCJ-2162 (Japan)

Williams’ music has often been performed by jazz musicians and the Olympic Fanfare and Theme has also been given the jazz treatment. While one can browse the internet for other takes on it, I’ve been drawn back to this one since I first heard it some years ago. A female New York-based Miho Hazama provides an exciting arrangement for her m_unit band that breaks away from Williams’ music just so much as to remain faithful to it. This rendition might not be everyone’s cup of tea but I do find it quite a marvellous take on Williams’ timeless composition.

2018, arranged for band by Jay Bocook, Dallas Winds/Jerry Junkin

from “John Williams at the Movies”

Reference Recordings RR-142SACD

There are just too many arrangements of the Olympic Fanfare and Theme for band and even more recordings to know them all and make a good choice … so I just went with the arrangement Williams himself picked up when guest-conducting the United States Marine Band in 2003, namely by band composer and arranger Jay Bocook. Bocook’s transcription follows the original 1984 score with the necessary adaptations for a winds band. The Williams’ performance of 2003 was recorded by the Marine Band and released as a promotional 2-CD set, and while that set might be hard to track down, the band was kind enough to make the audio available here.

As for availability: The same arrangement was recorded by another top winds band, the Dallas Winds, under their music director Jerry Junkin, himself a champion of Williams’ music. Always the perfect curtain raiser, the Olympic Fanfare and Theme opens an album of Williams’ music arranged for band with astounding performances throughout. Just as the jazz arrangement, this might not be to everyone’s taste, but the renditions remain faithful to the composer’s intentions and are worth checking out.

A very special thanks to Markus Hable for proofreading the article.

References

Burlingame, Jon: ‘Origins of those Olympics themes’, TV Update, 26 July 1992

https://jonburlingame.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/JWOlympicsTVUpdate7-92.jpg

Cousin, Aja: ‘John Williams composed Olympic gold before 1984 LA Olympics’, 2024

https://eu.usatoday.com/story/graphics/2024/07/19/olympic-fanfare-john-williams-1984-olympics-los-angeles/74282017007/

Eldridge, Jeff: ‘Olympic Fanfare and Theme’

https://johnwilliams.org/compositions/concert/olympic-fanfare-and-theme

Guegold, William K.: ‘100 Years of Olympic Music – Music and Musicians of the Modern Olympic Games 1896-1996’, Golden Clef Publishing-Mantua, Ohio, 1996

Guion, David: ‘Olympic fanfare(s): John Williams and Leo Arnaud’, 2012

https://music.allpurposeguru.com/2012/08/olympic-fanfares-john-williams-and-leo-arnaud/

Klugue, Volker: ‘The Story of the Olympic Hymn: the poet and his composer’, 2015

https://music.allpurposeguru.com/2012/08/olympic-fanfares-john-williams-and-leo-arnaud/

Lauritzen, Brian: ‘In Defense of John Williams’, 2012

https://brianlauritzen.com/2012/07/28/in-defense-of-john-williams/

Rogers, Thomas: ‘Olympic Fanfare’, New York Time, June 13 1984

https://www.nytimes.com/1984/06/13/sports/scouting-olympic-fanfare.html

[1] Be sure to check the excellent article by author and journalist Tim Grieving on Williams appearances at the Hollywood Bowl, that also chronicles his rise as a concert conductor https://thelegacyofjohnwilliams.com/2024/07/10/john-williams-hollywood-bowl-phenomenon/

[2] Williams’ body of concert works by then included Concertos for Flute (1969) and Violin (1974/76), an Essay for Strings (1965), a Symphony (1966) and a Sinfonietta for winds (1968), among a few others. The shortest of the pieces, the jazzy Prelude and Fugue (1965), is almost 10 minutes long, and (while using a more popular idiom) is strongly rooted in classical forms and traditions.

[3] Samara’s Hymn indeed lost some of its importance from the 1930’s throughout the 1950’s. Over this period, it was absent on several musical line-ups of the major ceremonies, but eventually it made a return and became the official Olympic Hymn of the International Committee in 1960.

[4] Those same herald trumpets would play the opening fanfare of the piece at the presentation of the medals during the 16 days the games lasted.

[5] For the Olympic broadcasts Williams provided new material and arranged his previous pieces. The one more often returned to was always the 1984 Olympic Fanfare and Theme, providing both new arrangements and recordings of the full piece. More notable was the revised fanfare section, removing part of it in favour of Williams own arrangement of Arnaud’s Bugler’s Dream. Unfortunately, the new material Williams wrote for NBC’s broadcasts remains unreleased.

[6] Williams’ Sunday Night Football material is made up of three different pieces. The first of the set, Wide Receiver, was prepared by the composer for proper concert presentation in the form of an adrenaline-filled march and has been widely played in concert.

[7] John Williams quoted from the Call of the Champions EPK, Sony Classical, 2022. Retrieved at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BiCGgt4SKb8

[8] From the text by Günter Kunert for Bernstein’s Olympic Hymn (1981).

[9] Quoted from John Williams’ note for the 1984 album release.