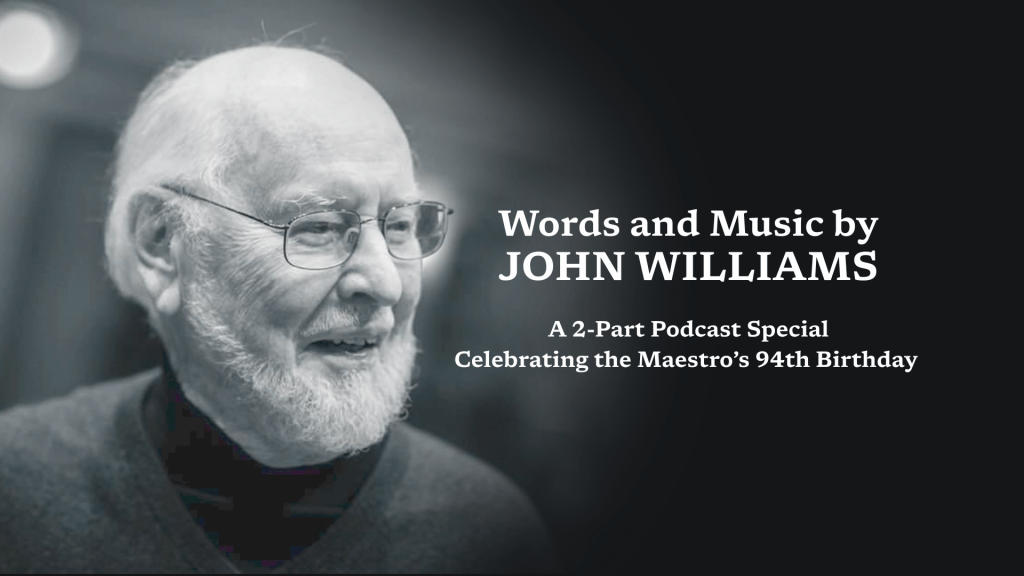

Hosted by Maurizio Caschetto and Tim Burden

Featuring Mike Matessino

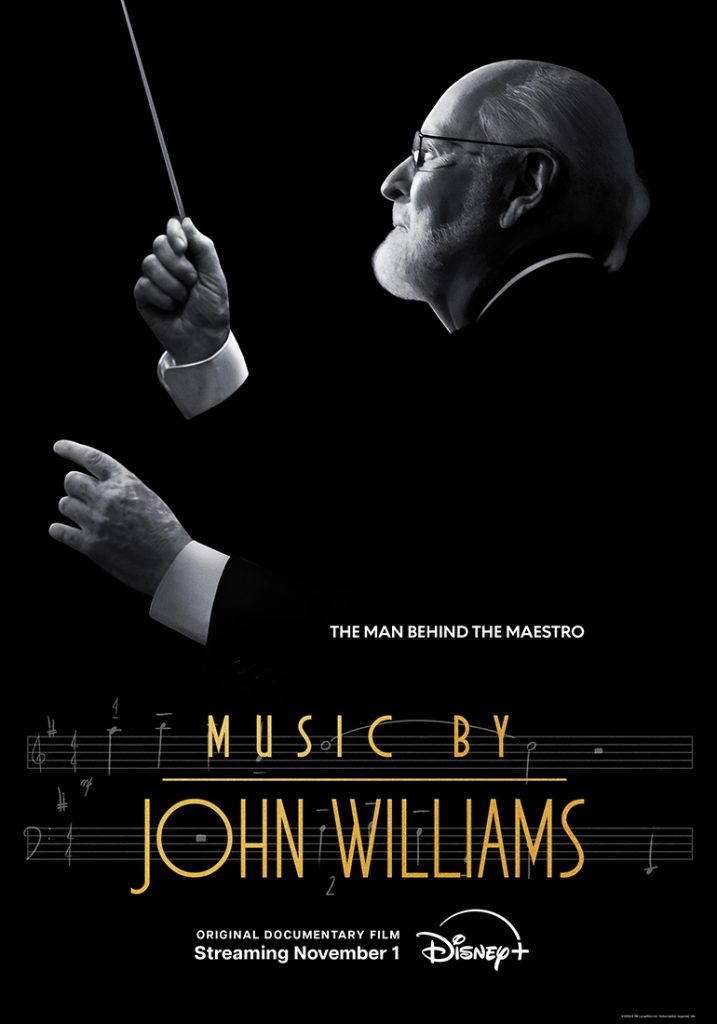

As part of its ongoing podcast series, The Legacy of John Williams presents an exclusive interview with Laurent Bouzereau, the director of Music By John Williams, the documentary film dedicated to the life and career of John Williams, now available for streaming on Disney+. Produced by Steven Spielberg and Ron Howard among others, Music By John Williams presents the life’s story of the legendary composer, who himself sits in front of the camera to recollect and reminisces the numerous highlights of his incredible career, with many of his closest friends and collaborators offering stories and insight about his timeless music.

In this interview, Laurent talks about the honour and the responsibility of creating the first documentary film on John Williams, his lifelong love for the music of the Maestro and why he made the film thinking about future generations. Joining the conversation is archival soundtrack producer Mike Matessino, who also worked as Music Consultant on Music By John Williams.

Special Thanks to Rebecca Bass and Raegan Cutrino at Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures for their kind help and assistance.

For The Love of Music: A Personal Reflection on Music By John Williams

by Maurizio Caschetto, Editor of The Legacy of John Williams

For many years, fans and admirers of John Williams have dreamed of a feature-length documentary film on the life and career of the “Maestro of the Movies,” as he is often called. Given his widely acknowledged position as one of the greatest composers – if not the greatest – working in films, but also as an all-encompassing musical artist of the 20th and 21st century, it seemed not much a question of if this would happen, but only when it would have. Williams has always been notoriously reticent at pointing the spotlight on himself—despite being a very public figure, the composer has showed no tendency to put himself on the center stage. His humble demeanor and no-nonsense attitude are trademarks of his character and certainly among the reasons why he is so beloved and respected by his peers and colleagues. So it doesn’t come as a surprise that over the years Williams always declined requests to participate in such projects as an authored biography, either written or filmed. “My life is not interesting enough,” used to say the composer to many historians and documentarians who approached him over the years. The same words were initially spoken to his longest-running collaborator and personal friend Steven Spielberg, who knocked at Williams’s office door a couple of years ago to pitch him the idea of making a documentary about himself, strongly convinced that his beloved composer friend had a life story worth being told to the world. Finally, Williams mellowed and acquiesced to the project, reassured by the fact it was spearheaded by Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment, in collaboration with Imagine Documentaries and Lucasfilm. The involvement of people and production companies close to the composer felt like a family gathering of sorts, aptly orchestrated by the person in charge of directing the film (and who first pitched the idea to Spielberg): the award-winning filmmaker and documentarian Laurent Bouzereau. He was the one anointed with the privilege and the responsibility of putting together the first authored documentary film on the life and career of Maestro John Williams. Like everything associated with this composer, it was a labour of love, dedication and pursuit of excellence, not without risks and challenges.

Because of the exponential growth in the offer of streaming services during the last decade, the genre of the so-called “celebrity documentary,” i.e. a celebratory potrait/retrospective made in full cooperation with the subject, has gained a lot of traction and offered a new platform to filmmakers and documentarians to work on glossy portraits of beloved artists. However, it would be incredibly reductive to label John Williams as a “celebrity” of the film industry. While he certainly is part of the Hollywood machine that creates icons for the contemporary world, a figure like Williams has always been much above the mere cult of personality. At least until before the age of social media, film composers were notoriously “invisible” craftsmen of the film industry, staying behind the doors of their studios while pounding chords on the keyboard, or working with orchestras on the scoring stage. The only moment of public recognition was usually the Academy Award show, which offered an equal spotlight to both the very famous celebrities and the little known artisans. While very respected within the walled garden of the film industry, film composers remained virtually unknown people to the general audience for a long time and only a very few acquired the type of notoriety usually associated with Hollywood personalities. Literature and in-depth studies on the subject were also scarce for many years; aside from a few valiant historians like Jon Burlingame, Tony Thomas and Christopher Palmer, film music was looked down as a “minor” art by many music writers in academia and journalism. The rise of the internet in the late 1990s and early 2000s finally offered the chance to connoisseurs to extend and deepen their knowledge on the subject. This very website was born out of this need of trying to explore further and more deeply the reason why John Williams is above and beyond almost every other composer who worked in film, by providing a thorough and reliable documentation and offering a platform for an ongoing study on the composer’s work.

John Williams became the most well-known film composer in history for at least two reasons—he composed iconic and influential music for some of the most successful films of all time and became a well-known public figure during his stint as the music director of the Boston Pops (1980-1993). His indelible themes for such films as Jaws, Star Wars, Superman, Raiders Of The Lost Ark, E.T. were etched almost immediately in the hearts and minds of millions of moviegoers, but Williams became also the public face for film music for television audiences across the United States thanks to his appearances on the popular Evening At Pops tv program, conducting the Boston Pops and often featuring selections both from his movie scores and the classic Hollywood repertoire. As the years went by, John Williams solidified his reputation as the dean of American film music by composing remarkable scores for high-profile films and acclaimed blockbusters, but also acquired an even greater respect from established music institutions around the world, working with internationally acclaimed classical instrumentalists (Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma, Anne-Sophie Mutter), guest-conducting the most prestigious orchestras in the United States (and more recently also across Europe and Japan) and writing music for historical events like the Olympic Games and the Inauguration of the 44th President of the United States Barack Obama. So it’s not an exaggeration to state that the majority of the men and women walking on this Earth for the last 50 years have some personal memory or experience that they can associate with the music of John Williams, who in this regard has quite literally written “the soundtrack of our lives,” as the saying goes.

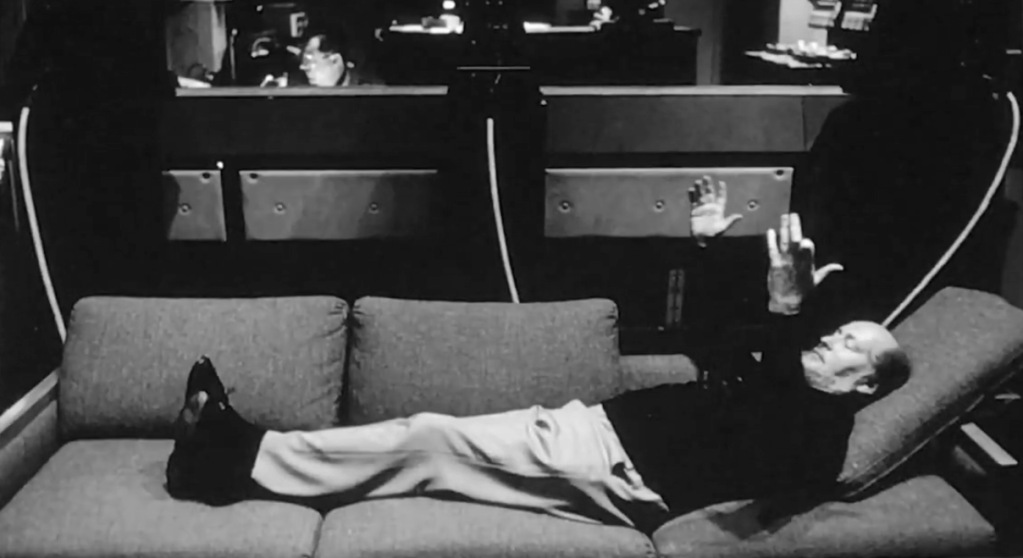

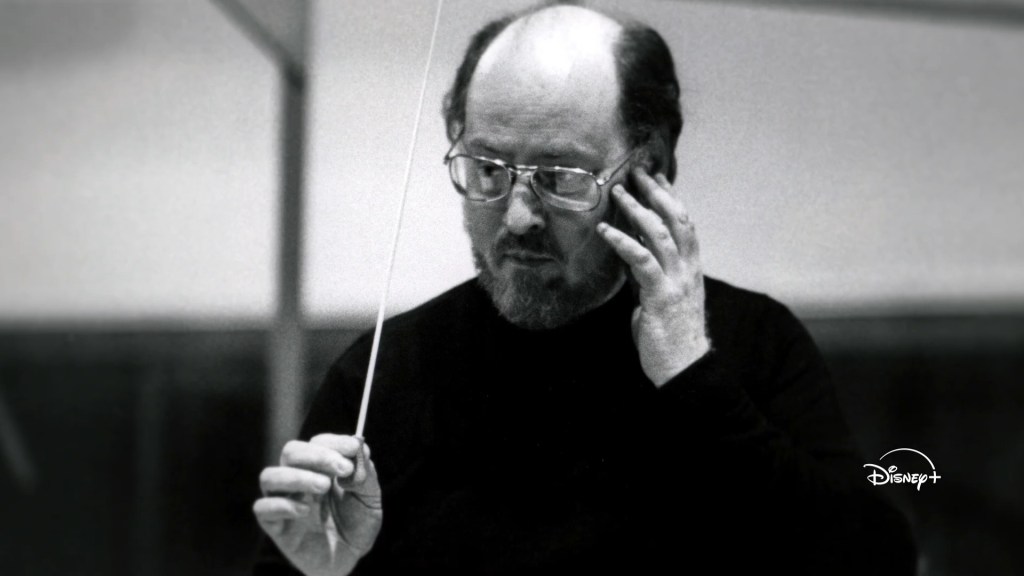

It’s with this incredible baggage of responsibility that director Laurent Bouzereau approached the subject of his film, aware that he was given the unprecedented task of creating something that should be fulfilling to both the connoisseur and the casual fan. The filmmaker could boast a privileged access to the artist—since 1994, Bouzereau has directed and produced behind-the-scenes documentaries for films directed by Steven Spielberg, often presented as bonus features of home video releases. Among these materials, there was always a segment or a specific featurette dedicated to the music of John Williams, with the composer himself offering commentary and recollections in front of the camera on his work for such films as Jaws, E.T., Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Indiana Jones, Jurassic Park and many others. These mini-documentaries offered glimpses to Williams’ creative process and often featured excerpts of exclusive footage filmed by Steven Spielberg himself during the recording sessions, showing the composer on the podium working with the orchestra. It’s the type of documentation that film score aficionados craved to see more of, to get a closer look to a creative process both mysterious and fascinating. In this regard, Bouzereau ammassed an astounding amount of insight on the composer, seeing him in action while crafting his own art and also becoming a trusted person for Williams himself when it came to documenting his work.

Bouzereau’s penchant for John Williams and film scores in general come from a real love for music—like many of his generation, he was raptured with the composer’s work already as a teenager when seeing Star Wars on the big screen in 1977. He soon turned into an uber-fan collecting soundtrack LPs and also a deep connoisseur of the whole breadth of the composer’s output. It’s perhaps this close encounter between the genuine passion as a fan (in the best sense of the word) and the attitude of the observer that made Bouzereau the ideal choice to tell the life story of John Williams for this new documentary. As he points out in our interview, the main goal was to create a piece that could be timeless and work as an entry door into the world of John Williams. “I made it also for the people who are not born yet,” says Laurent, hoping that the film will be looked at in the future as a sort of snapshot of a genius composer made during his lifetime. “What would we give to have something like this done at the time of Mozart or Beethoven?”, commented archival soundtrack producer Mike Matessino, who also served as Music Consultant for Music By John Williams.

It’s perhaps in both the simplicity and the straightforwardness of title chosen for this film, Music By John Williams, that lies one of the secrets of the success of the documentary, which has been immediately received with great acclaim and already started to collect awards—it was the opening film of the 2024 American Film Institute Festival and has just been honoured with the Critics’ Choice Award for Best Music Documentary. John Williams might not have had the tumultuos life full of unexpected events usually associated with highly creative personalities, but the genuine humbleness of his character, coupled with a total devotion to music, make him a relatable person to anyone who has an appreciation for his art and has been touched by his music. Those words, “Music By John Williams,” have always been a seal of guarantee when appearing either on the screen or on a movie poster, a promise that something exciting, memorable and touching was about to get to our souls through our ears. This is what this documentary wants to highlight and celebrate, and gets to do successfully.

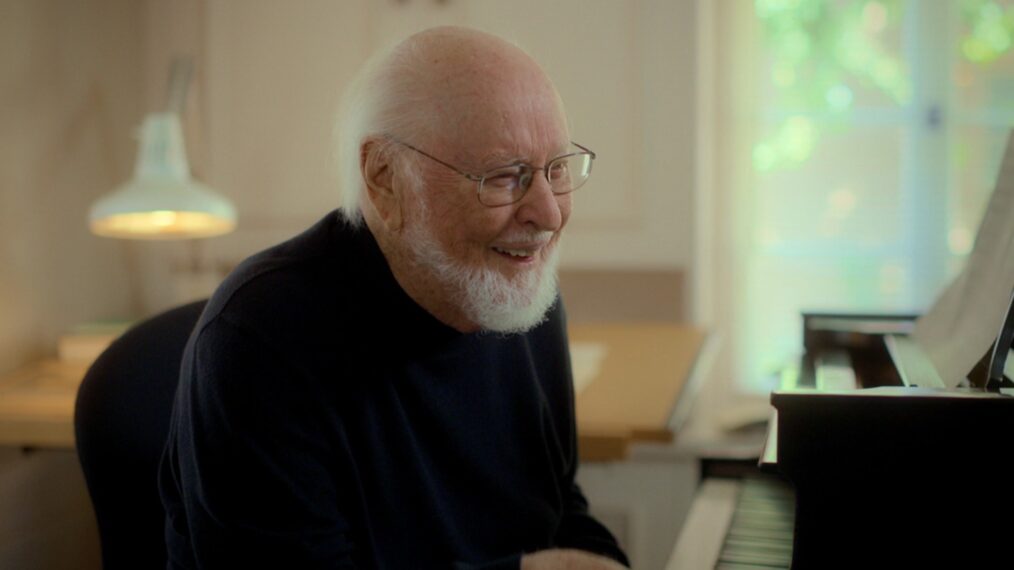

Many of John Williams’ closest and most important collaborators (Steven Spielberg among everyone else, of course) appear throughout the film to offer their own commentary and insight on the composer, adding important notes of both historical and aesthetical value. But it’s the presence of the composer himself speaking in front of the camera and going back to his earliest childhood memories that becomes the magnet for the audience, who finally can learn about Williams’ family life and early years as a young pianist. The composer is jovial and entertaining in the way he tells his own story, completely downplaying his ego and acknowledging the serendipitous nature of many of his career’s choices, but he also offers profound reflections about the nature of music composition—his explanation of the construction of the iconic 5-note motif of Close Encounters of the Third Kind is almost a synthesis of his aesthetic as a composer. Williams opens up and gets very personal when speaking about the untimely death of his first wife, Barbara Ruick, who passed away suddenly in 1974 and left the composer – father of three teenage children at that time – in a state of shock. Williams was about to enter into the phase of his career that would’ve launched him into stardom and the coincidence of the events offers an unexpected perspective with which we can now see and interpret his artistic path.

Bouzereau conducts the score of Williams’ story with swift and secure gestures, pointing on all the important milestones in the composer’s career and intercutting an impressive amount of never-before-seen archival material, including family photos and lots of behind-the-scenes footage of Williams working in the recording studio, using also a great deal of Steven Spielberg’s own home movies filmed during many of the scoring sessions of his films. It’s particularly exciting for anyone who has an interest into the creative process of film scoring to finally see these moments, as they show Williams working in detail with the orchestra. Bouzereau also highlights the importance that the composer had in offering the art of orchestral film music a new appreciation, mainly thanks to the success of Star Wars, but also through the work that Williams did at the helm of the Boston Pops, which led him to become a sort of spokeperson for film music appreciation and one of the most recognizable musicians in the world.

As Bouzereau himself admits, it’s almost inevitable to get celebratory when working on a profile of John Williams. His career has been punctuated by so many highlights, artistic peaks and successes that is almost natural to feel perhaps a bit overwhelmed when going through it during a retrospective like the one this film offers, from the Spielberg/Lucas blockbusters to the music for the Olympics, by way of Superman, Home Alone and Harry Potter, and his work as a conductor. But what Music By John Williams doesn’t forget to do is showing the human side of this legendary composer, whose talent is equivalent to his humility and grace. As with any artist who had a lasting impact in the imagination of millions, even billions of people, John Williams built his own legacy while constantly working and getting better at what he does. His music means a lot for entire generations not just because it’s attached to popular films, but because it’s intrisically great music that touches a deep chord inside all of us and makes us feel better human beings. This is the gift of John Williams and what Laurent Bouzereau’s film communicates so brilliantly.