John Williams turns 93 today.

Besides being a staggering age to reach for any mortal, ninety-three is an important number for John Williams fans: the year 1993 gave us both Schindler’s List and Jurassic Park, two bona fide masterworks—so stylistically and spiritually different, yet both containing such beautiful melodic heights and religioso depth. Jurassic Park was actually the score that awakened my own consciousness of who John was and what he did, so it will always hold a very special place in my heart.

Birthdays are a chance to reflect, and when February 8th rolls around we usually reflect on John’s work. But instead, I want to reflect on his life.

John was never keen on having a biography written about him, which was a major obstacle—both practically and emotionally—when I set out on my quixotic journey to do just that. There are several reasons why he objected to any kind of biographical project, but other than his long penchant for privacy the main reason he articulated was that he truly felt his life was unremarkable, that there was no real plot. Even I worried about this when I began discussions with my publisher about a potential book; should we focus more on the work and less on the man? His was not a life filled with tempest and fractured relationships like it is with many other great artists. There were no major scandals or vices or demons—no rise and fall from grace, no redemption arc.

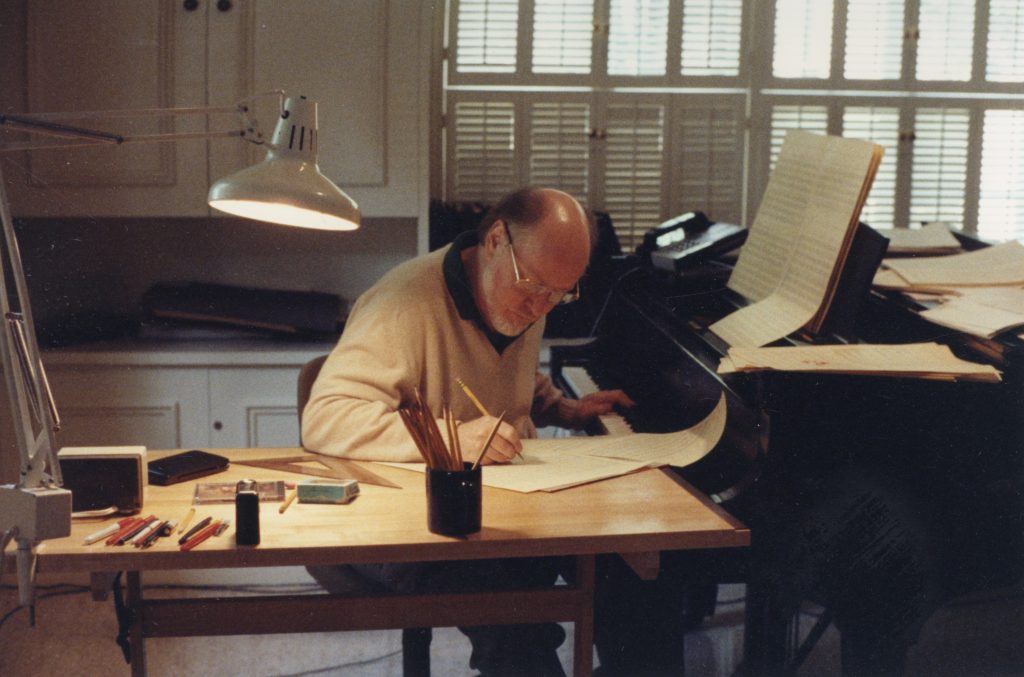

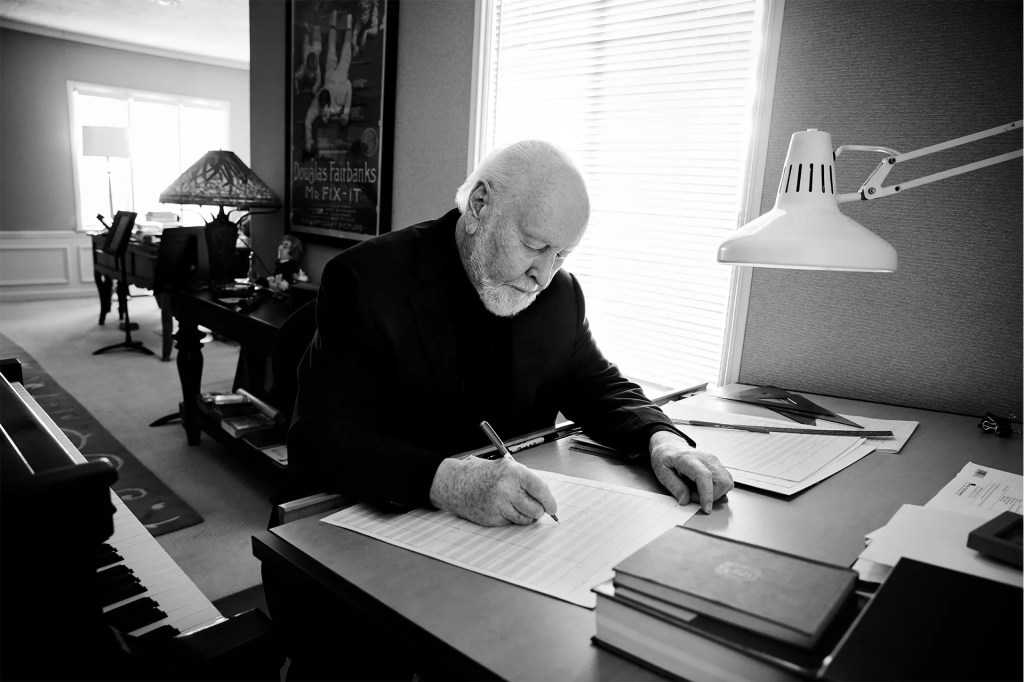

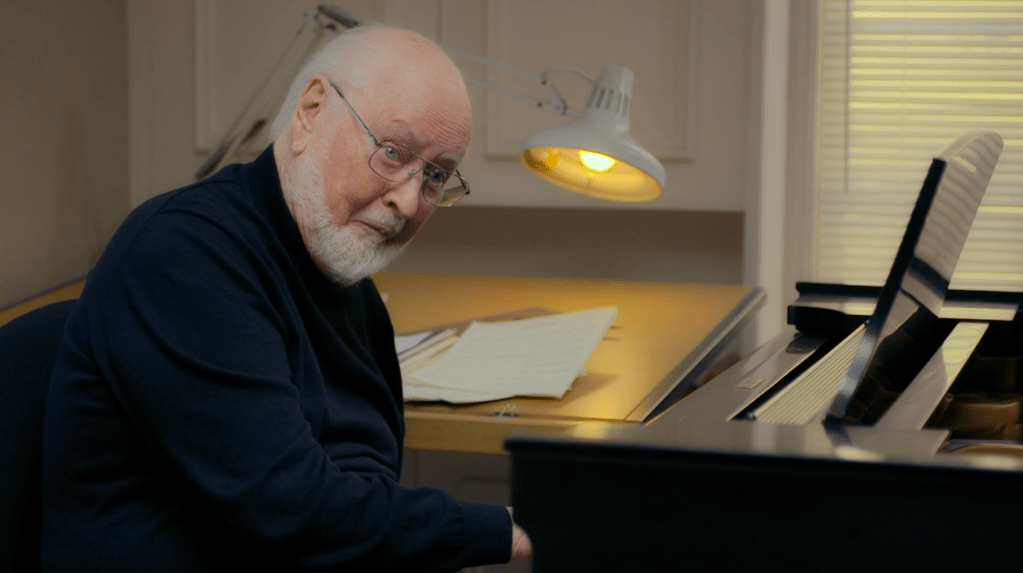

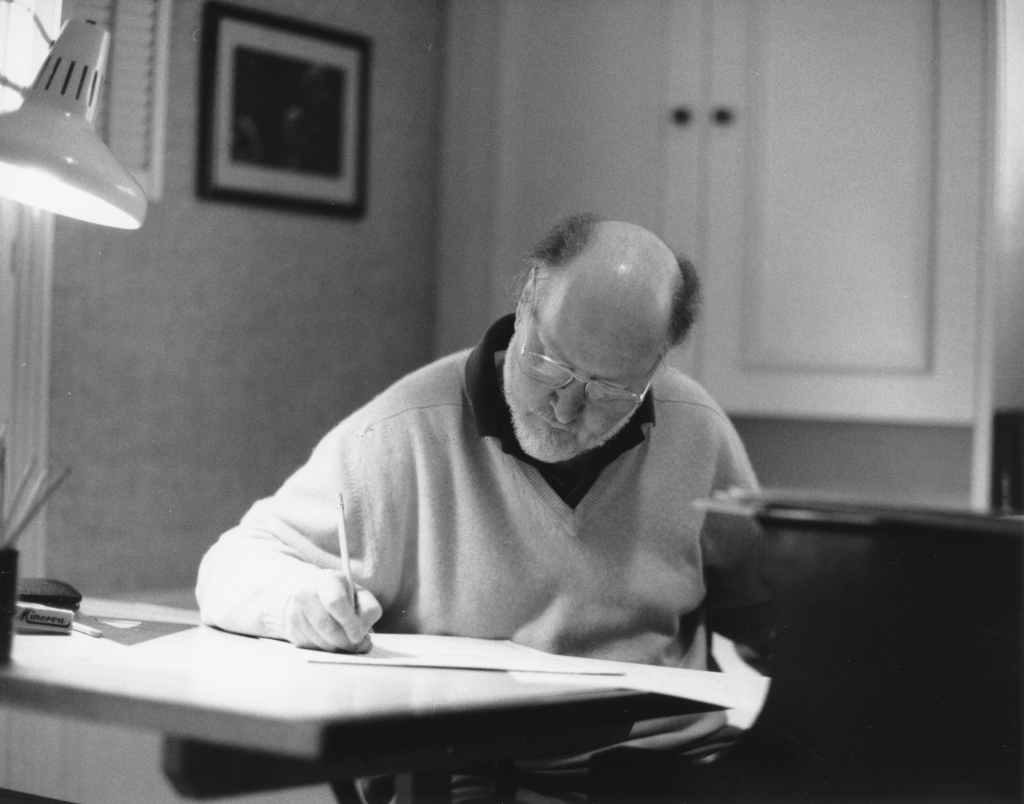

He is famously nice, never losing his temper or burning bridges. Everybody loves John Williams—but where’s the drama in that? He has lived, in his words, like a monk. He largely kept to himself and spent most of his waking hours writing music, conducting music, recording music, reading music. Obviously the music is what draws all of us to John Williams, and endless words could be written about it. Maybe the music was all there was to the story…

But as I began researching John’s actual life, interviewing the people who knew him (some as far back as high school), reading stories and archival interviews, and doing the biographer’s work of putting myself in the subject’s time, place, and shoes, I started to appreciate something about this seemingly “unremarkable” life story.

One of my all-time favorite movies is Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, which (as you undoubtedly know) is about an ordinary man named George Bailey—played by endearing everyman James Stewart—who doesn’t get to travel the world like he wanted to; he doesn’t even go to college. He stays in plain old Bedford Falls and makes one small sacrifice after another to save his little brother from drowning, to save his dad’s business, to bail out his neighbors, to support his growing family… and when it all goes south one day, he comes very close to ending his own life. But an angel shows George—by letting him experience an alternate reality where he was never born—just how rich and meaningful and beautiful his life has been. Which is something we, as the audience, already know, having spent the past 90 minutes seeing just how much George is loved, how many special and funny and sweet moments there were along the way, how decent he is, and how many lives he has touched for the good.

I think John Williams has had a similarly wonderful life.

So many people I spoke to for my book—musicians, friends, colleagues—commented on how he turns every conversation away from himself and toward them. He always asks his old Boston Pops musicians about their children, and he always treats their children with kind, genuine interest. Among his friends, John has a reputation for not just being nice but also drily funny, engaged, and thoughtful. People don’t just like John; they adore him.

“He was kind and sweet and dear and patient, and just pure goodness,” said Konni Corriere, Robert Altman’s stepdaughter, who was around John a lot when she was a teenager in the early ’70s. “You just fell in love with him because he was goodness personified. And I can’t think of anyone else I could ever say that about.”

“He’s got a lot of humanity in him, actually,” she added, “which I think comes out in his music.”

John has been quietly benevolent to a shocking degree. He has given countless millions to support orchestras all over the country, as well as the construction of concert halls. He has guest conducted many concerts for many American orchestras—often bringing Steven Spielberg with him—and donating his fee to the musicians’ pension fund. He has humbly refused to have any buildings or halls named after him on his beloved Tanglewood campus, where he absolutely deserves to have his own site alongside Bernstein Gate and Ozawa Hall (and Boston Symphony Orchestra has begged him to consider it). Instead, he initiated a project of commissioning sculptures for other important Tanglewood figures—Aaron Copland, Serge Koussevitzky, Leonard Bernstein, and Seiji Ozawa—and paid for all of it himself.

When a member of his L.A. studio orchestra lost her two infant children in a violent tragedy, John dedicated his beautiful “Elegy” to their memory—a gift she treasures to this day. When a film-loving high school kid in San Luis Obispo survived a horrible car crash which put him into a coma, John sent a personal letter and a copy of the E.T. soundtrack. “Who knows or can explain why things happen to each of us,” John wrote, jotting the notes for the E.T. theme at the bottom of his letter. “We can only hope we become better and stronger from the experiences.”

He is still as curious and excited to learn and create as he ever was, a fact that astounded the younger directors he has been paired with during the past decade. “There was this monumental statue in my head of John Williams, the master composer,” Rian Johnson told me. “And what broke out of that, once I got together with him and started working with him, was the childlike joy of invention, and the sharply tuned desire to break new ground—and to engage with every single story as if it’s the first score that he’s doing.”

And, he holds himself to the highest standard in everything he does. “He took everything seriously,” said the late Ken Wannberg, John’s longtime music editor and right-hand man. “There wasn’t anything that he didn’t give his utmost attention. … There’s nothing bad about John. And he’s so honest about his music.”

I’m not at all suggesting John is some kind of saint or holy figure. He is, in many ways, quite ordinary and completely human. He has had troubles and made mistakes. He has regrets. In spending so much of his life energy on creating music, he readily admits that he neglected relationships. He made sacrifices—sometimes selfish ones, but mostly in service to Music.

But his is a wonderful life, and he has made his individual world—and the whole world over—much better than he found it. Through his charity, his caring nature, and his artistic contributions, he has given so many millions of us a more wonderful life, too.

Oh, and by the way—his life does have a pretty great plot! John was surrounded by jazz and big band legends as a child growing up in New York in the 1930s and ’40s; he played with Shirley Temple on the Fox lot when he was a little boy; he went to high school with Susan Sontag and played piano with his dad’s orchestra at Columbia Pictures; he was such a remarkable young musician that his high school band was broadcast on the radio and attracted a reporter from Time magazine; he worked with Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly and John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock and Clint Eastwood and Harry Belafonte and Nat King Cole and Mahalia Jackson… and I haven’t even left the 1970s with this crazy list! He was friends with Roddy McDowall and Debbie Reynolds; he’s been kissed on the cheek by Audrey Hepburn. Count Basie played at his 50th birthday party.

I saw John at his home recently, and at one point I asked if he knew Shirley MacLaine. He had scored one of her films (we both laughed about the risible John Goldfarb, Please Come Home), and he also played piano on The Apartment score. He did know her—of course—but mostly through his first wife, Barbara. He told me he saw her not too long ago, and he said, “Shirley, it’s been a long time!” “John,” she said, looking very serious and without any irony, “there is no such thing as time.”

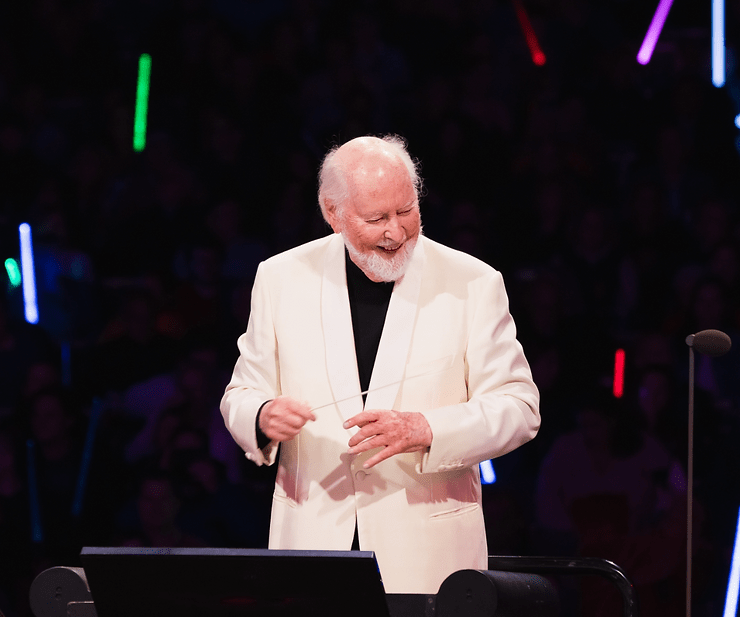

His life has been full of such surreal moments and remarkable relationships—of playing for multiple American presidents and other heads of state, meeting the Queen of the United Kingdom and celebrating the wedding of a Japanese princess, providing the soundtrack for the Olympic Games and many national spectacles, and turning old-fashioned orchestra music into a global phenomenon and wild concert energy that is typically reserved for pop idols.

This “ordinary” life has been anything but, and it makes for quite a yarn (if I may say so myself). But at the end of the day, and on the occasion of his 93rd birthday, I just want to say this: the more I learned about John Williams, and the more time I spent in his company, the more I admired the man. His unceasing quest for personal excellence and betterment and growth has been deeply inspiring to me. I want to be more like John Williams, which is not something I can say for many other artists whose work I admire.

It truly is a wonderful life.

John Williams: A Composer’s Life by Tim Greiving, the first English biography of Maestro Williams, will be released by Oxford University Press on September 1, 2025. You can pre-order your copy at OUP website:

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/john-williams-9780197620885

Watch the birthday tribute video produced by Maurizio Caschetto: