From the Merriam-Webster Dictionary:

Americana plural noun

1: materials concerning or characteristic of America, its civilization, or its culture broadly : things typical of America

2: American culture

3: a genre of American music having roots in early folk and country music

Among the many traits that define John Williams’ musical persona, a place of relevancy is occupied by the deep exploration of the so-called ‘American Sound,’ or that specific brand of musical vernacular also known as Americana. Throughout his works for both cinema and the concert hall, Williams has become one of the beacons of American music, creating his own unique version of the Americana genre, one that is intimately connected to the roots and the traditions of the country’s musical past on one hand, while on the other is rich with a youthful and vibrant look towards the future. This very characteristic side of the composer is perhaps, if not one of his most personal, certainly one of the most recognisable, showing the multitudes that his personality contains. Above anything else, it gives an opportunity to reflect on how successfully John Williams has navigated in the sometime troubled waters of late-20th century music and contributed immensely to the creation of a new symphonic/orchestral canon that remains consistent and relevant for today’s audiences. The fact all of this happened mostly thanks to (or in consequence of) his work for Hollywood films further illustrates how crucial “the Mecca of the movies” has been in helping to decode a shared musical language for the entire world.

John Williams’ investigation of the American sound began very early on, with some of his assignments for television in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, when he wrote music as part of the staff of composers at Revue Studios (the television branch of Universal Pictures) working on western shows such as The Tales of Wells Fargo and Wagon Train among others. But it was when he moved to film, especially in the mid-to-late 1960’s, that the composer began to flex his compositional muscles on projects that offered him a larger canvas. The Rare Breed and The Plainsman, both from 1966, are two westerns in which Williams remained close to the tradition of the classic sound of the genre as interpreted by Hollywood’s conventions, i.e. an expansive musical landscape rich with galloping rhythms, bold orchestral gestures and folk-tinged tunes. This style was first developed and brought to success by composer Dimitri Tiomkin in some of the most celebrated films of the genre like High Noon (1952), Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), Rio Bravo (1959) and eventually given an even more stirring and adventurous spin by composer Elmer Bernstein in such scores as The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Comancheros (1961) and The Sons of Katie Elder (1965). Tiomkin and Bernstein – for both of whom John Williams played piano for during his early years as a studio musician – are the noble fathers of the Hollywood Western sound together with Jerome Moross, whose landmark score for The Big Country (1958) was another milestone in defining the genre. As mentioned, John Williams’ early incursions in the genre were well within in the Hollywood tradition, showing a robust understanding of the conventions of this style applied to the film narrative.

Hollywood’s interpretation of the sound of the “Old West” was parallel to what some of the most distinguished American composers of art music were discovering and exploring in their works for the concert hall throughout the 1930’s and ‘40’s. Aaron Copland is universally considered the true progenitor of Americana in symphonic music—even though he never purposefully set out to create it in the first place. In fact, Copland’s early works were characterized by the same modernistic and sometimes abrasive harmonic language of early-20th century European music (Copland was pupil of famed French composition teacher Nadia Boulanger). However, when he approached forms of applied music like radio, theatre, ballet and film, it came the necessity to reach a wider and perhaps less schooled audience. Therefore Copland found a new voice using more traditional harmonies, like the predilection for open fifths, and going back to the roots of traditional American folk-songs and hymns of the previous century. His seminal works Billy the Kid (1938), Rodeo (1942) and Appalachian Spring (1944), all written for ballet, form a tryptich of the quintessential style that people would then associate to the term “Americana”, with its vivid evocation of wide open spaces, pastoral life, pioneering exploration and the vastness of American landscapes.

This vernacular would also define such influential film compositions by Copland as Our Town (1940) and The Red Pony (1949), universally considered as cornerstones of the Americana musical lore. Copland was not alone in this search for an authentic and recognisable “American sound”—his slightly older colleagues Virgil Thomson and Roy Harris were also writing works along the same lines, going back to hymn tunes and folk-songs as the basis of their compositions, creating a style that could be directly related to the “American heartland” and thus being the basis for an age of new orchestral music that could be identified as uniquely American.

The fact this was happening in the years between the Great Depression and World War II could be seen as an interesting parallel to what was going on in Hollywood at the same time, where a troop of European, conservatory-trained emigré composers was literally inventing the sound of movies—including the western genre—and thus creating a relatable musical language for audiences across the world. If early Hollywood composers were mostly looking at the tradition of the great orchestral literature from Europe, especially from the late-19th century repertoire in the first place, the success and popularity of the Americana vernacular would soon become an inescapable reference point, especially for such composers as Bernard Herrmann and Hugo Friedhofer, whose seminal scores respectively for The Devil and the Daniel Webster (1941) and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) are imbued with a distinct American sound. In subsequent decades, it would be composers like Jerry Goldsmith, Elmer Bernstein and John Williams who would’ve taken up the mantle and explore even deeper the style of Americana in film scoring.

John Williams’ career as a film composer began when Hollywood’s glory days were winding down and the sound of the movies was definitely starting to be contaminated with and influenced by the pop music of the era, be it either light jazz or the first wisps of rock ‘n’ roll. Such stylings characterize many of Williams’ early film scores too, especially “screwball” fare like Bachelor Flat (1962), John Goldfarb, Please Come Home (1965), Not With My Wife, You Don’t! (1966) among others. The classic Hollywood orchestral sound however didn’t completely vanish and, whenever the project required it, Williams swam into that pool with same confidence, as demonstrated by some of his early scores for dramas like the World War II movie None but the Brave (1965), directed by none other than Frank Sinatra. As assignments got bigger and more prestigious, the composer used his polyedric skills with class and ease, as well as a stunning breadth of style and knowledge of different genres.

It was in 1969 that an important occasion to weave into the fabric of American music presented itself to the composer, when he signed to compose a replacement score for The Reivers, a film directed by Mark Rydell based on William Faulkner’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, a coming of age story set at the turn of the century in rural Mississippi. The film offered the composer a canvas upon which he could display a great array of colors, all related to authentic American vernacular, from old-time music to the folksongs of Stephen Foster, but also bluegrass, early jazz, blues and Copland-esque orchestral Americana, all perfectly wrapped up by Williams’ innate sense of drama and musical storytelling. As writer John Takis observes, “The sound [Williams] created for The Reivers proved an ideal match for Faulkner’s blend of playful humor and vividly drawn prose, conjuring the warm glow of an “endless summer” as experienced by a child on the cusp of adolescence. His melodies are colorful and long-lined, enlivened with the intricate contrapuntal writing that was already a signature element of his voice.” In addition to getting him the first Academy Award nomination for original music, the score proved to be a signpost for the composer’s subsequent career, as it grabbed the attention of a then young up-and-coming director named Steven Spielberg, who was so impressed by the score that he promised himself that if would’ve ever had the chance to direct a feature film, he would’ve had the composer of The Reivers write the score. This indeed happened in 1973, when Spielberg directed his debut theatrical feature The Sugarland Express and John Williams composed the music for, igniting a historical collaboration that would’ve continued for the decades to come. Perhaps also for this reason, Williams kept showing a particular affection for this score and repurposed it as a concert suite for spoken word and orchestra which he premiered during his debut concert as the music director of the Boston Pops in April, 1980, with Burgess Meredith reprising his role as the original film’s narrator. “I just love The Reivers,” noted Williams in a 2009 interview with conductor Lucas Richman. “Mark Rydell directed the film beautifully and it starred the late Steve McQueen, who embodied so many of these kind of characters of romantic, let’s say, 19th century Americanism that’s so beautifully depicted in the film.”

The 1970’s were the moment where John Williams’ career started to really take off and there came several film projects that led him to explore even further the American sound. Director Mark Rydell gave Williams another shot with The Cowboys (1972), a western starring Hollywood’s cowboy icon John Wayne as an aging ranch owner who instructs a herd of young schoolboys to become drovers. The film is fully rooted in the tradition of the genre and Williams answers the call with a symphonic score rich with western stylings and the modalities of Americana. The youthful energy of the main characters is portrayed with a rip-roaring “cowboy” theme in the classic Copland tradition, while Wil Andersen (John Wayne) is accompanied by a nostalgic theme that opens with a perfect fifth interval – the classic “hero” figure in music – before going into a more wistful territory, perfectly capturing the crepuscular side of the main protagonist and his fatherly demeanor with the kids (it’s interesting to note that Williams would use similarly contoured themes in subsequent films featuring American father-like figures, i.e. teacher Pat Conroy in Conrack, Kal-El’s earthly father Jonathan Kent in Superman and John F. Kennedy in JFK). In The Cowboys, Williams captured something deeply connected to the roots of the story, as if writing to the overall western myth rather than just accompanying the film. As Mike Matessino observes in the liner notes for the deluxe soundtrack album, “there is the expected nod towards Copland (a Rydell favorite) but Williams, in his unique voice, does exactly what he would later accomplish with the likes of Superman and Dracula: he transcends the story at hand and encapsulates an entire mythology. Our collective memory and images about the Old West are somehow summarized definitively in The Cowboys.”

The following years gave Williams an almost continuous string of films in which he was able to explore different tones of his Americana voice, sometimes in its classic orchestral vest, others instead using a more intimate and gentle approach. His work for the adaptation of the film musical based on Tom Sawyer (1973) belongs to the former—Williams takes the Sherman Brothers’ songs and melodies, already written with folk-tune inflections, and gives them flavorful Copland-esque orchestral dressing, with upbeat, dance-like ornamentations and the canonical colours of such country instruments as harmonica, guitar and banjo.

The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing (1973) is a western that strips off most of the traditional mythology of the frontier for a grittier and more violent approach, in the wake of films like The Wild Bunch (1969) and Soldier Blue (1970), and Williams does the same with the music—the score never plays too much the western setting (save for the occasional Copland-like moments), but goes for a subdued approach featuring a small ensemble, with prominence of solo playing by harmonica, acoustic guitar and trumpet. Williams provides a tuneful bluesy main theme with a contemporary beat, relating to the outlaw protagonist Jay Grobart (Burt Reynolds) and the love for his late Indian wife Cat Dancing, but as the story goes it morphs into the growing feelings for Catherine (Sarah Miles), the young lady who falls in love with him.

A similar subdued vein is also found also in two projects from 1974, Conrack (directed by Martin Ritt) and the aforementioned The Sugarland Express. Neither is a western or a story set in the lore of American foundation, but each gave Williams the chance to further refer to elements of the American musical vernacular—rustic and folk-like in the case of Conrack, more bluesy and country-inspired for Spielberg’s film. Both scores intervene in the respective films with a gentle touch and feature lovely writing featuring solo harmonica and acoustic guitar, two instruments that harken back to the roots of American music.

The Missouri Breaks (1976) by Arthur Penn is another atypical western which eschews possibly all of the conventions of the genre. It’s driven by the lunatic performances of both Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson and an overall hallucinated feeling throughout the narrative. John Williams accompanies the film with sparse scoring using a contemporary country/blues vein, again with lots of solo harmonica and acoustic guitar, far removed from the sprawling orchestral Americana heard in The Cowboys or in the more expansive cues of The Reivers, but instead featuring one of the smallest ensembles in his oeuvre (six players, including the great harmonica player Tommy Morgan, also present in The Reivers, The Cowboys, Conrack and The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing), which gives an improv-like quality to the music; quivering lines for electric bass and harpsichord augment the off-kilter feeling of the film. It’s nonetheless an interesting element that fits perfectly in this line of projects of the 1970s where Williams went through several permutations of the Americana genre.

After the humongous success of Jaws, Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, John Williams became the superstar of film composers and his name synonymous of the return of the classic symphonic style that was considered out of fashion throughout most of the 1960’s and ‘70’s. Superman (1978) too belongs to this series, but it also offered Williams a chance to visit again the territory of purest Americana since The Cowboys. For the scenes set in Smallville, Kansas, the composer paints some heartfelt musical pictures of noble American sound, with pastoral cues perfectly matching both the gorgeous Andrew Wyeth-inspired imagery by Geoffrey Unsworth and the inner feelings of growth and search of meaning of young Kal-El/Clark Kent. When writing this sequence, Williams said he thought of “his lineage and his youth and the expanse of the country, which was beautifully photographed, to contrast with the extra-planetary aspects of his life.” In addition to being related to the main Superman theme, the perfect fifth interval that opens the Smallville theme ties it to the tradition of the Americana harmonic language and therefore puts the character as part of a specific mythology.

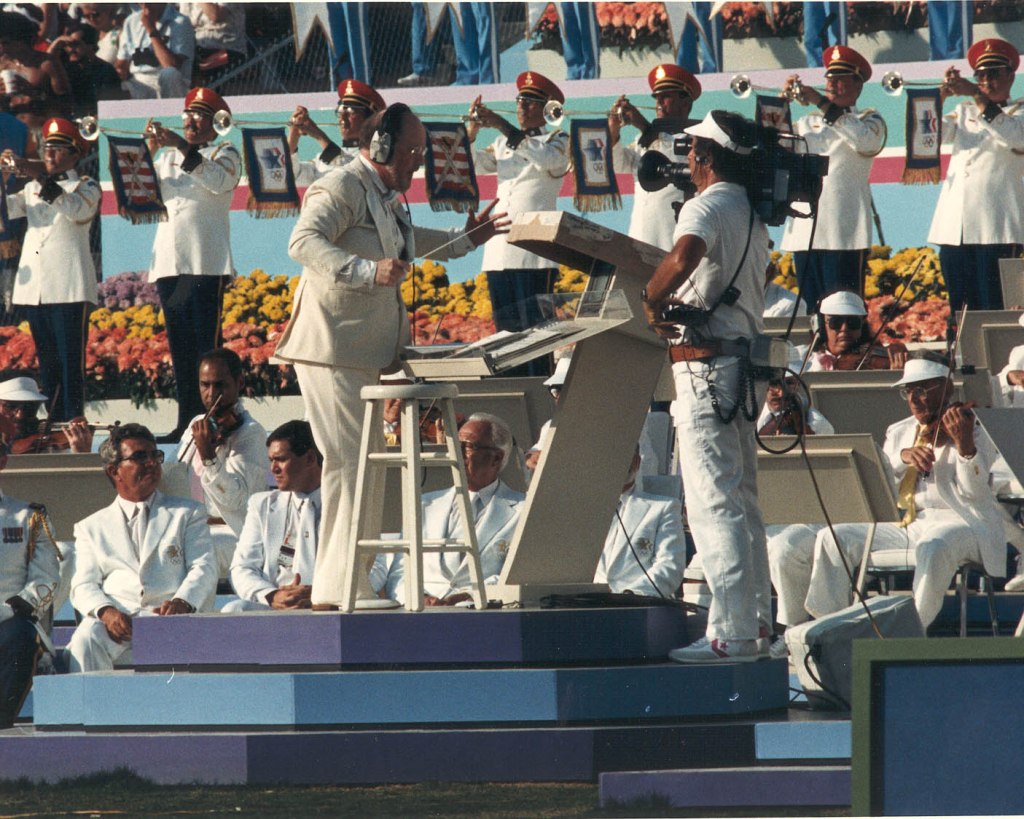

Throughout the 1980’s and the 1990’s, John Williams became even more popular thanks to the immense success of the films he wrote the music for, but also after accepting the role of music director and principal conductor of the Boston Pops, a post he maintained from 1980 to 1993, and after which he was named Laureate Conductor. This side of his musical life brought his fame to a new level – also thanks to the multiple appearances on the Evening at Pops tv show aired by PBS during his tenure – but several non-film commissions also contributed to make him as “America’s Composer.” Works such as “Olympic Fanfare and Theme” (composed as the official theme for the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles), “Liberty Fanfare” (written for the ceremony of re-dedication of the Statue of Liberty in 1985), “Olympic Spirit” (part of the music package for the NBC broadcast of the 1988 Olympiads in Seoul, South Korea), but also his opening music for the NBC News (aka “The Mission,” 1985) gave Williams the chance to both reach a wider audience and to explore a jubilant vernacular rich with fanfares and heraldic writing for events and moments of collective celebration in American history. This can definitely be considered another current of his Americana voice, one that joyfully celebrates the spirit and the inner values of patriotism while looking with unbridled optimism towards the future. Williams composed several of this type of occasional ceremonial pieces (“Celebration Fanfare,” “Celebrate Discovery,” “Hymn To New England,” “America, The Dream Goes On,” “Summon the Heroes” to name a few), creating an ever-growing repertoire of uplifting American music worth being included in a catalogue that contains popular works by Copland, Leonard Bernstein and George Gershwin. The style has been often described as “Williams-esque,” or “Williams-ian,” whenever other composers approached this type of commissions with a similar vein, a sign that Williams’ music has seeped into the consciousness of the subsequent generations and became part of the fabric of Americana.

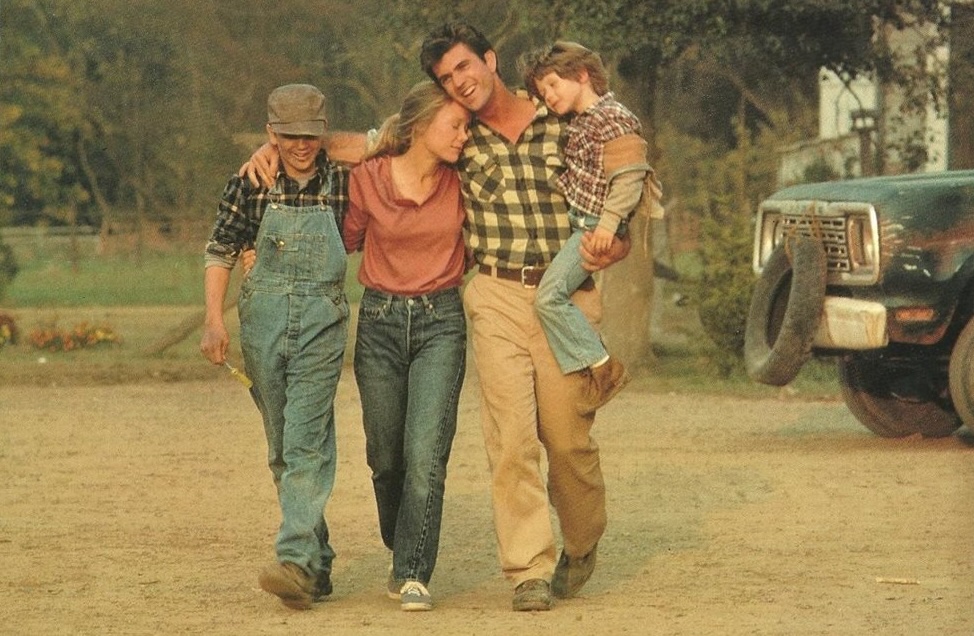

Meanwhile, movies too continued to present Williams occasions for exploring the different facets of Americana. Director Mark Rydell assigned him the score for The River (1984), a contemporary drama about the struggles of a farm family in Tennessee trying to keep its farm from going under in the face of bank foreclosures and floods in the river valley. The rural setting inspired Williams to write a score imbued with both American pastorale–type of cues for full orchestra and more rustic, country-flavoured pieces featuring duets for acoustic guitar and flute. There is also a bluesy love theme for solo trumpet that gives an added layer of Americanism to the score—the music relates to the human drama of the characters and connects them profoundly to the land, thus creating a strong feeling of attachment to the environment in which they’re living.

SpaceCamp (1986) gave Williams the chance to apply his uplifting, fanfaric style to a movie score—the composer fills the soundtrack with hefty doses of his own American sound, perfectly capturing the sense of wonder and exploration felt by the crew of young astronauts throughout their adventure in space. Williams’ score skyrockets into the stratosphere with jubilant brass and lyrical strings, accompanying the story with an irresistible sense of joy and optimism. “I’ve tried to express the exhilaration of this adventure in an orchestral idiom that would be direct and accessible…speaking directly to the “heart” of the matter,” commented Williams. In fact, his music for SpaceCamp celebrates the pioneering spirit that distingushed the American space program and the efforts of NASA in the exploration of the next frontier.

At the end of the 1980s, Williams initiated a very fruitful collaboration with director Oliver Stone that would produce three very distinct and unique works, but related by their connection with the history of modern America.

Born On The 4th of July (1989) carries the harrowing drama of private Ron Kovic (Tom Cruise) with a powerful score describing the American Dream dying among the horrors of the Vietnam war, dominated by a haunting trumpet solo (performed by Tim Morrison) that sounds like the cry of a dying soldier, followed by elegiac writing for strings and finally opening up with a “homecoming” theme for Kovic’s connection to his roots and the proudness for a newly found purpose and mission in his life.

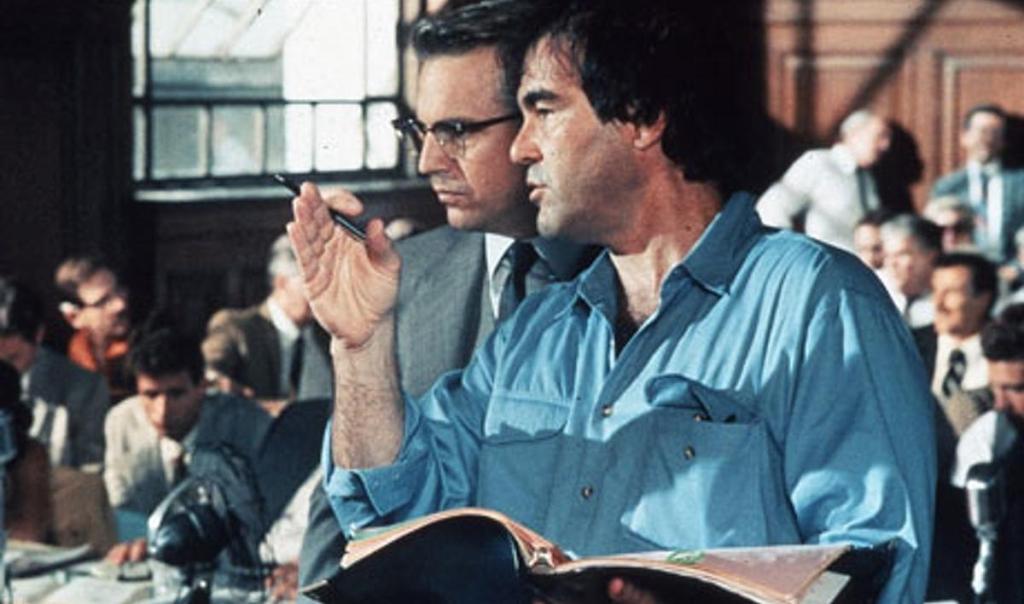

For JFK (1991), Williams composes one of the most exquisitely American themes in his oevure, both an ode to the assassinated U.S. President and to the firm ideals of district attorney Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner), again featuring a resplendent trumpet solo by Tim Morrison and conveying a moving feeling of justice and righteousness; however, the score is haunted by darkness, with obsessive repetitive motivic cells and an unusal array of electronic sounds to underline the conspiracy beneath. Williams also provides a funereal lament for solo horn and strings mourning the passing of true American values.

A similar journey into darkness defines the third and final Stone/Williams collaboration, Nixon (1995), in which the director’s flamboyant, operatic portrait of the controversial U.S. President is amplified by a largely brooding score featuring twisted, sinister progressions that almost sound like Americana turned on its head: the ultimate musical depiction of the Dark Side of America—until then, that is. Williams finds a few spots of serenity and quietness even in such ominous landscape, with hymn-like music for the scenes of Richard Nixon’s youth in Whittier, California.

In the late 1990s Williams worked on a series of projects in which he returned to the classic American sound that would become an even more pervasive element of his musical life. In 1996, it was director John Singleton who gave Williams the unique chance to compose an Americana score with strong connections to music rooted in the history of black people: Rosewood, a harrowing drama about the real story of an oppressed Black community in a small town in Florida in the early 20th century, is accompanied by Williams with a touching score that pulls together the music of both the black and the white people: the former with authentic spirituals and gospel-inspired cues (for which he also provides powerful lyrics); the latter with country and bluegrass moments for harmonica and solo guitar, harkening back to early-20th century street folk bands. Williams here revisits some of the musical climate that warms scores like The Reivers and The River, but adds also a touch of quiet heroism in the music associated with the main character of Mann (Ving Rhames), giving him a noble theme for horn and strings also tinged with “blue note” colorations.

The inspiration of Black-rooted music would also return a few years later (2000), when he wrote Three Pieces for unaccompained solo cello dedicated to Yo-Yo Ma (one of which is titled “Rosewood,” but doesn’t have any relationship to the film score), where Williams expresses “the vernacular manner of musical speech and rhythmic inflection that characterize this most important “root-source” of American music.”

It was however Steven Spielberg who brought John Williams back to wholesome Americana with a series of projects dealing with crucial events of the American history, starting with Amistad (1997) – a tale of horror and pain, this time about slavery and freedom, in which Williams brings together African-tinged writing for the group of slaves (featuring percussion, chorus and ethnic winds) and patriotic music inspired by the Quakers spotlighting solo trumpet for scenes involving U.S. President John Quincy Adams and the group of brave attorneys defending the Africans “to highlight the aspects of this ennobling and heroic fight,” as the composer noted at the time. The score is capped by a jubilant piece for mixed choir singing verses in Mende (the African dialect spoken in the film by the natives) adapted from a poem by Bernard Dadié, under which an orchestra augmented with a large ethnic percussion section sings along the joyful anthem which musically represents a renewal between African roots and American ideals.

Saving Private Ryan (1998) followed immediately after and brought Spielberg and Williams to revisit the World War II era after Empire of the Sun and Schindler’s List, but in this case with a story of courage and sacrifice made by U.S. soldiers on the altar of freedom. The shockingly brutal and realistic war scenes are left without any kind of musical accompaniment, but only with the almost unbearable sounds of warfare. When Williams’ score intervenes is to offer respite and reflection on what we’ve just seen, with long, mournful adagios featuring a ghostly tattoo of militaristic colors and moving solos for trumpet and french horn, quietly honouring the memory of the combatants and offering them a sobering musical memorial. Again, Williams evokes the nobility of vintage Americana, but adds his own personal inflections, especially in the elegiac piece for chorus and orchestra heard in the end credits, a wordless requiem for the fallen soldiers.

At the turn of the millennium, Williams worked on a project that again defined his strong relationship to the American culture and its musical embodiment. The documentary-with-live-performance The Unfinished Journey (1999, a.k.a. American Journey), produced by Steven Spielberg for the Y2K celebrations in Washington D.C. spearheaded by U.S. President Bill Clinton, gave Williams the chance to sort of encapsulate almost all of his Americana threads in one single work that celebrates the indomitable spirit of the country. The work returns to key events of 20th century United States “with a series of tableaux that could be dealt with individually,” said the composer at the time. The performance features the words of Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr. set to a series of film montages accompanied by patriotic fanfares, noble adagios, delightful scherzos, all tied up with quintessential Williams gestures. “There is so much for Americans to be proud of, even in some of our misfires and our outright failures,” commented the composer. “We wanted to look at the good things and the bad things and frame them in such a way as to take heed, and to take heart at the same time, and have this be an uplifting experience.”

Similarly, the Roland Emmerich-directed American Revolution epic The Patriot (2000) presents a conjuncture of Williams’ earnest Americana voice as heard in Amistad and Saving Private Ryan and his stirring fanfare-laden writing usually associated with the celebratory non-film works: if the former is used to support the noble values of main hero Benjamin Martin (Mel Gibson), the latter creates a rousing sense of revanche for the final conquering of freedom and independence. The score also offered Williams the chance to write a love theme inspired by 18th century folkloric material of the Appalachian region, splendidly rendered with a rustic fiddle solo by Mark O’Connor, which the composer described as “a pure sound that is inescapably attached to that particular geography and that period.”

Throughout the 2000s, John Williams kept incredibly busy despite his age with both film and non-film work, cementing his status as “the Voice of America” with some prestigious commissions like the grand opening of Los Angeles’ Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2003 – for which he wrote the intricately dense concert work Soundings – and the Inauguration of President Barack Obama in 2009. This last piece (“Air and Simple Gifts”) was another trip to the Americana well, this time for a small ensemble (violin, cello, clarinet and piano), in which Williams pays dutiful homage to Aaron Copland (Obama’s favorite composer) by quoting the Shaker hymn known as “Simple Gifts” (used in Appalachian Spring) and crafts a piece full of hope that is both familiar and unpredictable. “Befitting the occasion, it seemed like music of possibilities, with more to come,” noted the New York Times music critic Anthony Tommasini at the time.

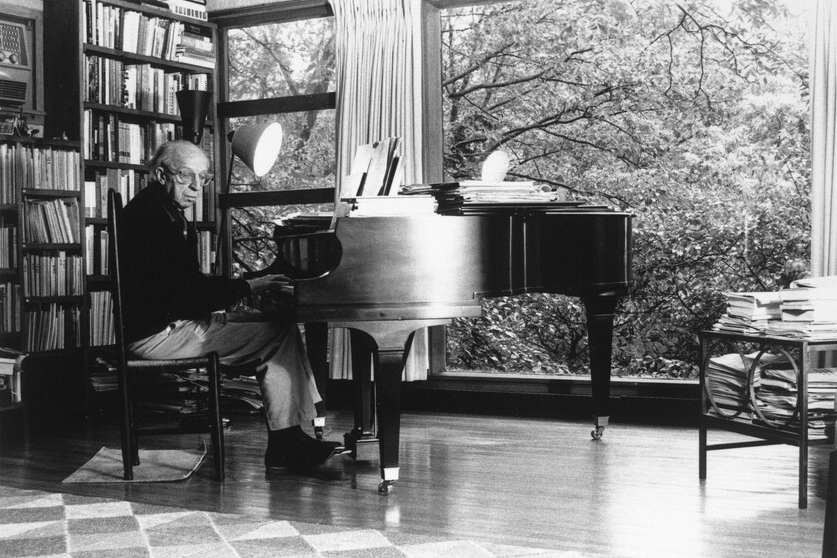

U.S. Presidents kept returning also in Williams’ film oeuvre—in 2012 Steven Spielberg finally brings on screen his long-gestated biopic on Abraham Lincoln. Based on Doris Kearns Goodwin’s tome Team Of Rivals, Lincoln chooses to focus on the President’s last months of his life, recounting the uphill battle to approve the 13th Amendment, i.e. the government law that would’ve abolished slavery, and all the political machinations that went behind the scenes to get it finally passed by the Congress. In a film packed with dense dialogue Williams enters into the field to contribute quiet musical reflections filled with rich and warm 19th century Americana colours. It’s a very consonant, tonal work where the composer writes hymn-like themes filled with both nobility and restraint, featuring inspired solo writing for several instruments (piano, horn, trumpet, bassoon, clarinet, fiddle), reflecting the human qualities and the overall character of a monumental figure that occupies a landmark role in the history of the United States.

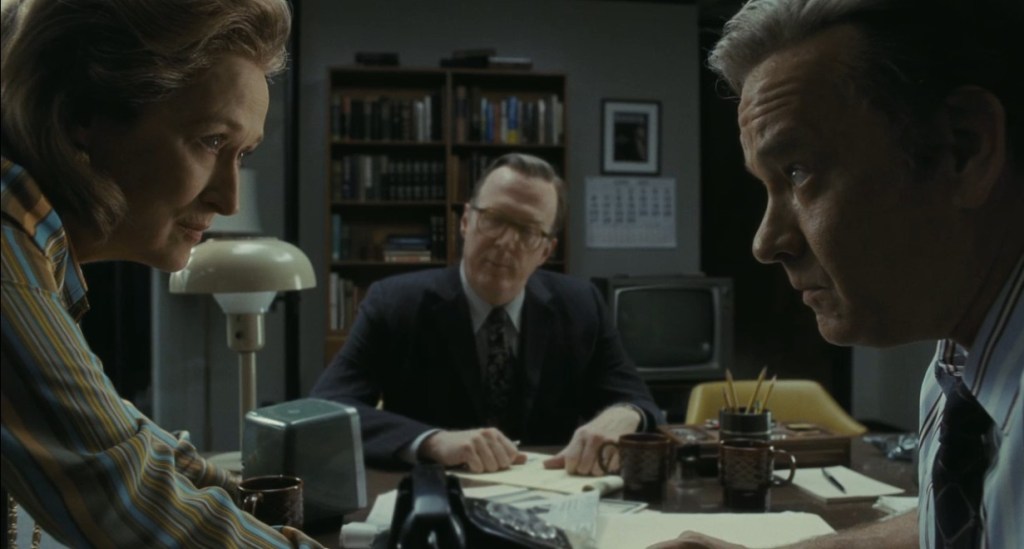

Shades of Americana-tinged writing are found also in Steven Spielberg’s The Post (2017), another slice of history of the United States, in this case from a more recent past—the scandal of the Pentagon Papers and the beginning of the end of the Nixon administration. Despite most of the film is accompanied by a minimal, unobtrusive score, in the final moments Williams’ music takes a leading role, sustaining the resolution of the drama with noble orchestral passages and exquisite solos for piano and horn brimming with quiet patriotism and, as Steven Spielberg described this style of Williams, “noble sobriety.”

One may hear a small hint of Americana in the touching “mother and son” theme in Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans (2022), especially in its reading for solo acoustic guitar heard over the end credits of the film, almost like a drop of perfume that scents the atmosphere. It definitely makes sense to think that John Williams may have wanted to pay a tribute to the most sincerely American film director of our age, one who helped define the identity of modern American cinema together with his inseparable composer friend… and whose music he discovered more than 50 years before thanks to one of his first outings in the Americana style, a score which Spielberg described as “a real American score.”

Perhaps we can add, without the risk of being proved wrong, that John Williams is a real American composer, one that has shown deep love and untarnished respect for his country on countless occasions and who truly has helped create the ‘American Sound’ as we know it today.

Special thanks to Mike Matessino, Tim Burden and John Takis.