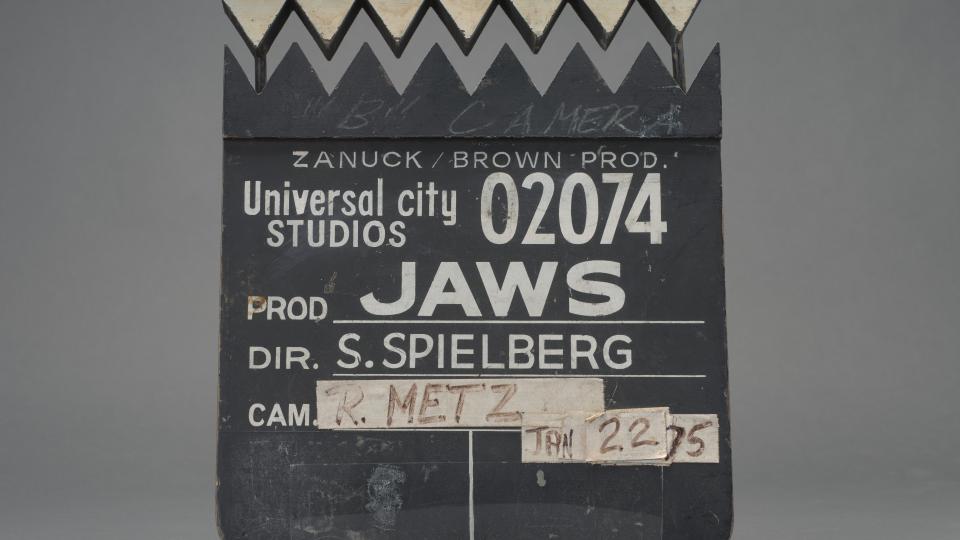

On June 20th 1975, the film Jaws directed by Steven Spielberg was released in movie theaters across North America in 464 screens after a massive marketing campaign that made the movie an event not to be missed. It’s well known what happened right after, the seismic shift it represented for Hollywood’s film industry and for the career of its director. Jaws has turned 50 on June 20th 2025 and Universal Pictures has set up a whole slew of activities to celebrate the milestone anniversary, including a theatrical re-release, an anniversary edition on Digital and Blu-Ray, a brand-new documentary by Laurent Bouzereau, an exhibit at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles and a massive remastered reissue of the film’s soundtrack on vinyl, digital and CD.

It’s almost scary to think that Jaws has been in this world for half a century already, but its everlasting impact makes us feel like it always existed, to the point that – as it’s often said of any true cultural milestone – it’s now virtually impossible to imagine a world without Jaws. The success of the film, both financially and creatively, is inextricably tied to its indelible musical score composed by John Williams and it feels almost a duty for a website like this to properly celebrate such a wonderfully round anniversary, especially considering the watershed moment this film represented for the career of the composer. But it’s very hard to add something truly significant that hasn’t been already well expressed or discussed by much finer minds than this writer’s over the course of these 50 years. In 2020, on the occasion of the film’s 45th anniversary (it seems now mandatory to celebrate film anniversaries every quinquennial), we published an essay offering a bird’s eye view on the making of John Williams’ classic score which contained a fairly comprehensive assessement of the music in both its historical and aesthetic values. For the 50th anniversary, the essay has been thoroughly revised and expanded, to also reflect the new remastered soundtrack editions produced by Mike Matessino. So, let’s take another deep dive to celebrate one of the true all-time masterpieces of film music.

Prelude: The Genesis of Fear

What are the odds that just two notes a semitone apart would become synonymous of terror, fright and sheer primal fear? This wasn’t Steven Spielberg’s idea when, back in the first months of 1975, he was about to listen to a demo of the main theme for his new film Jaws played on the piano by his composer of choice John Williams:

“When [John] finally played music for me on the piano, he previewed the main Jaws theme… I expected to hear something kind of weird and melodic, tonal but eerie, [something] of another world, almost like inner space under the water. And when he played instead with two fingers on the lower keys [hums] dun-dun… dun-dun… dun-dun-dun-dun… at first I began to laugh. I thought he had a great sense of humor and he was putting me on. And he said, “No, that’s the theme to Jaws!”. I said “Play it again”, and he played it again, and again… and suddenly it seemed right. John found a signature for the entire movie.” 1

Before exploring why such a deceptively simple musical solution became an iconic element able to define the entire film, it’s important to give some context on the genesis of this movie and its musical score.

The history of the making of Jaws has become the stuff of legend. Any serious movie fan has probably immersed into the sea of many stories that characterized the troubled production of the film through various books, articles and documentaries since basically the release of the film itself. Carl Gottlieb, the film’s credited screenwriter, kept a detailed journal throughout the production which would later be published as a book called The Jaws Log. Like the movie, it became a best-seller and one of the true Bibles for movie fans. Rarely the making of a film turned as exciting, suspenseful and unpredictable as the story depicted on screen: Gottlieb chronicles the various ups and downs, twists and turns, joys and sadnesses the whole crew experienced during the production of Jaws with down-to-earth honesty and even a dash of dry humor. Among the issues the crew faced during filming were the now-notorious technical bugs that plagued the huge mechanical shark built by special effects wizard Bob Mattey (the man responsible for the legendary “Giant Squid” in Disney’s 1954 classic 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea). Such big piece of expensive prop was a true novely in terms of mechanical effects and the crew was unprepared to deal with a complex hydraulic machine that had to work in the salty sea waters. The mechanical shark didn’t work as planned most of the time, creating long breaks during filming and delaying the original production schedule, which was already put at stress for Spielberg’s choice to film in the open sea instead of the much safer and controllable environment of a studio tank with rear projection and miniature effects, a standard technique used on previous seafaring classics like John Huston’s Moby Dick (1956) and John Sturges’ The Old Man And The Sea (1958) and give the movie a proper realistic look. To circle around the issue of the failing mechanical sharks, the director turned to the lesson of master filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock (which he already applied brilliantly in his feature debut, Duel) and rewrote entire sequences, together with Gottlieb, to create a more suspenseful approach based on what is not shown on screen, all orchestrated through ingenious camerawork, blocking and direction of the actors. The outcome is that the audience doesn’t see the shark for most of the duration of the film, but feels its presence constantly thanks to an inspired usage of all the cinematic techniques at Spielberg’s disposal, highlighted by Verna Fields’ clockwork editing. The film’s one big issue turned as one of its truly remarkable strengths, which would definitely be enhanced by the immortal music by John Williams.

The Beginning of a Friendship

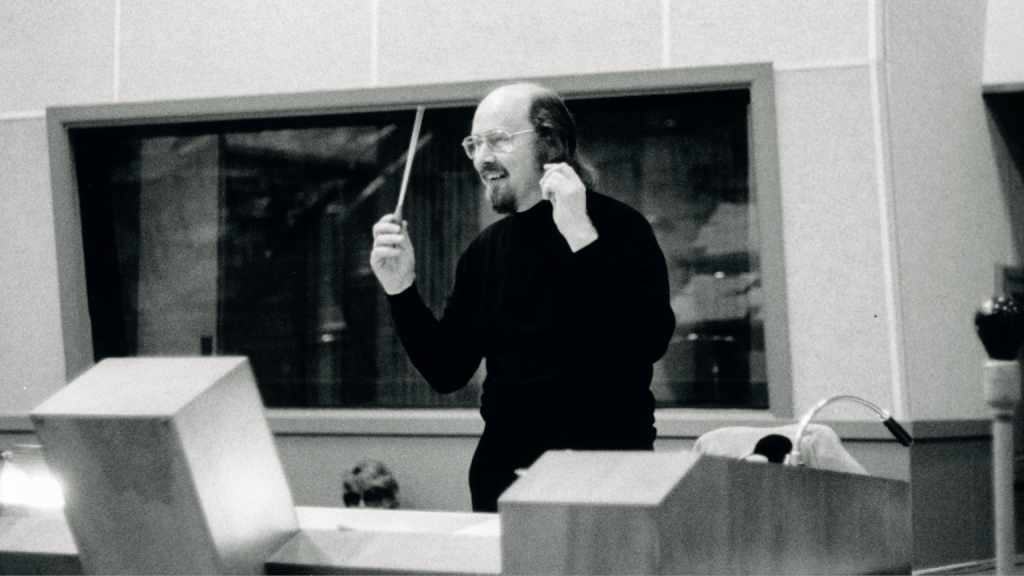

Much has been written over the course of the years on the importance and the substance of John Williams’ score for Jaws—it’s certainly a benchmark in the history of film music, possibly one of the top film scores of all time and one of the true highlights of the entire Spielberg/Williams partnership. The director said many times that the film wouldn’t be as successful as it is without Williams’ masterful score. However, it’s almost educational to look back at how director and composer collaborated to arrive at the end result, which is the perfect synthesis of an artistic relationship based on mutual trust, respect and shared artistic and aesthetic vision. To comprehend even better what this means in the overall scope, it’s important to go back to the first Spielberg/Williams collaboration.

John Williams and Steven Spielberg first met in the fall of 1972, when the director was looking for a composer to score his theatrical debut film The Sugarland Express, which was in pre-production. An avid film music aficionado himself and a lover of the classic film scores of Hollywood’s golden era, Spielberg became aware of John Williams thanks to a soundtrack from a few years earlier: The Reivers, composed by John Williams for the 1969 film by Mark Rydell starring Steve McQueen. As Spielberg recollected in 1983:

“It’s a fantastic score. It took flight… had wings. It was American, a kind of cross between, perhaps, Aaron Copland and Debussy. A very American score!” 2

After a now-legendary meeting in a fancy restaurant in Beverly Hills, Williams accepted to score the film. Spielberg had very clear ideas about the type of score he wanted:

“I called him up and told him I just finished The Sugarland Express and wanted him to take a look. I expected John to write a real symphony. John said ‘You’re going to hurt the movie if you want me to do The Red Pony or Appalachian Spring. It’s a very simple story. The music should be soft. Just a few violins. A small orchestra… maybe a harmonica’”. 3

The young director was at first put off by the composer’s suggestion, as Spielberg admitted later with a smile:

“I’d really wanted eighty instruments. And Stravinsky conducting! Johnny talked me out of that concept and got me to believe the score should be gentle. Almost cradle-like. And so we began a very prosperous collaboration, I think, for both of us.” 4

This type of almost laidback attitude from a then-young director who was already firing on all cylinders in terms of artistic vision and authorship is revealing of the amount of trust he immediately put on his partner composer, enhancing the notion this was already more than a simple creative collaboration. Instead of imposing his own vision to the composer, Spielberg listened to what Williams had to say and accepted his ideas and suggestions. The partnership was a match made in heaven on many levels, but this mutual trust also speaks about the high level of confidence and kinship that would later became exemplary of their successful director/composer relationship. In 2011, Williams summed it up in a very effective way:

“In the forty years we worked together, [Steven] never said once ‘I don’t like that,’ or ‘This won’t work,’ or ‘We need to do something else.’ […] He has enjoyed everything that I’ve done, as I have with him. I may say to him, or he may say to me, ‘Maybe let’s try something else, it might be fun!’ But he has enjoyed everything, even the mistakes. One of the thing that makes the collaboration work is the ability to be unguarded enough to make the mistakes you need to make—not to compete with each other, not try to impress each other, and just to have fun with it. That unbuttoned trust is the essential thing. If it’s there, in the chemistry of the personalities, a lot of fun can be had working together.” 5

A Momentous Occasion

Despite receiving strong critical acclaim and an award for Best Screenplay at the Cannes Film Festival of 1974, The Sugarland Express was a commercial disappointment and seemed to cast dark clouds over the director’s future career: a theatrical debut turning into a bomb can be kryptonite even for the most super of film directors. Spielberg didn’t seem scathed by the less-than-ideal box office figures and immediately dived into his next feature, again courtesy of producing partners Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown: a film adaptation of a soon-to-be-published novel by Peter Benchley titled Jaws, a suspenseful tale about an imaginary beach town community (Amity Island) being put under duress after the unexpected attacks of a giant white shark and the ensuing mission to hunt and kill the predator by three men, namely the town’s police chief Martin Brody, scientist oceanographer Matt Hooper and a rude Ahab-like fisherman named Quint. Spielberg read the book’s galleys while still in prep for Sugarland and courted Zanuck & Brown – who were originally thinking of assigning it to a more mature, experienced director – to let him do it as his sophomore feature film. To the producers’ credit, they stick with the young director even after Sugarland bombed at the box office and gave him ample budget, scale and freedom to create what would have turned into the first blockbuster of the modern era. Trust is again a key word in the process.

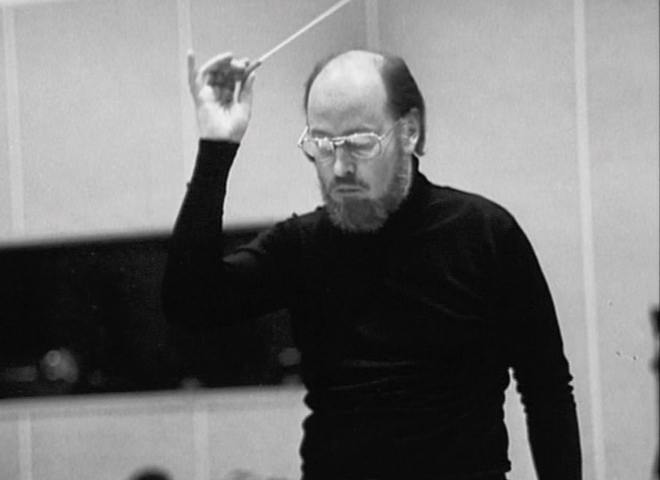

John Williams signed to score the film in October 1974, with Variety announcing the composer’s involvement on November 15. While the previous collaboration was low-key and subdued in terms of scale and approach, Spielberg was sure that Williams would’ve been capable to deliver a score that would harken back to the classic soundtracks he was so enamored with. Spielberg’s instinct was absolutely right and now it’s hard to imagine someone else more perfectly suited than John Towner Williams to fulfill his vision. At that moment in time, Williams was already a highly respected Hollywood professional with 20+ years of experience as pianist, arranger and composer; he already won an Academy Award for his stellar adaptation for the film version of the beloved Broadway musical Fiddler On The Roof; he also composed music for proto-blockbusters of the era like The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno, both of which had hints of the grandiose symphonic exuberance that would become one of his trademarks… Yet, nothing in his resumé was of the same sheer cinematic brilliance of Jaws. As Williams biographer Tim Greiving recently observed, “he was on a launchpad, his engines roaring, and in hindsight it all looks somewhat inevitable. But, I would argue that if he had not been courted by this young, slightly square wunderkind who had very unhip and out-of-date tastes in movie scoring, and had Spielberg not brilliantly made this taut, charming, and operatic sea adventure, John’s career might never have really skyrocketed.” 6

Everything at that point in John Williams’ career seemed to guide him to this assignment, one that would become his real big breakthrough. An event of his personal life also played a factor: the sudden passing of his wife Barbara Ruick in March 1974 left Williams in a state of shock for the better part of the following year—that moment was crucial in how the composer perceived himself as an artist and influenced his own approach to music, as he elaborated very intimately in 2014:

As soundtrack producer Mike Matessino noted in 2015, “It is humbling to consider that the composer’s self-aware artistic epiphany, sparked by personal loss, was so closely followed by Jaws, which solidified his relationship with Spielberg—to say nothing of the fact that Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, The Empire Strikes Back, Raiders of the Lost Ark and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial followed over the next eight years.” 7

When he screened a first assembly of the film, Williams was largely impressed by what he saw and immediately understood its very unique qualities:

“I remember seeing the movie in a projection room here at Universal. I was alone; Steven was in Japan at the time. I came out of the screening so excited. I had been working for nearly 25 years in Hollywood, but had never had an opportunity to do a film like this. I had already adapted ‘Fiddler on the Roof ‘ and I had worked with directors like William Wyler and Robert Altman and others. But Jaws just floored me.” 8

Perhaps because of this series of circumstances, events and inner workings that Williams was able to unlock the film’s potential through one of the simplest yet most powerful musical solutions he ever came up with.

One Shark, Two Notes

In the director’s mind, the role of the musical score was to enhance the eerie, almost supernatural character of the story, but also to accompany the adventurous side. In The Jaws Log, Carl Gottlieb writes:

“John […] was the first person to see the work print outside the studio-executive level. He liked it and immediately got into deep discussions with Steven as they discussed how the music should be approached. They agreed that it was a film of high adventure, and Johnny went to the classic movie scores of the past for a close listen, with Steven playing Stravinsky and Vaughan Williams albums in his office every day, looking for analogies to what he felt should be the themes.” 9

While the film was not cut to music, film editor Verna Fields and Spielberg used a variety of selections as temporary music track to play against the edited scenes and see what approach could work best—among them, the opening piece from John Williams’ score for the 1972 Robert Altman’s film Images was used as temp score for the main titles. The uneasy, uncertain tones of the music would have contrasted the horror of the man-eating beast to make it look like a mythological creature emerging from the depth of the abyss. During a masterclass meeting hosted by the American Film Institute in 2011, Spielberg recounted that the reaction of the composer was one of an alternate point of view:

“When I showed John a cut of Jaws, […] I had temped the movie, I had put temp music into the picture, and I used one of John’s movie scores from his Robert Altman collaboration […] called Images. And because I felt that music was viable, and it was disturbing, and it would make the shark seem like an intellectual (laughs) I was […] trying to make something greater, and more important, that it was ever supposed to be. I was in Hawaii […] when John called me having seen the cut, and John said “Oh, darling boy, no, no, no… It’s a pirate movie! It’s a shark and survivors! Images is not the right sound for this. Let me work something up and I’ll present it to you when I’ve found the music.’” 10

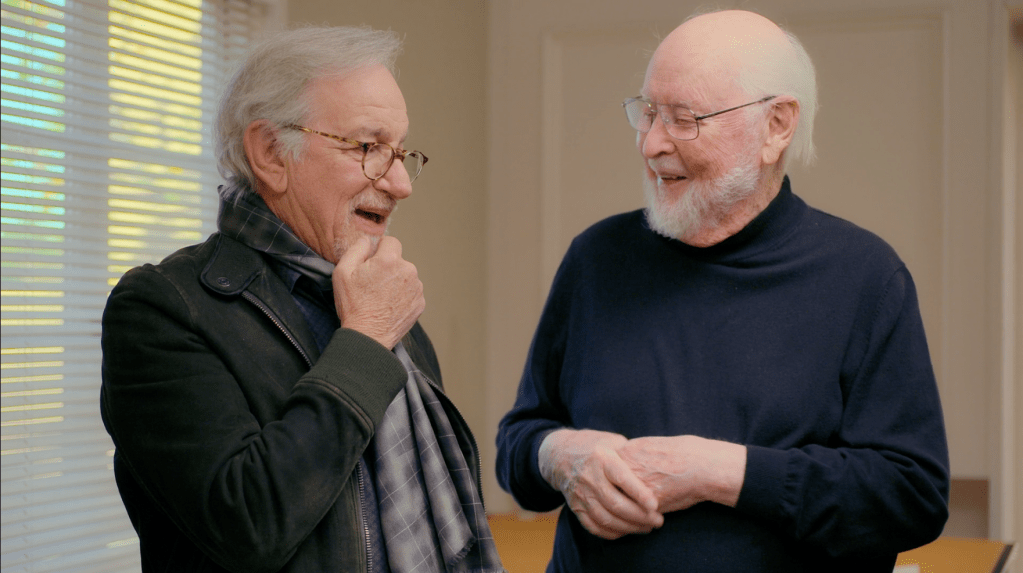

The director listened to his collaborator’s point of view and let him free to make the picture better than it could ever be in his original concept. Spielberg and Williams liked to tell this anecdote over the years (including a lovely moment of the recent Music By John Williams documentary) so we can safely assume these two gentlemen found a real personal connection during the making of this project, therefore the story is not just a nice Hollywood myth being perpetuated, but it’s representative of the level of mutual respect both Spielberg and Williams have for each other, but also of the sheer joy and fun they always put in everything they do together.

It’s also revealing of the composer’s innate sense of drama and his proverbial knack for understanding a film’s true needs in terms of accompanying and enhancing the story and the characters. But it also speaks about Williams’ deep understanding of film language – despite him often saying he’s never been a lover of cinema – and how music can create new levels of meaning otherwise absent on the screen. It’s not just musical storytelling, it’s musical dramaturgy.

When Williams presented Spielberg the main theme for the picture, the director was initially flabbergasted, but soon was convinced it was the right approach for the film. Williams’ simple idea unlocked the film’s full potential of drama, suspense, adventure and excitement. The Shark Motif is a figuration based on a semitone of E and F, usually presented in the low end register of the orchestra (basses, celli, low woodwinds, trombones and tuba), built on an insistent rhythm (in musical terms, an ostinato) that Williams carefully slows or accelerates always in support of the film’s dramatic needs. In 2015, he told journalist Jon Burlingame:

[It’s] so simple, insistent and driving, that it seems unstoppable, like the attack of the shark. […] I just began playing around with simple motifs that could be distributed in the orchestra, and settled on what I thought was the most powerful thing, which is to say the simplest. Like most ideas, they’re often the most compelling.” 11

Williams also remarked that the theme “is grinding away at you, just as a shark would do, instinctual, relentless, unstoppable”. The description is all the more evident in the opening credits of the film, where the menace is born out of the bowels of the Earth in the deep ocean and slowly, but steadily (“gradually becoming insistent,” indicates Williams on the score) approaches his next victim.

The musical idea represents the uncompromising, primal character of the beast. Williams’ modus operandi is perfectly exemplified in the opening scene, where the music enters quietly and almost creepily, with chromatic piano and harp arpeggios punctuated by the low end of celli and basses. The music slowly builds in tension and also in size, and finally launches a violent, Stravinsky-ian orchestral attack. The music becomes relentless as the shark attacking the poor victim before slipping away almost as silently as it appeared.

Every subsequent shark attack scene in the first half of the film follows the same pattern, and Williams carefully and cleverly spots the musical cues to alert the audience when it’s time to get worried, frightened, or relieved—in every occasion, the music literally becomes the character.

The orchestration of the theme is peculiar because, besides the low basses, celli, low woodwinds and trombones playing the ostinato, features also a highly chromatic ascending motif played by tuba, which became a staple for every tuba player in the world ever since. The motif is heard not just in the main title, but occurs many times throughout the picture and requires a particularly athletic playing as it’s written in an uncharacteristic high register for the instrument. On the original film score recording, the solo is performed by Los Angeles studio musician Tommy Johnson, a legend among his peers and principal tuba in countless film scores, including many by John Williams until the late 1980s. This motif is used by Williams to underline the evil nature of the shark, or its essence as a mind-numbing voracious creature (it makes its entrance as the title card “JAWS” appears on screen), so it could be interpreted as a sort of “bad guy” theme. It’s an essential ingredient to the overall effectiveness of the shark’s theme, playing in perfect conjunction with the throbbing two-note ostinato.

Much More Than Two Notes

The genius of John Williams’ invention for the shark is lauded and recognized by virtually everyone, but the score is much more than its main theme. The whole film is a masterclass in film scoring for its judicious spotting, the effectiveness of the material, the ability of enhancing emotions beneath the surface and finally for the composer’s skill in creating self-contained satisfying musical episodes. During the first half of the film, Williams’ music enters only when it’s strictly necessary and let the tension surge also by staying out of the way, highlighting not just the dread and the fear caused by the shark, but also the ensuing drama of the characters. The touching scene when a dejected Chief Brody (Roy Scheider) is reflecting silently at the dinner table and his little son starts to mimic his gestures is accompanied by Williams with a sweet musical vignette for piano, celesta and harp, on a low bass pedal that still reminds us of the danger underneath; when Brody and Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) go for a night search of Ben Gardner’s boat, the score becomes eerily evocative, with a misterioso piece featuring solo flute and a delicate web of strings and woodwind trills; as tourists flock to Amity on July 4th for the summer’s opening despite the shark alerts, they march on accompanied by Williams’ playful pseudo-baroque promenade featuring solo trumpet and harpsichord, an almost parodistic commentary for the ensuing insanity. These episodes give the score variety and help expand the scope of the film itself beyond the shark motif during the first act of the film. But it’s when the hunt is about to begin that Williams starts firing on all cylinders.

Heading Out To Sea

To contrast the primal character of the shark, Williams depicts the adventure of Brody, Hooper and Quint (Robert Shaw) going on the hunt of the shark with various musical subjects of highly complex nature. When the Orca sails away from Amity Island’s haven, the three men are accompanied by a jaunty hornpipe-like melody. Taking a cue from the character of fisherman Quint, who often sings on camera an old English ‘sea shanty’ called “Spanish Ladies,” Williams crafts his own spirited sea tune, scored for full orchestra and developing with intricate contrapuntal writing. The extended version of the piece as recorded for the original soundtrack album features a playful trio for horn, trumpet and piccolo playing in counterpoint sophisticated yet airy lines, possibly a fun musical reference to the three men on the boat and their constant banter with each other.

Once the hunt is on, this musical subject turns both heroic and exciting as it accompanies some of the film’s most gripping and exhilarating sequences. Williams deploys true symphonic mastery, intertwining the various musical motifs and working in perfect synergy with the film’s mounting excitement in conjunction with Verna Fields’ top-notch editing. The shark ostinato surges to epic proportions, with Williams adding a soaring minor mode motif for the high-angle shot where we finally see the size of the animal (“That’s a 10-footer!” says Hooper, “25…” replies Quint). The action becomes more urgent and the music gets more frenetic and exciting as the three men try to harpoon the shark. The Korngold-esque fanfare heard during the climax of the chase is probably the utmost example of Williams’ “pirate movie” approach for the film.

“It suddenly becomes very Korngoldian, you expect to see Errol Flynn at the helm of this thing. It gave us a laugh.” 12

Williams enhances the heroism of the scene (originally titled “Man Against Beast” on the film’s score manuscript) with uplifting music, helping the sequence to become an irresistible piece of filmmaking craft at its finest, in which the director and composer found a perfect synergy. One could be almost tempted to state that this scene was the exact birthing moment of the Spielberg/Williams magic that would have carried on for the following years and decades.

The sequence also defines one of Williams’ most brilliant and unique skills as a composer of film music: the apparently effortless capability of writing a piece (or “cue,” as it’s called in the film scoring vernacular) that closely accompanies and enhances the various beats of the scene, hitting numerous of sync points and visual cues, but never resorting to mere mickey-mousing technique: quite the opposite, Williams structures the piece with a natural, organic flow that can be appreciated also as pure music. The composer elaborated on the challenges and the intricacies of composing a piece of music following all these visual synchronization marks during an interview with conductor Stéphane Denève in 2016:

An Eerie Interlude

If the second half of Jaws is brimming with a sense of seafaring adventure, Spielberg is careful to remind the audience what’s at stake for the characters. In addition to adding much needed comedic beats in the interplay between the three men that help both releasing the tension and creating a relatable connection with them, the director brings a defining character’s moment on screen with the eerie shark tale that Quint offers to his fellow boat comrades during a quiet moment of the lone single night the three men spend on the Orca. Known as “the Indianapolis speech,” the 4-minute monologue (whose uncertain origin has been endlessly debated among Jaws fans) is a bravura piece of filmmaking that involves Robert Shaw’s chilling performance, Bill Butler’s lean but very effective lighting, Verna Fields’ subtle editing (five different camera set-ups that feels like one continuous shot) and finally John Williams’ insidious musical accompaniment. The composer is often lauded for the mastery in scoring grand action scenes and big setpiece-like moments (including several in Jaws), but his skill in serving dialogue and character-driven moments is equally top-notch as this sequence demonstrates. Williams’ music doesn’t enter until one minute into Quint’s monologue (“Very first light, Chief, sharks come cruising…”) when the tale starts to become frightful: over a bed of high-pitched strings, a lone harp plays a downward chromatic scale, accented by quiet gong hits and low woodwind figurations. As the tale gets more chilling, the woodwind texture becomes thicker with alto flute, oboe and clarinets, and muted horns playing the “evil shark” motif. Williams’ textural scoring supports the dialogue with subtle and effective touches, augmenting the sense of dread and fear of the audience and cleverly foreshadowing the character’s fate at the same time.

A Fugue, The Final Confrontation and Quiet After the Storm

As the hunt becomes more dramatic and the stakes are raised, Williams heightens the tension with a beautiful fugato-like composition to accompany the building of the shark cage and the subsequent final showdown. Fugue is probably the most complex musical form ever invented and Williams uses it to highlight the intellectual side of the three men in their fight against a pure force of nature. If the shark is carrier of the most basic and primal musical idea, the trio of Brody, Hooper and Quint becomes the vessel of one of the most ingenious invention of the musical mind. As Jon Burlingame noted, “Williams composed a Bach-like piece that both indicated the complexity of the job and the urgency of the moment.” 13

The piece became one of Williams’ own favourite selections from the score and was furtherly expanded in a fantastic concert version that also includes the “Out to Sea” extended arrangement, followed by the shark cage fugue episode. In this presentation, Williams creates a fully fledged symphonic piece with a great feeling of “prelude and fugue” in its most classical sense. The composer performed the piece many times in concert over the years: it has become a staple of his concert programs and has been performed also by the prestigious Vienna Philharmonic and Berlin Philharmonic. It’s indeed a piece that orchestras are clearly very engaged and satisfied to perform live, as it requires the highest level of musicianship. Williams also recorded it himself with the Boston Pops Orchestra in 1990 for the first volume of his classic Spielberg/Williams Collaboration series.

Jaws reaches its climax with the victory of the man’s spirit against the brutality of nature, but before that the heroes have to go through their most desperate hour. Hooper goes into the cage and plunges into the depth of the sea planning to poison the shark with a harpoon, but the rage of the beast is such that it devastates the cage and forces Hooper to find shelter from the voracious monster: the heart-stopping scene (which contains some of the film’s terrific underwater photography by Ron and Valerie Taylor featuring a real shark) is accompanied by Williams with a ferocious piece full of dizzying strings and vortex-like harp glissandos.

The shark then comes back on the surface, where Quint meets his fate in its jaws. Williams originally wrote a brutal variation of the shark ostinato which grows to a violent apex, but the cue was wisely dialed out in the final mix: the grisly scene is much more chilling without any musical accompaniment. Again, an apt demonstration of Spielberg and Williams understanding that, in the economy of the film, less is more. The piece in itself is terrific though and makes for a compelling listen away from the film.

Brody is now alone to face the monster on a sinking Orca and must think and act fast in order to save his life and turn the tide at the very last moment. Spielberg stages the final confrontation between man and beast as an epic Melville-like setpiece, with Williams’ music carrying the weight of the scene with an exciting action piece that addresses both the nail-biting tension and the heroism. Brody fulfills the Hero’s Journey by literally slaying the dragon: the shark blows up with a timpani roll and the victory is celebrated with a noble figuration for french horns, followed by peaceful chromatic piano arpeggios to comment on the animal’s demise.

Hooper comes back to the surface and reunites with Brody: after sharing a liberating laugh, the two survivors swim back towards the coast using the remains of the Orca as a vessel, accompanied by the calming sounds of seagulls and a serene, peaceful rendition of the hornpipe theme scored for strings, flute and trumpet. It’s the perfect curtain closer, acting as the quiet after the storm, leaving the audience with a sense of liberation and fulfillment after experiencing two hours of thrills and chills.

A Mythical Tale With Timeless Music

Today is almost too easy to realize how much of the primal nature of the film, i.e. to scare the hell out of the audience, achieves its goal in large part because of John Williams’ classic score, but while it is certainly music that the audience notices during the film, a lot of its effectiveness goes under the skin and acts in subtle, almost subliminal ways, interacting with both our psyche and our emotions. Even more than that, the music helps the film to reach its status of mythological tale. On the surface it may look like a story about a killer shark or even just a well-made monster flick, but Jaws becomes something much more profound and meaningful when we plunge into the depth of its waters: It depicts the eternal struggle of Man vs. Nature and its almost theological implications, much like Herman Melville’s Moby Dick; it celebrates the courage of men, but also comments on the weaknesses and frailties of human beings during a time of crisis that put a community on the brink of collapse, especially when obtuse male characters are in positions of power; it talks much better and more directly than many sociological analysis about who we are as a modern collective society. Through their most impeccable craft, the filmmakers take us on a journey and make us feel compelled from the first frame to the last. The shark’s POV shot that opens the film, those two throbbing notes, and all that follows for the next two hours are part of the collective memory of at least two generations of people, and one of the most rightfully lauded achievements in the history of films and, for better or worse, the benchmark for virtually all the summer blockbusters that followed.

That is achieved in no small part thanks to John Williams’ masterful score. As Steven Spielberg wrote in the liner notes of the Jaws original soundtrack album, “The music fulfilled a vision we all shared.” 14 John Williams’ score reached something more than just a cult status among movie fans: it transcended its film origin to become synonym of dread, danger and terror. In addition to becoming a venerated object of pop culture endlessly referenced, quoted and spoofed, Williams’ music for Jaws relates to the more primal side of our feelings (what’s more primitive than fear?), but also reminds us about the heroic nature of the human spirit. In recent years, John Williams often spoke about the ancient roots of music and how much of its presence in our lives goes way back to prehistory.

I really believe that music is older than language—probably when we were in our Paleolithic time, we wouldn’t speak yet, but we would beat a drum or we would blow on a reed or something as a warning, or to excite an animal, or to discover one in some way—musical expressions that would belong to our humanity. 15

Consciously or just instinctually, John Williams struck a chord that goes back to our ancestors and found a way to make the audience (re-)experience those primal feelings, creating a timeless music that sounds both familiar and fresh, be it when it winks nostalgically to the classic film scores of Hollywood heydays or when it goes to a mythical past we all shared, similarly to what Igor Stravinsky achieved with his seminal ballet score Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring). Jaws is all that, and if it wouldn’t still be enough, then it should be lauded for cementing the artistic partnership between Steven Spielberg and John Williams, who became the epitome of the director/composer relationship like very few others in the history of film. The composer won his second Academy Award (the first for an original score) and rose to become one of Hollywood’s major film composers.

The newly remastered 50th Anniversary edition of the original film score recording – now available on vinyl from Mondo Records and digitally on all streaming platforms, with a Special Edition CD release coming soon from Intrada – finally give the chance to enjoy John Williams’ stunning achievement as a separate listening experience thanks to the thorough restoration handled by producer Mike Matessino, which finally gives the music an unprecedented vibrancy in terms of sound fidelity, dynamic and presence. But that’s not the only version of this music that is being released…

Play It Again, John…

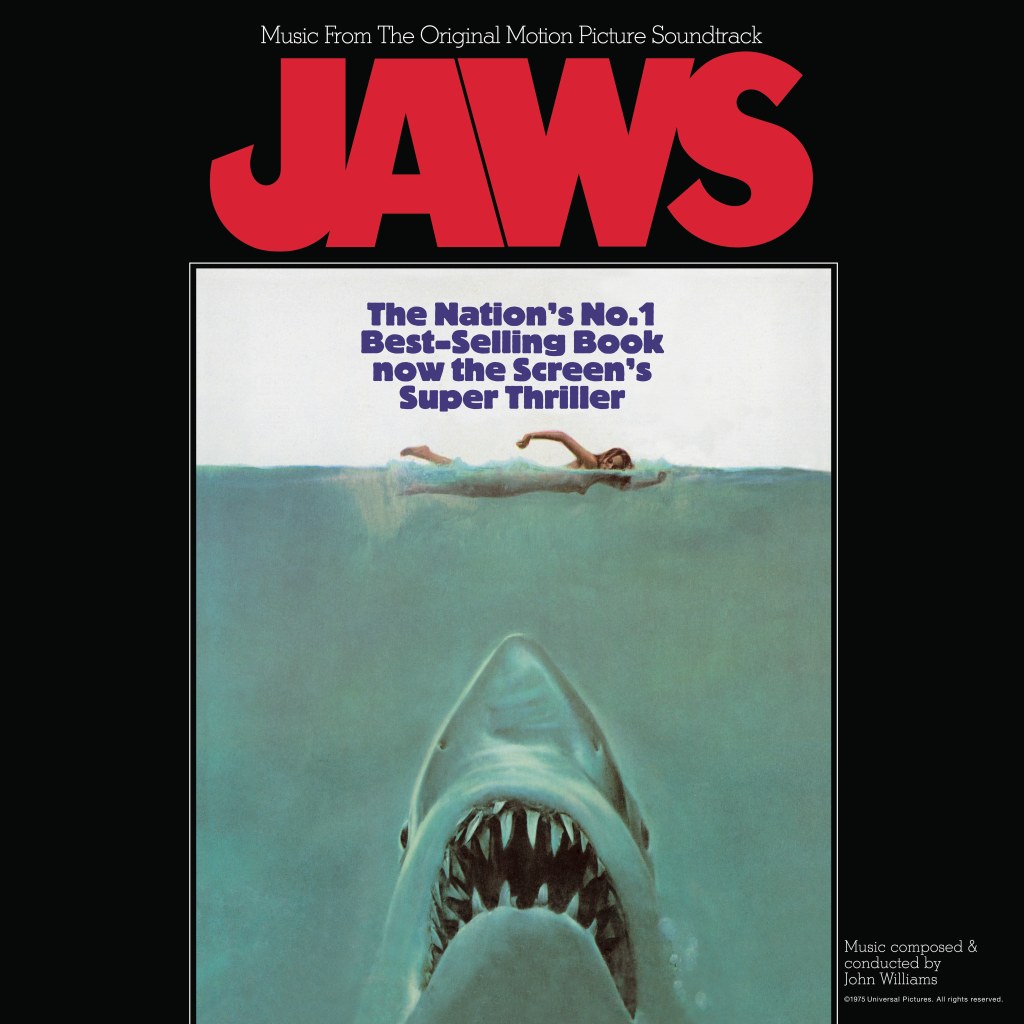

The creative achievement and the effectiveness of John Williams’ score for Jaws was immediately evident right after it was recorded on March 3 and 4, 1975 (with an additional date held on March 10th for source music) and used in some of the film’s early test screenings with an audience. The buzz on the score was so strong that it possibly induced the composer to think about a special treatment of his music for the soundtrack album planned by MCA Records (the then-recording arm of Universal Studios) in conjunction with the film’s theatrical distribution. Instead of creating an album program using the cues as recorded for the film, Williams took the bulk of the written material, selected several highlights and refashioned them into fuller, more developed pieces in true symphonic fashion for a more compelling listening presentation. Then, on April 17 and 18, 1975, he gathered the same pool of musicians contracted by Sandy DeCrescent who performed on the film score – which included trumpeter Malcolm McNab, french horn player Vince De Rosa, flutists Sheridon Stokes and Louise Di Tullio, pianist Ralph Grierson and tuba player Tommy Johnson – and re-recorded the music at Warner Bros. Scoring Stage (then known as The Burbank Studios). It’s a fascinating alternate reading of the same music, possibly performed with even more panache and gusto than the already impressive film score recording, as in this case the performance was not subjugated to the needs of millimetric synchronization with the film, but instead was interpreted as “pure” music. In addition to the more fine-tuned performance, Williams slightly re-orchestrated some of the material and wrote ingenious and tasteful extensions that gave some of the pieces a much more developed and musically engaging structure: the shark theme ostinato is presented in a formal setting (“Theme From Jaws“) that became the basis of the famous concert version still performed today; the tourist montage is arranged and extended as a jaunty neoclassical menuet (with the hilarious subtitle “Tourists On The Menu”); the uplifting barrel chase sequence is extended with a rousing, exhilarating symphonic coda; and the already mentioned “Out To Sea” and “Preparing The Cage” (a.k.a. “The Shark Cage Fugue”) are probably two of the stand-outs arrangements considered the jewels in the crown of this score. It’s a fun and terrific listen, shaped by Williams as a sort of nautical symphonic poem in which memories of the film are reminisced, but also offering a satisfying self-contained musical narrative that is able to evoke more personal images in each listener. The album (labeled “Music From The Original Motion Picture Soundtrack”) was a phenomenal success and reached the Billboard charts as one of the best-selling soundtracks of the year, foreshadowing what would happen a couple years later with Star Wars. The back cover of the LP also included a Spielberg-penned note gushing over the artistry of his composer’s friend, the first of many that would appear on the soundtrack albums of his films. The album went on winning the Grammy Award in the Best Original Score Written For A Motion Picture Or A Television Special category, the first of the 26 Grammys that Williams would end up collecting since then. For the new 50th anniversary reissue, the album recording has been painstakinlgy remixed and remastered by producer Mike Matessino from newly found multi-track session masters, restoring the brilliance of the original performance with astounding clarity.

In addition to celebrating the 50th anniversary of the film and its music, these new remastered editions of the Oscar-winning original film score and the Grammy-winning soundtrack album recording offer a chance to furtherly appreciate the brilliance of John Williams’ genius and reflect on the score’s status as one of the major achievements in the history of film music.

Special Thanks to Mike Matessino, Tim Burden, Tim Greiving and Jim Ware

Visit Jaws50music.com to learn more about the 50th Anniversary Soundtrack Releases

Footnotes

- The Making of Jaws, documentary by Laurent Bouzereau, Universal Home Video, 1995 ↩︎

- Tony Crawley, The Steven Spielberg Story, Zomba Books, 1983 ↩︎

- id. ↩︎

- id. ↩︎

- Steven Spielberg and John Williams: AFI Masterclass, Turner Classic Movies, 2011 ↩︎

- Tim Greiving, “Jaws at 50: the Big Bang of John Williams,” Behind The Moon, 2025 ↩︎

- Mike Matessino, “The Theme Is Still Working,” Jaws – Music from the Motion Picture liner notes, Mondo, 2015 ↩︎

- Jon Burlingame, John Williams Recalls “Jaws,” Film Music Society, 2015 ↩︎

- Carl Gottlieb, The Jaws Log, Harper Collins, 1975 ↩︎

- Steven Spielberg and John Williams: AFI Masterclass, Turner Classic Movies, 2011 ↩︎

- Burlingame, John Williams Recalls “Jaws,” Film Music Society, 2015 ↩︎

- id. ↩︎

- id. ↩︎

- Jaws – Music from the original motion picture soundtrack, MCA Records MCA-2087, 1975 ↩︎

- “John Williams In Conversation with Deborah Borda,” The Kennedy Center YouTube channel, 2022 ↩︎