On Saturday night, we witnessed a miracle in Massachusetts.

John Williams, 93 years old and facing considerable health setbacks since last April, came to Tanglewood and presided over the premiere of a new, 20-minute concerto for piano and orchestra.

The fact that he is still with us, in 2025, is a miracle.

The fact that he made the long trek, having rarely left his home for the past year, is a miracle.

And the fact that he has composed a robust, challenging new concert work at this juncture is an astounding miracle.

We who have loved his music since our childhood—some as far back as the 1960s—are still sharing planet Earth with John Williams, still seeing him on his beloved Tanglewood grounds, still hearing new music from his formidable mind. It’s honestly hard to comprehend.

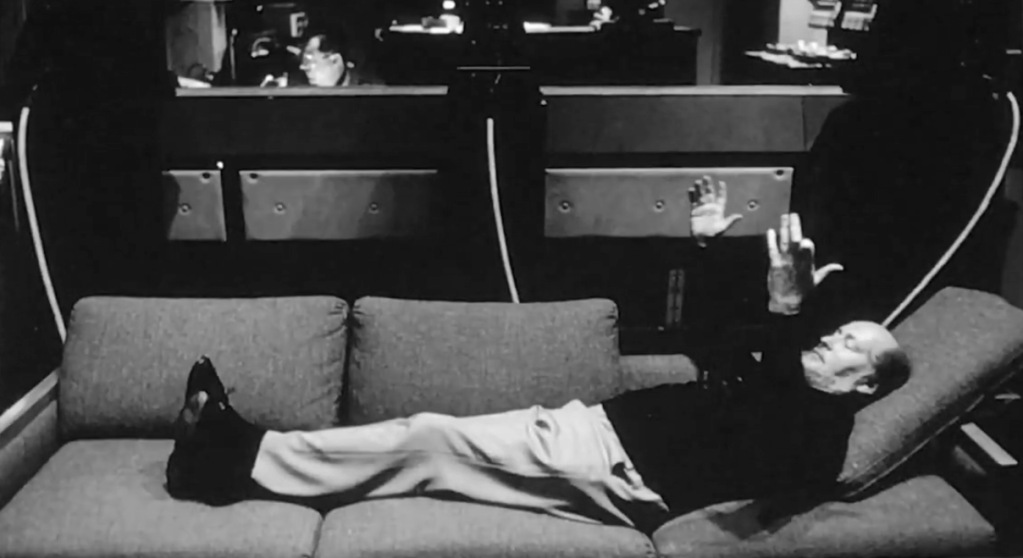

John made the journey earlier in the week, along with his daughter Jenny and his usual entourage. He attended three rehearsals in the Koussevitzky Music Shed (the main performance venue on campus), sitting right by the stage near the piano, following along the printed score on a music stand. He was concentrated and deeply engaged, occasionally giving Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor Andris Nelsons a slight tweak in performance direction, or explaining how the tempo can be more dancelike, or paying his compliments to a soloed musician. At times, he would sing what he meant. It was so beautiful to see him back in action, back with his cherished orchestra (this summer marks the 45th anniversary of John being appointed music director of the Boston Pops)—and clearly energized and enthused about delivering his new “baby” into the world.

He wrote the piano concerto specifically for Emanuel Ax, an old acquaintance and a seasoned virtuoso, and to some extent he wrote it to show off “Manny’s” considerable chops. (I wrote about the origins of the piece for the New York Times last week.) Like most of John’s classical works, the concerto is abstract and nonlinear, and it tests the muscles and dexterity of the soloist nearly to their limits. This concerto is full of cadenzas and “quasi improv” solo passages (all completely notated), so Ax often had a spotlight on him as he walked a tightrope across the keyboard with no net.

There was an amusing moment when I visited John at his studio in November 2023, in the midst of writing my biography. He said he was working on the first movement. “It starts with a cadenza,” he said, getting up from his chair and moving to the piano, then halting. “Which I won’t play for you… because I can’t.”

These passages are not only challenging to the performer—they are also the most challenging for the average listener, especially the average fan of John’s film music. Where his film writing is often a kind of endless melody, etching into the ear like a great pop tune or aria—memorable, emotional, and lyrical—his classical cadenzas are often fractal and random-sounding, decidedly not designed for Top 40 radio or the faint of heart. In the piano concerto, particularly the first movement, the solos sound chaotic and almost angry—sometimes banging, sometimes leaping, sometimes trilling—like a wanderer without a home.

And it’s not even “random” in a jazzy way. Despite John’s invocation of three jazz piano legends on the score for each movement—Art Tatum, Bill Evans, and Oscar Peterson—this is not a “jazz concerto” in any way. “I wouldn’t want that,” he said when I asked him about this. “First of all, I don’t think I could do it, effectively. As far as I know, there isn’t one, which is a very interesting thing to think about.”

I reminded him of Phil Moore’s piano concerto, premiered in 1947—which, when you read my book, you’ll understand the significance of that piece in John’s early career. John also mentioned a concerto he recently heard by Yehudi Wyner, which he thought “sounded American, in a way that it would have succeeded at some kind of jazz sensibility level. But apart from that, I don’t know any. It’s not something I want to try to do.”

So, John’s seance with jazz pianists here is strictly spiritual (“it only addresses their sound,” he explained), and not at all a return to his jazz piano days. Which, for some of us, is probably a little disappointing. We know he could write a true jazz piano concerto, and it would be amazing. But, for whatever reason, he’s just not interested in that. Nor is he interested in writing a concerto in the familiar, instantly approachable style of his film scores. In John’s mind, there is essentially a chasm between the two worlds. Film music should necessarily be economical, direct, often reminiscent of a time and place, often tuneful. “Knowing, as we do, that the audience can’t listen,” he says. “Their attention is too distracted from noise or dialogue, and so on. Triple fugues and film scores… I don’t think so,” he laughed. Whereas pure music ought to be much more elaborate and complicated, or at least unbound to the inherent restrictions of accompanying a motion picture.

When it comes to a showy, technically demanding concerto for a soloist like this, the piece almost seems designed to be seen as much as heard. It’s a feat, a display of incredible skill. Thankfully we had very good seats for this on Saturday night—a direct eye line to Ax’s hands and his deeply focused facial expressions. This helped me appreciate the “thorny” (in Ax’s words) nature of his starring role in the piece, despite the fact that, I’ll admit, I struggle with cadenzas and solo writing that isn’t trying to entertain or sooth or seduce.

But when the orchestra joins in, there is a warmth, a sympathy, a grounding to the piano’s seeming lawlessness. John’s orchestration in this piece at times reminded me of A.I. (my all-time favorite score), Nixon, and even Born on the Fourth of July.

The second (slow) movement is impressionistic and more obviously tonal. It begins with a fragile duet between solo viola and piano (when asked about this, John said, “I just simply wanted to hear them play”); then the other strings waft in like a refreshing breeze. This movement is dreamy and slightly melancholy—John described Bill Evans’ playing style as “velvety in the balance”—and easily the highlight of the whole concerto.

Well, except that the third movement, John’s ode to Peterson, is really, really fun. It opens and closes with war-pounding timpani, and takes John’s idea of Peterson’s “circus” sound and runs with it. This is one of John’s classical action cues: athletic string ostinatos, marimba and glockenspiel runs, and some drooping muted trombone slides for a funny seasoning. The last two minutes wind the piano and orchestra up and race them both toward an explosive fireworks finale, as crowd-pleasing as any of John’s classical works have ever been.

There is a conversational theme to the various namings of this piece (“Colloquy,” “Listening”)—and the concerto is in conversation with many other John Williams compositions. Starting, most obviously, with his solo piano fantasia for Gloria Cheng… called Conversations.

There is a lot of shared DNA between these two works—in the challenging, modernist solo piano writing, but also in the explicit references to Evans and Phineas Newborn, Jr. John relayed to me how an English vibraphone player named Victor Feldman taught him the complicated Newborn passage when they were sitting next to each other in Henry Mancini’s Peter Gunn orchestra, and he wove this old relic from his jazz piano days into both Conversations and the piano concerto. “Same passage, not developed,” he said—“not anything, just played as a commentary.”

Then there is also the fact that he wrote featured solos for both Cathy Basrak—who John composed his viola concerto for in 2009—and her husband, timpanist Timothy Genis. (A movement in the viola concerto, which has them dueling each other, he cutely called “Family Argument.”) He also gave a prominent role to celeste, positioned directly behind Ax’s piano on stage, which has been a staple of John’s music since as far back as his flute concerto, but more famously in his scores for the Harry Potter films, as well as The Fabelmans.

With this concerto, it’s as if he called on several of his old “friends” in the orchestra: there is the spotlighted timpani, which is what his dad and both of his brothers played; and the trombone, which was John’s very first instrument and the one he had the most passion for before his dad persuaded him to focus on the piano. John said he tried to write a percussion concerto some years back, but only “got about as far as the timpani” before giving up. “I may get around to it,” he said.

He also once contemplated writing a trombone concerto. “I think I can say: what there is to know about the trombone, I know,” he said. He’s been asked to write one repeatedly by New York Philharmonic trombonist Joseph Alessi. When he heard Christopher Rouse’s concerto for Alessi in 1992, he thought it was the “greatest thing I’ve ever heard, the greatest trombone playing I’ve heard. I told that to Joe, and he said, ‘Well, write me something!’” John explained that his concerto would have had a similar concept to the piano, basing each movement on trombone icons from the past—Jack Teagarden, Frank Rosolino—but, for now at least, it remains only an idea.

Naturally, the piano is John’s dearest friend, and this piece was a conversation with not just the ghosts of the named jazz greats, but also with the ghosts of all of John’s old piano teachers—from Bobby Van Eps to Rosina Lhévinne. So, the piano concerto is a deeply meaningful piece in his oeuvre, composed at a late hour in a legendary life—and there is a lot going on between the notes.

And its existence is a miracle.