Hosted and Produced by Maurizio Caschetto

LISTEN:

There are several crucial figures in the creation of a film score whose work remain more or less unknown to the general audience and far removed from the spotlight, but without whom it would be impossible to have music properly recorded and delivered. Orchestrators, copyists, librarians and proofreaders ensure that the final result is exactly in line to what the composer originally envisioned and that the music will sound perfect the day of the recording. It’s a small armada that helps the composer keeping the score up to date to the most recent cut of the film and help them to navigate through the whole process of producing a film score. The methodology varies depending on each composer’s own preferred workflow but it can be roughly summed up as this: the composer writes the cues as sketches, either a handwritten short score or a synthesizer demo a.k.a. mock-up; the sketches then are handed to an orchestrator or an arranger (usually a trusted collaborator of the composer), who expands them into a full orchestral score, adding embellishments if necessary—this practice varies extremely from composer to composer and has been subject of discussion and much speculation over the years—and completing the orchestral vest. The music preparation team then takes the the full score and extracts all the individual parts from which musicians will read during the recording session. This fundamental aspect of the job is overseen by the head of music preparation, who proofreads the score and makes the final necessary adjustments and corrections if needed—film music is often written at a very hectic pace, so it’s crucial to double- and triple-check every passage in order to have music that reads very clearly and that is instantly playable by the orchestra. The full score and parts are finally handed to the librarian, who will collect and put them on the music stands of the orchestra and the conductor’s podium the day of the recording in the running order that has been established by the composer, making sure that each part is up to date and without errors. Back in the old days, all of this process was done by hand, with a team of amanuensis creating every single page with ink on paper. Studios used to have their own staff of people doing the job of music preparation, but after they dismantled their music departments, all the work was outsourced to external vendors. When music notation programs and MIDI softwares became a standard of the industry in the 1990s, the job turned gradually to the current digital practices, with the music prep team extracting individual lines directly from synth mock-ups and loading them into notation softwares to create the final score parts.

The head of music preparation is one of the most important member of the team that creates a film soundtrack and, together with the music editor, is often the composer’s right-hand person. In a business-driven world like film the clock ticks away inesorably and time equals money, so it’s essential to have people who are savvy and quick to avoid situations where there may be unexpected delays that could quickly turn from a momentary halt into a hemorrage of money. It’s a person who also has to speak the language of music clearly in order to ensure composers that anything can be changed on the spot during the recording sessions.

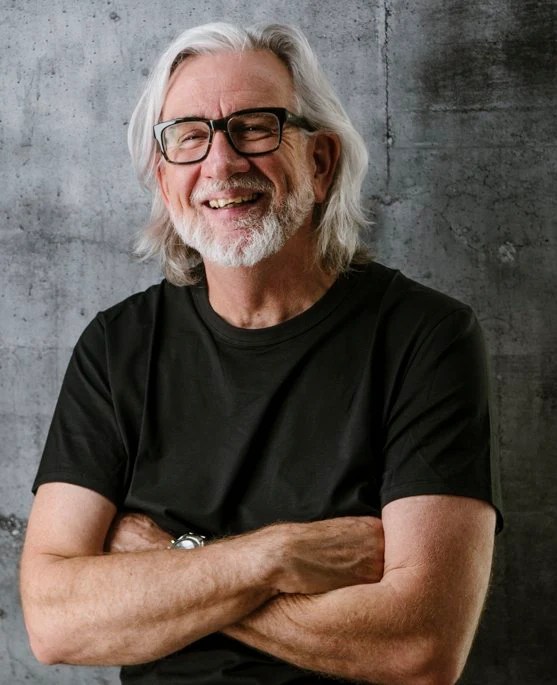

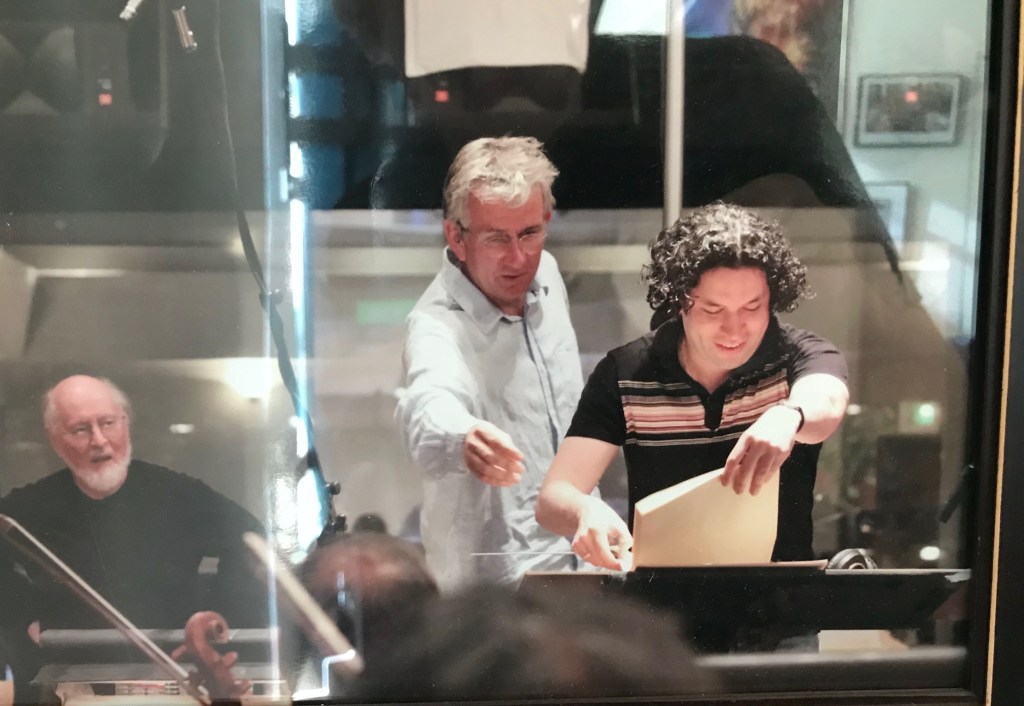

Mark Graham is Hollywood’s first-call “music prep man” and a name trusted by the entire community when it comes to the preparation and the recording of film scores, having worked as orchestrator, conductor, head of music preparation, librarian and copyist on literally thousands of film and television projects. Born and raised in England, Graham began his professional career as a trombone player before moving to arranging and music copying jobs, working in the field of commercial music and also for the theater. He moved to the United States in the 1990s and began working as copyist and score preparator soon after. He started to collaborate with John Williams in the late 1990s as part of the music prep team, taking the mantle from Williams’ longtime trusted music preparator and librarian JoAnn Kane, who founded JoAnn Kane Music Service in the mid-1980s, the leading music preparation company for virtually the whole industry.

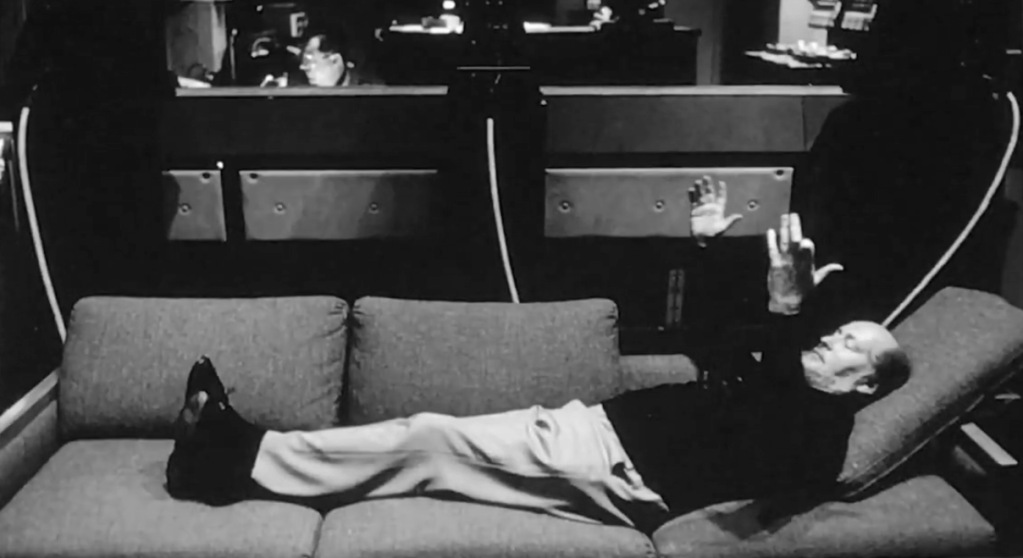

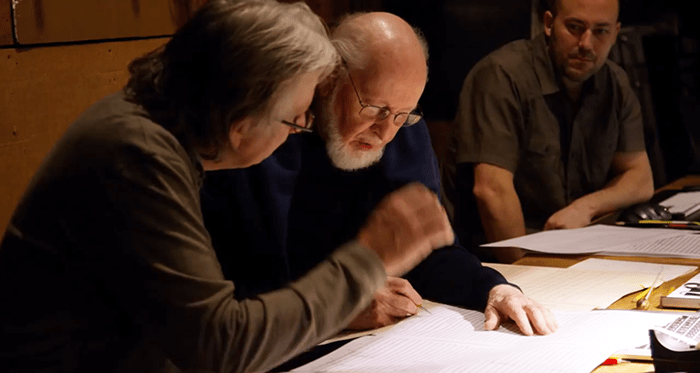

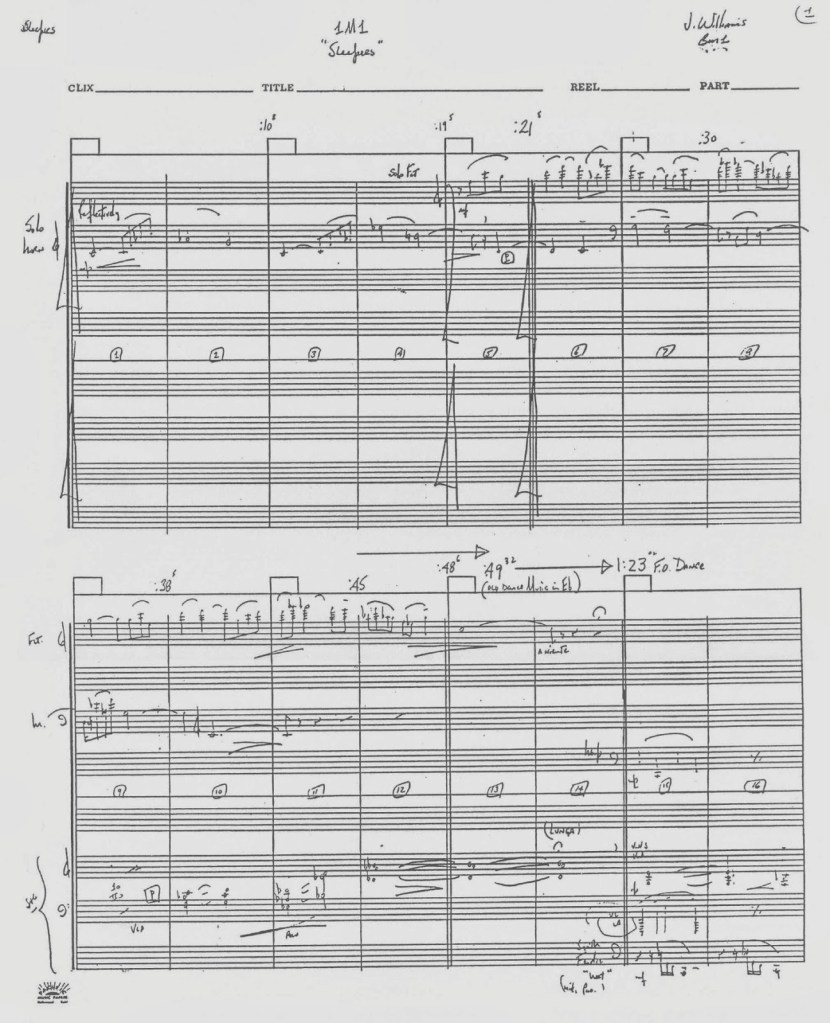

Graham inherited JoAnn Kane Music Service and became the owner of the company, becoming Williams’ right-hand man for music preparation of all of his works. During all these years, Mark collaborated very closely with Williams in a key position, seeing first hand his working method and becoming a trusted colleague who ensured that everything would always go smoothly and efficiently. Williams is one of the very few composers who never changed his modus operandi and still works with the tools he always used: with a cue sheet prepared by the music editor breaking down the timing of the scene, he sits at the piano and writes the cue with pencil on an 8-stave sketch paper, using a stopwatch to check the timings and calculate the sync points. Differently than many other colleagues, Williams didn’t turn to digital practices (“I kept working a lot, so I never had the time to go back and retool myself,” he often said), so it has always been crucial for him to have people he can trusts completely when it comes to hand over his handwritten sketches (actually a short, or “compressed” score in which all the dynamics, tempo markings and orchestral colours are already notated down to the smallest detail) and prepare the parts for the day of the recording.

The level of accuracy and detail of Williams’ sketches means he doesn’t need a large team to create the final product: On the contrary, his process requires just a few people who can ensure a fluid and efficient workflow that guarantees he always gets what he wants. For many years, Williams used to turn his sketches to a trusted colleague orchestrator whose task was to proofread them and prepare the full score manuscript: Herbert Spencer was his main orchestrator from the late 1960s to 1990; Alexander Courage and Al Woodbury would also help out on some of the bigger projects, while John Neufeld and Conrad Pope assisted Williams for most of the 1990s up until the late 2000s, when the composer opted to turn his detailed sketches directly to Mark Graham and his music prep team.

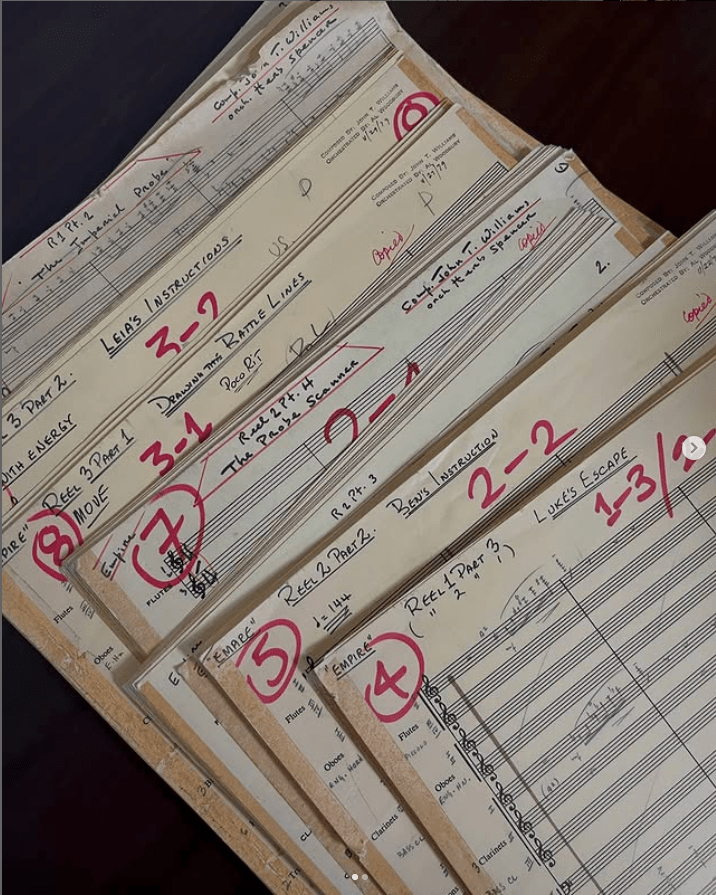

Williams said that the role of orchestrators on his scores was a stenographic assistance which would save him of the very laborious and time-consuming process of preparing the full score, which is a luxury a film composer cannot allow as the writing schedule is, more often than not, incredibly tight. Just to give an example: the 800-page score for Star Wars was written in just six weeks between January and March 1977 and needed five orchestrators (including Williams himself) to be completed in time for the scheduled recording sessions in London. Williams always retained the authorship on his orchestrations, as it’s music conceived orchestrally already from its inception. Starting with the score of Lincoln (2012), Graham and his team extracted the individual parts directly from Williams’ sketches, establishing a new and more efficient working method.

Graham has worked for Williams on countless projects and he is one of the very few people in the world who have an almost daily access to him and his work, therefore acquiring a truly unique insight into the man and his music. In addition to work on film projects, Graham oversees the preparation of Williams’ concert music and manages the archive of a great deal of the composer’s manuscripts and scores, which are stored at JoAnn Kane Music’s library in Glendale, California. Having assisted Williams from the late 1990s, Graham saw the technological (r)evolution that also impacted score preparation, which went from the tactile analogue world of film reels, tape splices and pencil scores to the virtual realm of computers, ProTools and digitally engraved scores, but the substance of his work for the Maestro remained virtually the same.

In addition to his work for John Williams, Graham worked as orchestrator and conductor for such composers as Alan Silvestri, John Debney, Alexandre Desplat and Theodore Shapiro. As head of music preparation, he was on an impressive series of successful films, including such all-time box office hits as Avengers: Endgame and Avatar: The Way of Water. He also worked as orchestrator and conductor for Robbie Robertson’s Academy Award-nominated score for Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon. The list of credits speaks for itself and it’s one of the most astounding anyone can have in the industry: Mark is an incredibly busy man working around the clock on multiple projects in both Los Angeles and London.

As the owner of JoAnn Kane Music Service, he supervised the preparation of dozens of live-to-picture concert projects, including many of John Williams’ films like the Star Wars and Harry Potter films, Jaws, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Jurassic Park, Superman and Home Alone, but also other crowd-pleasing favorites such as Back To The Future, Skyfall and The Princess Bride, for which he adapted Mark Knopfler’s electronic score for symphony orchestra.

Mark sits down for a rare conversation with The Legacy of John Williams to talk about the path that led him to become the leading music preparator in Hollywood and to his collaboration with John Williams, telling stories and anecdotes about his three decades of work for the Maestro and sharing the unique insight he collected over the years by being one of Williams’ closest and most trusted colleagues.

Mark Graham’s Official Website:

https://markgrahamcreative.com/

JoAnn Kane Music Service Official Website:

https://joannkanemusic.com/

List of musical excerpts featured in the episode (all music by John Williams except where noted):

. “The Scavenger” from Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015)

. “The Falcon” from Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015)

. “Avner and Daphna” and “Thoughts of Home” from Munich (2005)

. “The Court’s Decision and End Credits” from The Post (2017)

. “Getting Out the Vote” from Lincoln (2012)

. “Journey to the Island” from Jurassic Park (1993)

. “Clark Loses His Nerve” from Superman (1978)

. “Inner City” from Star Wars: A New Hope (1977)

. “The Potrait Gallery” from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2003)

. “The Knight Bus” from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2003)

. “The Adventures of Tintin” from The Adventures of Tintin (2011)

. Jerome Kern, arr. John Williams, “The Last Time I Saw Paris” from the album Johnny Desmond – Swings (1958); Orchestra conducted by John Williams

. Ray Henderson/Buddy DeSylva/Lew Brown, arr. John Williams, “The Varsity Drag” from the album Rhythm In Motion (1961)

. “March of the Resistance” from Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015)

. “The Days Between” from Stepmom (1998)

. “End Titles (Alternate)” from The Patriot (2000)

. “Helena’s Theme” from Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023)

. “Nice to be Around” from Cinderella Liberty (1973), version for violin and orchestra; Anne-Sophie Mutter, violin

. “Finale” from Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017)