As we were finally treated to the premiere of a brand-new Piano Concerto by John Williams, it seems only natural to look back at the composer’s output, both for the concert hall and for film, and to identify those pieces where the piano is the main character.

In the past, composers have often written pieces for their own instrument of choice, and that instrument was quite commonly the piano. Composers from Mozart to Shostakovich, have composed music for solo piano, for chamber ensembles featuring the piano prominently, and for piano and orchestra. Many composers were themselves gifted performers of their own piano works and of those of others. In former times, composing solo pieces for the piano (or providing reductions of works originally conceived for larger ensembles) was a good source of income. So it is no surprise that compositions for solo piano or small-scale ensembles with piano can frequently be found among many composers’ early works.

Yet Williams’ “instrument” of choice for his compositional efforts has been, almost from the beginning, the orchestra. His compositional output for solo instruments or chamber ensembles is rather small when compared to the orchestral one. And while he might not have been as prolific as Mozart, for instance, in writing concertante pieces with the piano as the main soloist, he did use his original instrument (when it felt right) in many of his film scores. Sometimes it’s just one of his “pets” (as he often refers to his favourite instruments and/or performers in the orchestra), and at other times there might be a cue or two that have a proper piano solo (sometimes a principal or secondary theme performed on the piano or themes expressly written for the piano), and on a few occasions a score of his might be, in fact, centred on the piano and be almost regarded as a piano concerto of sorts. As for his concert output, however, it was not until quite recently that he started to include the piano as the main character.

The following is an overview of Williams’ “piano works,” paving (in a manner of speaking) the road to his recent Piano Concerto.

Concert Works

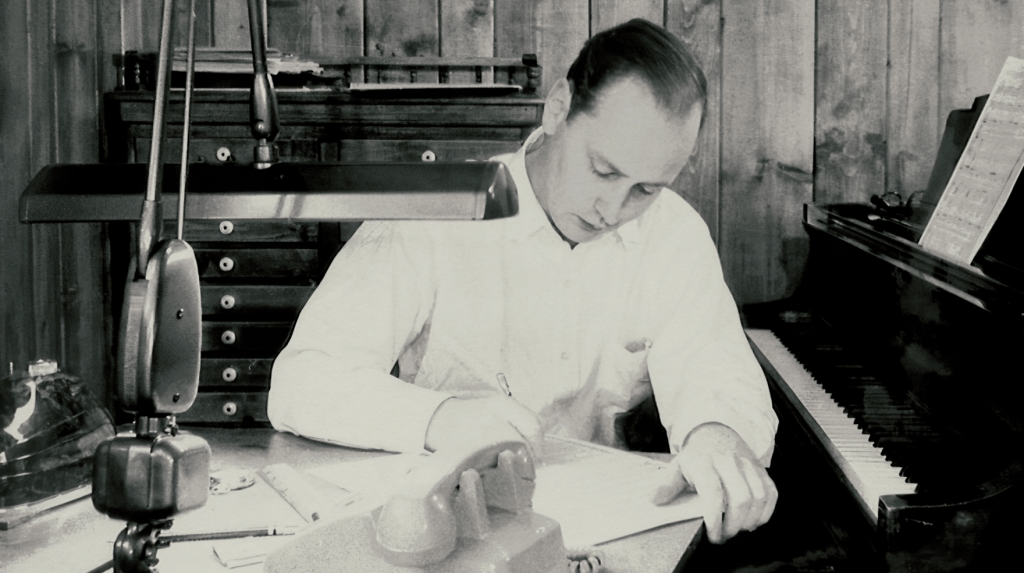

John Williams’ earliest compositional entry featuring the piano is also one of his earliest compositions of all. Back in 1951, he sketched a Piano Sonata that never became more than those sketches and was never completed or performed1. As with so many composers in the history of music, it was only natural that early attempts at composing pieces of his own would reflect his main instrument. By the late 50’s, as he was transitioning from a gifted session pianist to a full-time composer, his own little pieces found their way into some of the recordings he was making at that time. These are easy-listening numbers infused with the sounds of West Coast Jazz, featuring the composer on the piano who was still in his late 20’s, showing off both his composing and performing chops.

As far as concert works are concerned (and if we put aside piano reductions prepared from his orchestral scores for rehearsal purposes), the first such entry into the catalogue with the piano as a relevant voice comes up no sooner than 1998 with the hauntingly beautiful Elegy for Cello and Piano. Better known through the later version for Cello and Orchestra (first recorded by Yo-Yo Ma), the piece is based on a secondary theme from his score for Seven Years in Tibet (1997) as heard in the cue “Regaining a Son.” The genesis of the Elegy itself revolves around tragic deaths of the children of one of the violinists who regularly played on Williams’ studio dates. The composer recollected that “for the memorial service for little Alexandra and Daniel, a group of composer colleagues and I each contributed a small piece to mark this occasion, which was not only heart-rending, but also one that was suffused with a great deal of love.”2 For that occasion, Williams accompanied Los Angeles cellist John Walz. He would later refer to the tone of the Elegy saying “It can be a wish and a prayer for wholeness and forgiveness and so many other things… give birth of ideas and of feelings in life,”3 allowing for a more optimistic view of the piece. Cellist Bruno Delepelaire sees “this magic light through the whole piece,” being “much more meditative” than a sombre elegy like the famous Fauré one, adding that it elicits memories of “good moments with someone you love.”4

Nevertheless, this is not a piece for the piano to shine, as it just accompanies the cello that carries the heartfelt melody. Eventually, it has been the Cello and Orchestra version that has become more well-known. Yo-Yo Ma and Johannes Moser presented it as an encore, and both the late great Lynn Harrell and Bruno Delepelaire recorded it. The original version has also found its way into the repertoire, but not until last year a recording of it was finally released, namely the beautiful performance by Cecilia Tsan and Simone Pedroni.

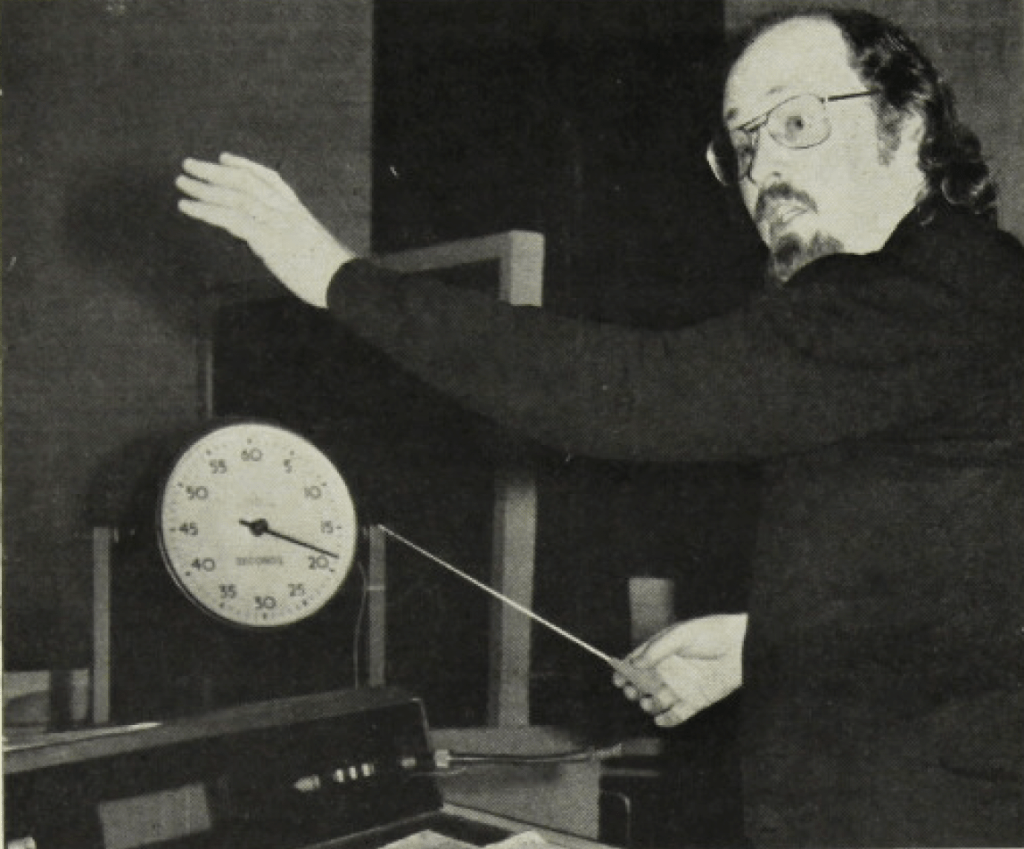

In 2003, as part of “Soundtracks, Music and Film: A National Symphony Orchestra Festival,” in Washington D.C., for which Williams served as music director along with Leonard Slatkin, the composer contributed a little piece for 4-hands piano, a mix of concert piece and film work. The little piece, first performed by Slatkin and Williams on the January 25th concert, served to exemplify the needs of synchronization between music and image, while providing a look back to earlier days of cinema. The composition clearly draws from the kind of music one would listen to in the 1920’s, from the piano accompanist during a film projection, mickey-mousing around the action on-screen by the likes of Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and the Keystone Cops. Williams would perform it once again, during the Boston Pops’ spring season of that year, with the orchestra’s pianist Bob Winter. That performance would reach a wider audience beyond the walls of Symphony Hall, as it was broadcasted as part of the Evening at Pops series.

Later on the decade, another chamber-sized piece included the piano, though this time written for a quartet of highly gifted soloists that included the Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Montero (known for her virtuosity and strong improvisational skills). Composed for Barack Obama’s first presidential inauguration, Air and Simple Gifts (2009) used the same instrumentation as the seminal Quatuor pour la fin du temps by Olivier Messiaen. Both are works about hope, even though they couldn’t stand more apart in their sonic worlds. Williams’ quartet, surely more modest length-wise, is still a piece that aptly combines virtuosity and sobriety with a sense of austerity and the unshakable hope for a brighter future. The piece was first presented live by Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma, Anthony McGill and Gabriela Montero on January 20, 2009 in Washington, D.C.5 and soon became a regular in American music chamber recitals.

The first long form piece completely focused on the piano had to wait a few more years, but when it arrived, it didn’t need to share the attention with any other instrument. As it happened, champion of contemporary piano music and a regular Williams session pianist for about a decade (starting with Munich in 2005), Gloria Cheng was preparing a recital to be held during the Tanglewood Festival of Contemporary Music in the Summer of 2012, focusing on the Los Angeles-Tanglewood connection. It included music by composers Harrison Birtwistle, George Benjamin, Oliver Knussen, John Harbison, Bernard Rands and Esa-Pekka Salonen. At the time, fearing Williams would decline due to his busy schedule, all that Cheng asked for was a single page of music. Williams did comply:

The resulting piece, Conversations I. Phineas and Mumbett, marked the beginning of a larger composition for solo piano by Williams and that of a whole new project (which was to focus on piano music by various Hollywood composers including Bruce Broughton, Don Davis, Alexandre Desplat, Michael Giacchino and Randy Newman).

Premiered on August 10, 2012, at the Seiji Ozawa Hall, Tanglewood, as an encore to the recital, the Williams piece reflects on what would be a conversation between jazz pianist Phineas Newborn Jr. and Elizabeth Freeman (also known as “Mumbett,” a slave in Great Barrington who successfully sued for her freedom). While not being jazzy, it somewhat brings to life that world of smokey jazz clubs during the late hours of the night. Appropriately, Williams wondered how “this perfectly nice girl from New Jersey knows how to play this music. She must have wandered into some bars her parents didn’t know about.”6

But just as the afore-mentioned single page of music became an approximately 5-minute piece for solo piano, that same piece became the first movement of a four-movement composition called Conversations. “The first movement was supposed to be the only movement. [As for the] following movements, I think he just said ‘I have another idea for you’, and then, three months later, ‘I have another idea’. I think this was during a hiatus from his film writing, when he had some free time. He wasn’t really busy and he just kept at it. He simply got into the idea of writing a solo piano piece.”7 Again, none of the “conversations” try to directly mimic compositional or performing trends and styles, they are not jazz per se, even though the more careful listener might spot some sort of references to the musicians portrayed. “Pianistically speaking, [John] never asked me to play in the way Duke Ellington or Phineas Newborn played… I think he just embedded the licks and stylings of those composers into the music, then set me free to make of them what I would.”8 The music of these jazz giants “is there in such an imaginatively abstracted result.”9 Eventually, Conversations became, along with Bruce Brougthon’s “Five Pieces for Piano,” the motto for another project (as mentioned above), a collection of commissions to composers strongly associated with Hollywood, namely Michael Giacchino, Don Davis and Randy Newman. (The project also included a piece by Alexandre Desplat originally written for pianist Lang Lang).

Conversations might have come as a bit of a shock to those fans who had longed for a solo piano (or piano and orchestra) piece in the same vein as his most famous film scores. And even if one can picture these conversations in a smoky jazz club, the piece itself remains quite abstract, without cantabile themes to hold on to. It might be a bit more difficult to get into it as it certainly was for Cheng to learn it: “The virtuosity with which he taps into such heterogenous jazz styles is almost dizzying, and for me as a classically trained, hopelessly-unable-to-improvise pianist, they provided a welcome stretch.”10

But the rewards lie within repeated listening, which will provide a clear understanding of Williams’ unmistakable voice despite the more abstract nature of the work.

And while fans eagerly waited for the recording of Conversations that was to be released by Harmonia Mundi in 2015, a surprise arrived on July 1, 2014, in the form of a Scherzo for Piano and Orchestra written specifically for superstar pianist Lang Lang as part of a concert celebrating Chinese conductor Long Yu’s birthday. The piece had been announced just a few weeks earlier and marked the first time a non-US musical institution had commissioned a concert work from Williams — as well as the first time one of his works received its world premiere outside of the United States.

The first performance took place at the Poly Theatre, Beijing, with Lang Lang performing the solo part and the China Philharmonic under Long Yu. Just a few days later, on July 4, during the “Music in the Summer Air” festival (the actual commissioning institution), a new performance of the piece could be experienced, this time with pianist Li Jian and the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra; Long Yu was the conductor again.

The piece can easily be described as percussive as the soloist bangs on the keyboard frantically, punctuated by timpani and blasts from the orchestra. More angular and abstract, just as Williams’ other long-form concert works, the Scherzo lasts about 10 minutes and begins with a dialogue between timpani and piano over the piece’s main thematic idea. The orchestra then takes over with heraldic fanfares for a short moment, and soloist and accompanist “fight” for their place in the piece. Midway through it, the piano gets its cadenza, mysterious and again abstract in tone. The orchestra returns and keeps up its dialogue with the soloist until a brilliant and rejoicing wannabe coda is reached, but is then interrupted by the soloist for one final statement, after which a blast from pianist and orchestra brings the fiery scherzo to an end. The premiere was recorded and released digitally on China Recording Association CP54-462, but there have been no new performances or studio recordings available since.

At the time of its release, many admirers wondered how this Scherzo could be the central movement of a Piano Concerto. After the success of Conversations and the “Montage” project, Williams eventually added an introduction to it: “A fresh piece that he needed in some way to work with the preexisting piece (…) and he had to connect them somehow. (…) Its tone is nocturnal, very pensive, very internal, reflective, poetic.”11

While quite different in tone, both pieces connect perfectly and represent their very different dedicatees: “The Scherzo truly channels Lang Lang, especially the original ending, and it highlights Lang Lang’s sensibilities; I feel like John wrote the Prelude in a way that highlights mine.”12 The newly expanded piece was finally premiered at the Palau de la Música, Barcelona, on June 21, 2021, with Cheng accompanied by the Orquestra Simfònica del Vallès with Marc Timón conducting. (Almost everyone was wearing masks due to the protective measures surrounding the Covid-19 pandemic). That same pandemic prevented the work to receive its world premiere in the United States – the US premiere took place on June 4, 2022 in Albany, with the Albany Symphony under Alan David Miller (another strong advocate of new music).13

Even though the piece was to be recorded shortly after its US premiere, the work remains unreleased. Nevertheless, these two pieces, Conversations and Prelude and Scherzo, clearly set the stage to the ambitious Concerto for Piano and Orchestra that debuted at Tanglewood last July.

Film Works

Williams’ film output is gargantuan and filled with so many masterpieces of the genre as few other careers in film music are. Having that said, a survey of his piano writing for this medium is bound to miss several examples the reader might find it would be obvious to include. Some might have been forgotten within such a large catalogue, others might have warranted a higher degree of attention from this writer… Either way, the piano being Williams’ instrument, it became the main musical voice in just a few film scores. Always a master at orchestration and finding the right musical mood for a film, he used the piano just when he felt it was really needed, either for a whole score or just for specific moments of it.

The use of the piano in his film music can be heard right from his early days writing for television, often in the jazz vein prevalent of the time. Nevertheless, those aren’t piano and jazz orchestra pieces or scores. In both the music he wrote for the M-Squad series (1959) and his big break the following year with Checkmate, the piano is either part of the orchestral texture or just one of the soloists, joining other members of the band in presenting the material. As examples, one could refer to “The Chase” from M-Squad or “The Isolated Pawn” from Checkmate. In both cases, the piano introduces the thematic material before being picked up by other instruments for further development.

Curiously enough, for a single released some time later, Williams recorded a new arrangement of his cue “The Black Night,” coupled with a totally new composition called “Augie’s Great Piano.” For a long time, these could only be found on said single release from the 60’s, until they were included in a compilation released by Blue Moon Records in 2015. For both these pieces, the piano was the main soloist.

These early crime shows in Williams’ career were of course styled after the sound created by Henry Mancini, Elmer Bernstein and others for this kind of stories. And he learned about them first hand as he was often the session pianist for the elder composers’ scores, just as he would play the piano himself on some of his own compositions.

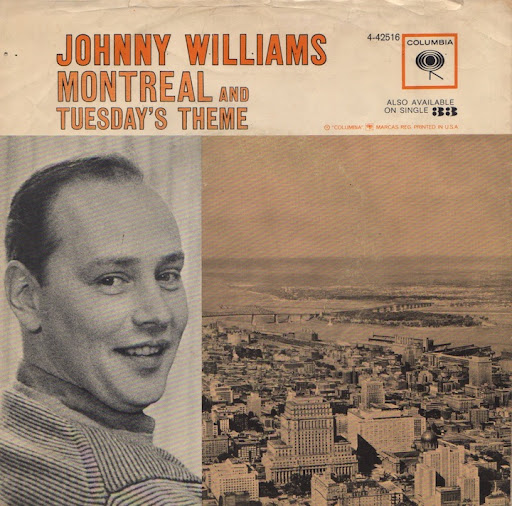

One oddity of those early 60’s scores relate to a theme Williams seems to have been rather proud of. For Bachelor Flat (1962), one of the main themes, portraying the female lead, was named after its actress Tuesday Weld. The composer later recalled that “the important thing about that picture is not that it was my first but that it was Tuesday Weld’s.”14 On the score, the theme is played by the orchestra, and even though the film recording was only released in 2008 (Intrada Records Special Collection Vol. 83), Williams liked the theme enough to have it recorded twice. The first, a full-fledged arrangement for orchestra (with some colouring from the piano) came out on Columbia as a single by “Johnny Williams and His Orchestra” (Columbia Records 4-42516, released on CD on Blue Moon Records BMCD 858).

The second one is a more interesting arrangement and features the piano as the main soloist. Arranged for Williams’ close friend André Previn, this was included in Previn’s Music of the Young Hollywood Composers (RCA Records LSP-3491, available digitally here) and clearly shows the ability of a young Johnny Williams in writing for the piano as a main musical voice. The album includes another Williams-composed track, “A Million Bucks” from Checkmate. These aren’t film works per se but reworkings of film themes, a trend that would be a constant throughout Williams’ career. These early examples are surely worth exploring within the context of his pianistic output.

Another forgotten film from his early days was Diamond Head (1963). A vehicle for James Darren, it was Williams’ first film score to be released alongside the film’s theatrical run. Included is the jazzy cue “Catamaran,” a piece that starts with a long piano solo before the entrance of the orchestra that keeps supporting the soloist.

Throughout his long film career, the piano is showcased as a concertante instrument on only a few occasions. For a large amount of its use within Williams’ film scores, it is another colour the composer has at his disposal, to be used effectively when needed. Two different examples of how the piano shows up within the score can be found on None But the Brave (1964) and How to Steal a Million (1966). For the former, the only film directed by Frank Sinatra, Williams makes use of the piano in some sombre, militaristic action cues, with the instrument used in percussive fashion and buried within the orchestral texture. The latter, directed by Hollywood luminary William Wyler, uses the piano in its main title as part of the orchestral texture. It does not concertize but rather compliments the orchestration with its own character. The same can be said of other cues like “Two Lovers Theme” or “Nicole,” where the piano is just another voice of the orchestral palette, providing support for the instruments that are indeed front and centre. With more prominence and what, in retrospect, may seem an old precedent to the more recent pianistic concert pieces, “The Prowler” uses the piano to create an eery, mysterious and a bit ominous atmosphere. So, these two scores are not only worth mentioning because of their high-profile directors but also because they mark early instances of Williams’ use of the piano in film scoring. These early works show a composer already fully aware of the possibilities of the orchestra and its instruments, including the piano. None But the Brave marked another “Tuesday’s Theme-” like situation. A solo piano rendition of the theme, performed by Williams himself, was recorded shortly after the score sessions for a single release that never happened. We eventually got this performance when the whole score was finally released (FSM Vol. 12 No. 12). Solo versions of the main theme, both within the film score or as a stand-alone cue on the soundtrack album, would continue to happen all through Williams’ film career, with a recent example being Lincoln (2012).

During the 60’s, as Williams scored several comedies with easy-listening jazzy scores (somewhat modelled after Mancini’s own efforts of the time), the piano would show up in the capacity described before of complementing the orchestral palette, with occasional spots of greater prominence. An example is the song “Big Beautiful Ball” from Not With My Wife, You Don’t! (1966). Lyrics author Johnny Mercer provides a witty vocal performance, accompanied by piano before the orchestra takes up for the second half of the song.

From the following year, the score for Fitzwilly might be mostly remembered because of the song “Make Me Rainbows,” which has since become a minor jazz standard. (The lyrics are by Alan and Marilyn Bergman). It’s another forgotten comedy of its time (with the expected score à la Mancini) and the piano shows up for some small spotlights in jazzier cues like “Lefty Lovies Love Life” and “Sampson and Delilah.” A more suspenseful cue, “Juliet’s Discovery,” uses the piano in similar fashion as “The Prowler” from How to Steal a Million.

One must take a closer look at the following decade to finally have scores that make more use of the piano, either as a solo voice or as an accompanying one, and where the instrument is heard throughout the entire score. When regarding the early 70’s, with some intimate dramas dropping on the composer’s plate, the use of the piano surely looks like the obvious choice as the main musical character.

By the early 70’s, fresh from work on large musical projects15, two trends were going on in Williams’ film career: scoring large crowd-pleasing pictures (that would eventually lead to Steven Spielberg and the mega-success of Jaws) as well as intimate dramas and maverick director’s productions.

It was during a pause while working on Fiddler on the Roof that Williams would score a television adaptation of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1970), directed by Delbert Mann. A score that the composer has often referred to as being very close to his musical heart, Williams adapted it into a three-movement suite for his first season as principal conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra. But the original score used a smaller orchestra and for the main and end titles, relied on the piano to carry the main melody.

Robert Altman’s Images (1972), the tale of a woman suffering from schizophrenia, remains Williams’ most experimental work for film, with the use of unusual percussion and vocal effects performed by Stomu Yamash’ta. The eerie sounds represent the main character losing her grip on reality. On the ‘other side’, namely in the real world, the music is tonal and centred on piano and strings, with the composer doing all the piano playing. The score, recorded in London, marked Altman’s and Williams’ first feature film collaboration, even though the two friends had already worked together for television. A test pressing of the Images score was prepared at the time of the film’s production, but it wasn’t released until decades later in 2007. One of the highlights of the piano-driven section of the score is the haunting cue “In Search of Unicorns,” combining the more melodic part of the score with the wild avantgarde one:

Williams and Altman reunited once again for the director’s next project The Long Goodbye (1973). Just as with Images, The Long Goodbye is a rather unique score, both in Williams’ career and, in a broader sense, in the history of film music. There is only one theme that is both used in a diegetic and non-diegetic manner all throughout the film, a sort of “theme and variations” approach. These variations show up in all possible circumstance and situations, whether played on the radio, by a marching band or even as a doorbell. While the piano isn’t centre stage as a solo voice, it still has a very important role in several jazz trio presentations of the theme. Several singers perform that theme as a song, and for the most part the accompanying pianist was Dave Grusin, but on one occasion, Williams himself sat down at the piano for some playing:

Unfortunately, the Altman/Williams collaboration came to a halt due to dramatic events in the composer’s life, even though Altman and he remained friends. Williams’ name was associated with other Altman projects once or twice after The Long Goodbye, and one can only wonder what those films would have compelled Williams to write, considering the creativity and diversity on those previous projects.

Going back to 1972, the other piano-oriented score Williams composed was for a film directed by Martin Ritt. As a director who came from the theatre, Ritt strongly felt that music was to be used very moderately in his films. For Pete’n’Tillie (1972), his first collaboration with Martin Ritt, Williams provided a beautiful score centred on the piano, which carried a bittersweet melody that perfectly encapsulates the drama on the screen. Even though this score runs only for about 20 minutes, for the film even less was used, no more than half of it.

Ritt and Williams collaborated on two more occasions: For Conrack (1974), Williams provided a short, folksy score (with a little honky-tonk piano element), and for Ritt’s final film Stanley and Iris (1990), another drama dealing with the difficulties and traumas of adulthood. Williams returned to a sound world similar to their first collaboration and once again used a smaller sized orchestra. While for Pete’n’Tillie the piano was the main solo voice, the later score features solos for several instruments, including flute and trumpet. Nevertheless, it’s the piano that we first hear before the flute takes on the main thematic idea. Throughout the score there are several occasions for the piano to shine, but surely the first part of the “End Credits” is the highlight in that respect.

Returning to the 1970’s, Williams provided a last-minute replacement score for The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing (1973). Directed by Richard Sarafian and starring Burt Reynolds and Sarah Miles, this was a troubled production from the start. Michel Legrand, fresh from his success both with French and Hollywood film songs and score, provided a quasi-improvisatory score that was deemed inadequate for this odd western. Just the day after Legrand’s recording sessions, Williams was signed on to provide nearly 40 minutes of music in just a few days’ time16. 50+ years later, one of the few things the film might be remembered for is the song that eventually emerged from the main theme of the score. Paul Williams provided lyrics for it, and the song “Dream Away” ended up being recorded by none other than Frank Sinatra himself on his comeback album “Ol’ Blue Eyes Is Back” (1973). Nevertheless, it is on the actual film score, and over the main and end titles the piano is used where it supports the presentation of the main material from the score.

One final piano-oriented score from the early ‘70s was the college drama The Paper Chase (1973). It’s the piano that carries the main melody through several variations of the main theme. While the film, directed by James Bridges, is today remembered only by very few cinema lovers, back then its theme was even picked up by the popular piano duo of Ferrante and Teicher, and lyrics by Larry Weiss were added for a single sung by John Davidson.

The score, finally released on CD in 1998, mostly uses that main theme, even though the highlight is “The Passing of Wisdom,” an atmospheric cue featuring harp and woodwinds and dropping the piano as solo voice. The score rounds up with some baroque period pieces, arranged by Williams and representing academia, and a couple of source cues in line with a more generic ‘70s pop sound. For those, Williams would sometimes use the piano as part of the rhythm section to replace the more usual sound of the organ, a typical instrument of those days.

Speaking of period pieces, for the romantic drama Cinderella Liberty (1973) Williams wrote his music in a style redolent of the early ‘70s. The beautiful cue “A Baby Boy Arrives,” features a big piano presentation of the theme after a heart-wrenching harmonica solo performed by the great Toots Thielemans.

With the arrival of bigger projects in the following years, a kind of lusher orchestral sound was required which left the piano to only a few cues where its more intimate approach was deemed appropriate. Two examples show up in consecutive years: in 1974, Williams scored another disaster movie, reuniting with director Mark Robson for Earthquake. For this, we can hear the piano used in a more modernistic approach in cues like “Cory in Jeopardy.” Apart from that, we are treated to a beautiful rendition of the main theme in “City Theme.” The following year, the composer would score one of Clint Eastwood’s earlier self-directed films. A rather forgettable, poorly aged thriller, The Eiger Sanction was based on a novel by Trevanian about an art teacher turned assassin. The jazzy main theme receives several variations throughout the score, many of them with prominence for the piano. Like in Earthquake the piano is also used in a more modernistic manner in cues like “The Microfilm Killing” or “Up the Drainpipe.” Somewhat reminiscent of his work in Images, this kind of approach has become one of the composer’s ‘tools’ for suspenseful or violent scenes.

Right on the verge of global success (or should one say, intergalactic success) brought by Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (both 1977), Williams scored the thriller Black Sunday. Directed by John Frankenheimer, who often worked with composer Jerry Goldsmith, the film follows the plot of a terrorist group to make a Goodyear blimp explode over the stadium during the Super Bowl game. The music is, for the most part, tense and ominous. Williams often uses the piano to help carry some of the motivic material, using those motifs as a sort of idée fixe, that builds tension and creates suspense. The following exemplifies such use of the material, with the piano providing a groove under the woodwinds and occasional percussion:

Williams assignments for big budget films required huge symphonic scores from the mid 70’s on. It would be a decade until Williams scored another adult drama that used the piano as its main voice. Until then, the piano would remain very much present in the already discussed ways. In 1980, for the highly awaited sequel to Star Wars, Williams composed the mechanical “The Battle in the Snow,” echoing his love for 20th-Century Russian composers. A percussive tour de force, it accompanies the attack on the Rebel base by huge mechanical armoured Imperial walkers and clearly translates into music the dreadful events by punctuating it with barbaric piano clusters.

It’s another one of Williams big symphonic achievements that has yielded one of his most memorable piano pieces for film. For Spielberg’s E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Williams used the piano as part of the texture on a secondary motif that relates to the mystery of the unknown. It is an unsettling little musical idea that eventually disappears as boy and alien build a friendship. 17 Yet it is on an album track that the piano really shines. “Over the Moon,” based on a theme that on film is only heard performed by the whole orchestra, is a 2-minute concertino for piano that becomes a concert miniature. As such, it goes unused in the film, but as an album arrangement has been one of its highlights as brilliantly performed by Ralph Grierson.

Although “Over the Moon” was a unique arrangement, the big piano solo can be heard on screen during the first part of the End Credits before music from the final reel of the film is reprised.

Just a few years later, the Spielberg-produced anthology series Amazing Stories (1985/87) contained not only Williams’ scores for this project, but also the main and end credits music. For the End Credits (a cue which was used throughout the two seasons), Williams provides a version of the series’ theme for piano and orchestra reminiscent of “Over the Moon.”

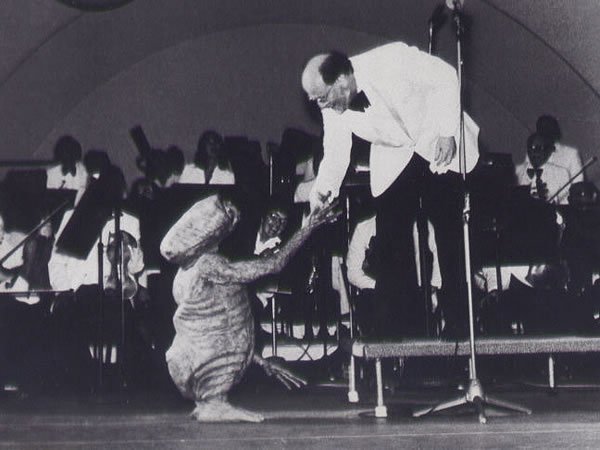

A somewhat similar approach would happen again with the devilish “The Tennis Game” from The Witches of Eastwick (1987) . In this cue, the piano is the main voice (the virtuosic solo is performed by famed studio pianist Chet Swiatkowski) and accompanies the fun sequence with a spirited touch, providing another wonderful miniature for piano and orchestra. Williams himself performed the virtuoso piano part in 1993 during a rare live performance by the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Seiji Ozawa.

Several cues from Empire of the Sun (1987) also make use of the piano in a leading role, either eerily, like in “The Return to the City,” or when depicting chaos in “The Streets of Shanghai.” With its percussive use of the keyboard, the piano adds to the overall texture of the score. Additionally, a couple of Chopin pieces were recorded and used.

After a decade of larger-than-life blockbusters, Williams’ assignments tended to return to smaller scale dramas from the mid-1980s onward. Right after his two 1987 films, the composer was called to write a replacement score for The Accidental Tourist (1988), directed by Lawrence Kasdan after a novel by Anne Tyler. Revolving around an eccentric travel guides’ author who mourns a lost child, Williams provided a deeply intimate work, scored for piano and small sized orchestra. While apparently monothematic, the theme is actually built on several motivic ideas that are assigned to different aspects (both tragic and hopeful) of the story. The drama unfolds until the climatic “A New Beginning” underscores the protagonist finally finding peace and love.

Not long after The Accidental Tourist, another adult drama would have the piano as its main soloist. For Alan J. Pakula’s court drama Presumed Innocent (1990) about treason of all kinds and with plot twists at every turn, Williams wrote another score focusing on the piano accompanied by small orchestra18. Unlike The Accidental Tourist, this is music devoid of hope and sense of closure. There is no love theme – instead, Williams calls what would have been a love encounter “Love Scene,” refusing the listener the resolution a proper love theme would bring. It points out that what we see onscreen is just a carnal encounter empty of any meaning or feeling. The theme is a tortured one, carried by the piano, with occasional interjections of synthesized chords, a device Williams often associates with darker feelings.

In between these scores, Williams’ use of the piano remains congruent with what one can find in his tool box for filmmusic: He conjures an ominous presence in the atmospheric and disturbing cue “Cua Viet River, Vietnam, 1968” from Born on the Fourth of July (1989) or in several passages from the more peaceful Always (1990). While on the latter, the piano and other keyboards are used for effect in the sequences referring to ‘heaven’, there is a beautiful solo part that opens the cue “Pete and Dorinda.” As we catch the couple in the middle of the evening, the music seems to start in the middle of a dream, providing the most intimate feeling.

Even though Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991) marked a departure from Williams’ usual modus operandi, the music remained very much his own. For this project, the director asked the composer to create a collection of cues that he would then use to get a sense of rhythm for the film, enhancing the documentary feeling that Stone wanted for the film. Williams provided set pieces that make use of the piano in his already well-established style: there is a piano version of the main theme, but the instrument is also used in a persuasive and supporting manner in pieces like “The Motorcade” or “Garrison’s Obsession”.

Up to that point, film scores by John Williams with a strong presence of the piano were the exception. Still, obvious trends, as exemplified before, continued throughout the years. Among them were the use of piano solos in jazz-infused cues. “Banning Back Home” from Hook (1991), is vibrant piece for jazz combo, somewhat influenced by the music of Dave Grusin. Beautifully performed by the late Mike Lang, it sets apart the real and serious business world of Peter Banning from the fantasy realm that follows (scored by full orchestra almost non-stop).

This approach connects to the stylistic option of writing a set of three source cues of jazzy lounge music which diegetically score the meetings of newspaper moguls in Spielberg’s The Post (2017), accompanied with a jazz combo consisting of piano, guitar and drums.

The other use of the piano that continued from earlier scores was the presentation of the theme or main themes in moments of special meaning, usually associated with situations of reflection. Both Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List from 1993 end like that. In the former, the piano scores a short epilogue before leading into the end credits suite, providing a tender moment of reflection on the risks of using technology just for the sake of technology itself. In the latter, the piano underscores the first half of the end credits. This solo was performed by Williams himself and honours all the ones whose lives were lost during those terrible times with great simplicity and just as great emotion. This approach continues to his more recent scores. A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) has a few moments where the piano comes to the front, most notably in the emotional final scene of the film when robot child and human mother reunite.

For the sci-fi thriller War of the Worlds (2005), Williams wrote violent music that matched the terrifying action on screen. At the film’s finale, when the family reunites, a sombre meditation for piano and orchestra brings the film to a close. Munich (2005) provides a beautiful cantilena-like passage for its End Credits suite, performed by the great Gloria Cheng, who had to learn it overnight. For yet another Spielberg film, War Horse (2012), we are treated to a version of the main theme performed on solo piano when near the end of the film, the main characters travel back home after the horrors of war. Set against the backdrop of a wide landscape with only our equestrian and human protagonists crossing it all alone, the solo piano provides the kind of needed respite and reflection before the emotional reunion with their family. Williams understands how to best use the piano as an expressive partner in conjunction with powerful images and feelings, thus enhancing the meaning of these scenes considerably.

For Spielberg’s adaptation of Roald Dahl’s The BFG (2016), Williams harkened back to their earlier collaboration on E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial. In the 1982 film, we see the little lost alien through the eyes of a child; this time the alien is a friendly visitor from the land of giants who kindly distributes good dreams to children. While less operatic than the earlier film, this story revisits the innocent way children face the unknown, seeing it as pure magic. For the finale, Williams again trusts the solo piano with a beautiful emotional rendition of little Sophie’s theme, one that encompasses the friendship with her Big Friendly Giant.

Opportunities for scores like The Paper Chase, Pete’ n’ Tillie, The Accidental Tourist or Presumed Innocent were but a few in in these past three decades, even though Williams moved toward scoring more intimate films. The remake of Sabrina (1995) provided such an opportunity. The opening of the film starts with a dream-like theme for solo piano that is eventually picked up by the whole orchestra. While not a score for piano and orchestra, as some of the previous ones, it still uses the piano quite abundantly. Even though two other pianists were present during the sessions, Williams himself performed the solo that opens the album.19

In 1998, Williams scored Spielberg’s war drama Saving Private Ryan and the more intimate film Stepmom, directed by Chris Columbus. Both scores show great restraint, and the latter is close to being a chamber piece for guitar (performed by Christopher Parkening) and small orchestra, with some embellishment from synthesized sounds. On several occasions, the piano makes an emotional appearance.

For Frank McCourt’s memoir Angela’s Ashes (1999), Williams wrote a sort of ‘concerto grosso’ with solos for several instruments: cello, oboe, harp and piano. The session pianist was Randy Kerber, and he provided truly sensitive performances. While it should be noted that the piano phrase on the opening track was performed by the composer himself, I’m always drawn to this beautiful little passage that – with great sensibility – encapsulates the suffering and tragedy (but also hope!) of the McCourt family:

Kerber would solo on the aptly titled “Jazz Autographs” from The Terminal (2004). It’s the story of a man stuck at JFK’s International Airport who attempts to collect one final jazz autograph from Benny Golson, and this version of the theme fully encapsulates his love for jazz and the longing for home20.

For Spielberg’s adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s novella Minority Report (2002), Williams’ palette was vast, using the orchestra in many and diverse ways that fitted the needs of the story. Hardly a discrete score (nor a pianistic one), it still has some moments of reflection, namely when it comes to the music associated with Sean, the missing child of the film’s protagonist. “Sean’s Theme” is performed by the piano on several occasions.

Starting a new decade, Spielberg embarked on directing his first animated feature in what was expected to be a trilogy co-directed by Lord of the Rings’ Peter Jackson. Unfortunately, The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn (2011) failed to grab the interest of audiences, and so future films were discarded. Williams provided a high-octane adventure score much in the same vein as his Indiana Jones scores. For Tintin’s pet dog Snowy, Williams created yet another adventure-filled theme with insane piano runs that clearly translated the never-stopping adventures of our heroes into music:

In the 2010s, a quick succession of film assignments allowed for the piano to be more prominent. In Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012), the biopic on the sixteenth president of the United States, several themes were played both by the orchestra and by the piano. Be it the inspirational “The American Process,” the elegiac “The Blue and the Grey” or the score’s centre piece “With Malice Toward None” – they all received eloquent and delicate versions for the piano. Quite frequently, the music reflects on the complex nature of Abrahm Lincoln’s character, providing further subtext for the film. And when the piano alone is speaking, then Lincoln’s more intimate nature is best conveyed to the audience – they are moments when music tells us what images can’t.

The following year, almost by surprise, Williams scored Brian Percival’s The Book Thief. Williams was apparently drawn to the film after reading the novel by Markus Zusak upon which the film is based. As with Lincoln, the film provided several moments for the piano to speak for itself. And just like on so many other occasions, for the emotional finale, a beautiful cantilena-like presentation of one of the main themes was used to underscore this sort of short epilogue, featuring a duo between piano and harp.

It should be pointed out that both scores for Lincoln and The Book Thief had piano folios released and that those selections were arranged by Williams himself. Pianist extraordinaire Simone Pedroni expanded upon the Lincoln piano arrangements and released a CD recording in 2017. He also performed it extensively, as well as the piano arrangements of The Book Thief.

The third and final in this string of scores from the 2010’s was for another Spielberg film, The Post (2017). Besides the source pieces already discussed, one of the central musical ideas reaches its most poignant moments when performed on the piano.

Just as Williams, who in his twilight years finally composed a Piano Concerto, the instrument of his youth, did Spielberg turn to the more intimate drama of his own past. For The Fabelmans (2022), Williams fulfilled his own prophecy of how “it could be just as interesting to write a ‘Satie-like’ miniature score which is ten minutes long. That can be a jewel in the hands of a master (…)”21

The score is filled with the love for his old 88-keys friend, mimicking the passion for performance of one of the main characters. The music is small and intimate and scored for a chamber-sized ensemble with piano and some occasional celesta and guitar. And it has the same kind of emotional depth and intimacy that Satie’s piano music achieves. A great deal of the music heard in the film, while recorded by Williams and Los Angeles Philharmonic’s principal pianist Joanne Pearce Martin, is by other composers, including one of Satie’s Gymnopedies. These selections were mimicked on-screen by actress Michelle Williams, who portrays an amateur classical pianist. Williams’ score blends all that, and the Satie relation goes even further: the aptly French-titled cue “Reverie” (day-dreaming) perfectly channels the delicate and often transcendental music of Erik Satie.

For the time being, The Fabelmans is the final project in a tremendous creative collaboration between two amazing artists and close friends. As we are told that John Williams, despite his health setbacks of recent, is still writing new music, one can only look forward to what still might be in store and if any more piano-centred music will come along. Even if it doesn’t, while looking back from the vantage point of such a long and distinguished career, the piano music of John Williams is just as rich, varied and filled with emotional depth as that of all the composers from past eras, both classical or jazz, that Williams so much reveres.

A very special thanks to Markus Hable, for all the assistance and proof reading.

- “John Williams is new Pops Maestro: A Musician’s Musician” by Richard Dyer, The Boston Globe, January 11, 1980 ↩︎

- Composer notes on the published score, Hal Leonard #HL 04490844 ↩︎

- John Williams while addressing the audience during his Berlin Concert, October 16, 2021 ↩︎

- Bruno Delepelaire interviewed by Stanley Dodds, Berliner Philharmoniker’s Digital Concert Hall, October 2021 ↩︎

- First live presentation is more accurate than performance as, due to low temperatures, this group of superstar musicians had to mimic their playing, syncing it to a recording made a few days earlier. The actual premiere took place in Pittsburgh, on January 23, with Montero and members of the Pittsburgh Symphony Andrés Cárdenes (violin), Anne Martindale Williams (cello) and Michale Rusinek (clarinet). ↩︎

- John Williams quoted from the Montage documentary, 2016 ↩︎

- Gloria Cheng to Maurizio Caschetto, 2025 ↩︎

- Idem ↩︎

- Ibidem ↩︎

- Gloria Cheng, quoted in Caschetto, The Legacy of John Williams, 2018 ↩︎

- Gloria Cheng to Maurizio Caschetto, 2025 ↩︎

- Idem ↩︎

- The world première was planned to occur at Albany, NY, with David Alan Miller conducting, but the constrains created by the pandemic, led to the premiere taking place in Barcelona. ↩︎

- “Where is John Williams coming from?” by Richard Dyer, The Boston Globe, June 29, 1980. Williams misremembered as Bachelor Flat wasn’t his first feature film. ↩︎

- Williams served as music director for the big screen adaptations of the musicals Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1969) and Fiddler on the Roof (1971), earning his first Academy Award for his work on the latter. ↩︎

- Williams wrote the music and recorded it in less than a week. ↩︎

- Two decades later, for another Spielberg film, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Williams would make similar use of the piano. ↩︎

- Just like with The Accidental Tourist, the orchestration called for the use of synthesizers. Instead of using to make the ensemble sound larger, it was used to achieve disturbing and ominous sounds, a device the composer would keep on using to portray bad deeds by contemporary villains of sorts. ↩︎

- Williams only performed the solo piano section that lasts roughly two minutes. All the rest was performed by pianists Chet Swiatkowski, Michael Lang and Randy Kerber.

↩︎ - This theme (performed on piano) would show up during the score a few more times, but with the pianist Randy Kerber. ↩︎

- “A Conversation with John Williams”, by Tony Thomas, The Cue Sheet, Vol. 8, Nº. 1, March 1991 ↩︎