In the current Hollywood landscape, it’s a quite established practice to celebrate films’ anniversaries pretty much every five years. Marketing considerations aside, this gives an opportunity (or perhaps an excuse) to revisit on aspects of filmmaking that sometimes get lost in the process of talking about movie “factoids” or celebrating mere nostalgia. Looking back at the music scores is certainly an exercise worth of time.

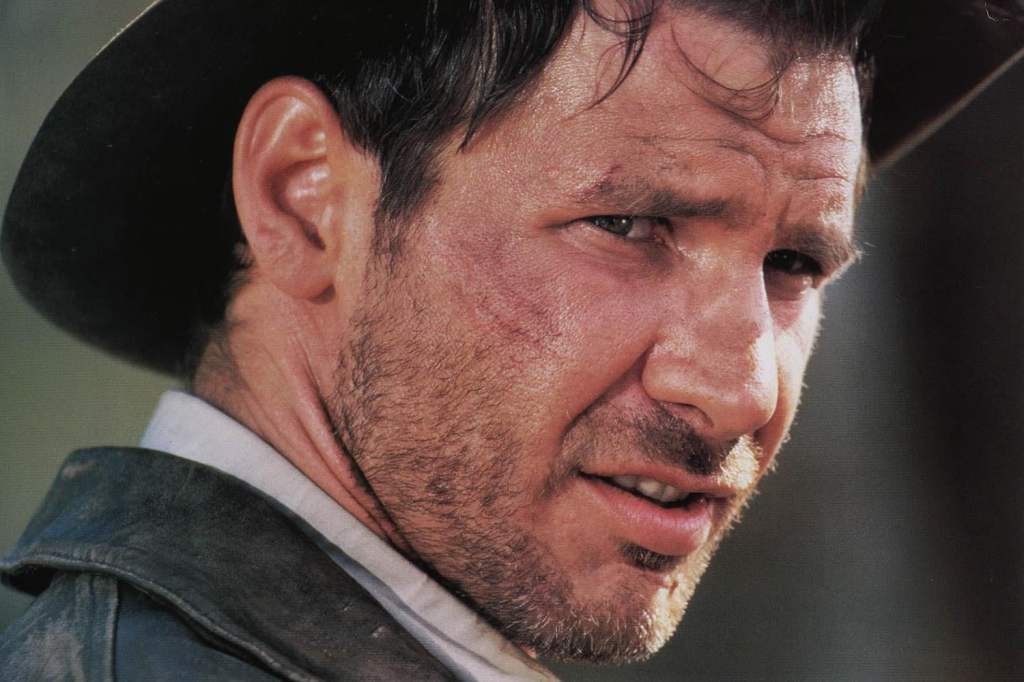

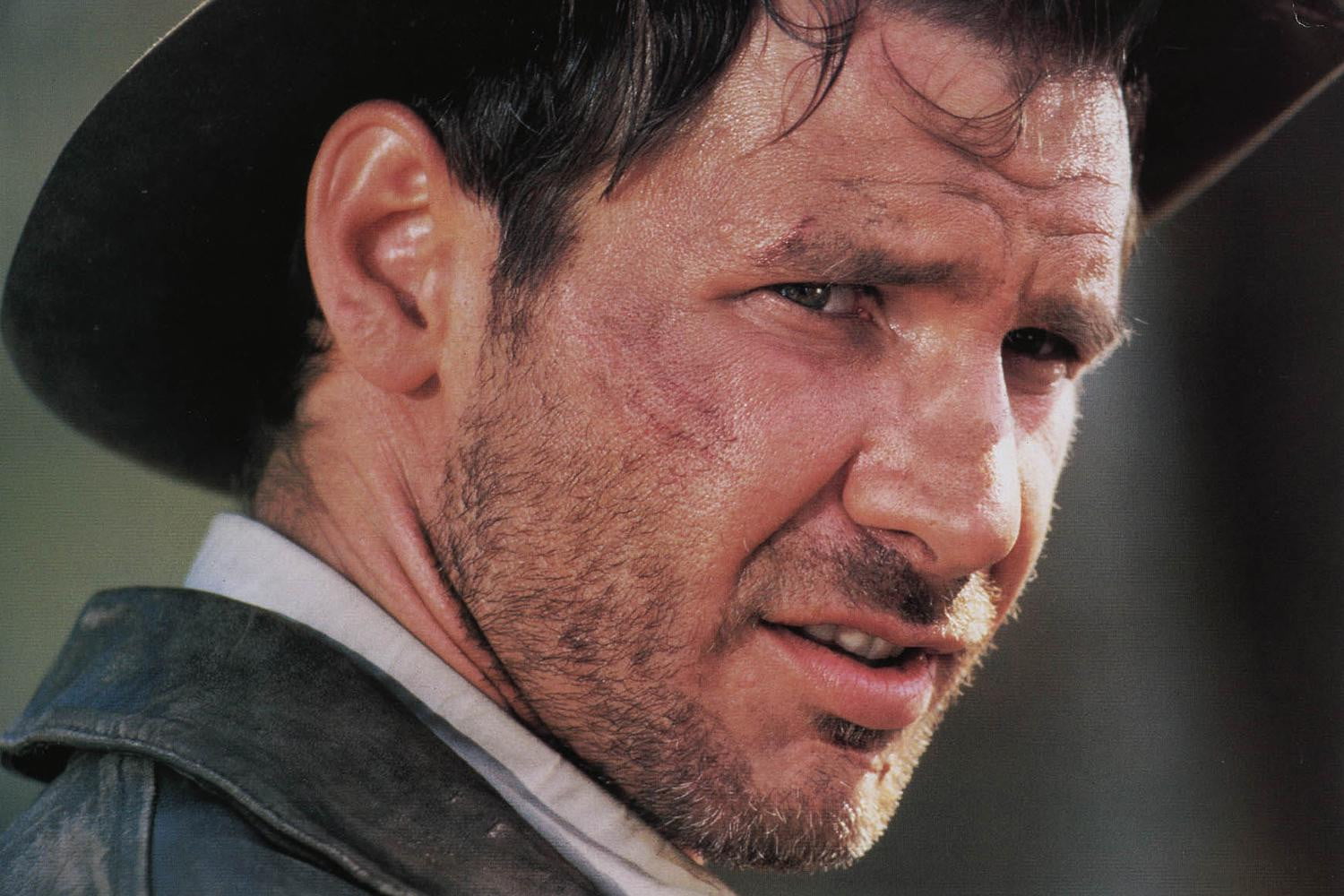

On May 23, 1984, after months of high expectations, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom opens in theaters across the United States to present the second installment of the adventures of the unlikely but incredibly charismatic archaeologist Indiana Jones. In 1981, Raiders of the Lost Ark became the top-grossing film of the year, also garnering eight Academy Awards nominations (including Best Picture and Best Director) and winning five statuettes. It further consolidated the prestige and fame of the two filmmakers who created Indiana Jones: Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. With Raiders, the two movie wunderkinds became the kings of Hollywood’s new blockbuster era they serendipitously started six years earlier with Jaws and continued in 1977 with Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The success of Raiders also turned Harrison Ford into one of Hollywood’s major movie icons and furtherly cemented the need of compelling cinematic entertainment from worldwide audiences. After Raiders, both Spielberg and Lucas turned to other projects, respectively E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) and the then-last episode of the Star Wars saga, Return of the Jedi (1983). Again, both films turned into major box-office champions (E.T. dethroned Lucas’ Star Wars as the most successful film of all time, which took its spot from Spielberg’s Jaws in 1977) and crowned once again the two filmmakers as leaders of the movie industry. But besides the huge numbers and stories of financial success, the creative journey of Spielberg and Lucas epitomizes an idea of cinema and movie-making which remains unique, personal and yet unparalleled. They were able to turn personal dreams and obsessions into grand tales of awe-and-wonder for the world entire, helped by their incredible command of the film-making craft and the talent to create powerful images with state-of-the-art visual effects. However, beyond the technical wizardy, it was the music by composer John Williams that transformed these fantastical adventure stories into tales of timeless wonder.

The second installment of the adventures of Indiana Jones arrived three years after Raiders of the Lost Ark. Both Spielberg and Lucas were keen to return to their character, but this time decided to give a slightly darker edge to his adventures. As Lucas did in The Empire Strikes Back, the second chapter of the hero’s adventure explores the motif of the “descent into hell” found in mythologies, which is represented almost literally in Temple of Doom. The mystical underpinnings found in Raiders give way to dark, sometimes even lugubrious tones that bring the film closer to the thriller and horror genres, thus giving Temple of Doom a quite different atmosphere than Raiders. The spirit at its core remains however the same—it’s still a story spunned from Spielberg’s and Lucas’ love for 1940s/40s adventure movie serials and films like Gunga Din (1939, directed by George Stevens, referenced almost literally in several scenes), therefore the shift in tone is likely consequence of the filmmakers’ desire to avoid repeating a winning formula, but instead surprise the audience with something new and unexpected.

The “MacGuffin” (i.e. the narrative trigger that sets the story in motion, in this case the sacred stones of Shankara) is undoubtedly less compelling than the one used in the previous film, as the mythology that surrounds the artifact is rather nebulous. Temple of Doom retains the comedic tones of Raiders, accentuating even more the cartoon-y situations, to the point that sometimes the suspension of the disbelief could be seriously put in danger. Indy turns from Hitchcock-like hero to a pure comic-strip character (thanks also to Harrison Ford’s more easygoing, light-hearted interpretation), accompanied by sidekicks often reduced to two-dimensional comic-relief characters. The film wears the “B-Movie” nature on its sleeve even more proudly than Raiders already did, with the two filmmakers focused on creating a true amusement park of a film where, for the small price of a ticket, they guarantee you’ll be swept away by frenzy and pure fun. It doesn’t matter much if characters are reduced to mere figurines (or, it would be better to say, action figures) and if narrative coherence sometimes becomes optional; Spielberg and Lucas make the audience thrill and chill at rollercoaster-like speed, in spite of any kind of artistic and intellectual claim. But all this wouldn’t be possible to achieve without the support and enhancement of John Williams‘ dazzling score.

For Raiders of the Lost Ark, John Williams wrote what is unanimously considered one of his greatest film scores. The music accompanies and enhances the amazing adventures of Indiana Jones with excitement, grandeur and a dash of sincere irony, as to remind the audience not to take too seriously what they’re seeing, but absolutely making them believe in it. The theme associated to Indy is one of the Maestro’s most famous pieces of music and one of the most iconic film themes ever written. The “Raiders March”, as it’s called on the original soundtrack album, is the faithful musical translation of the hero. Much has been said and written about this theme, but perhaps it’s worth to revisit and look closer at its musical construction. It’s a simple diatonic tune, but it shifts and moves unexpectedly. As film-music scholar Emilio Audissino wrote in his excellent book John Williams’s Film Music: Jaws, Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark and the Return of Classical Hollywood Music Style (Wisconsin University Press, 2014), the theme is definitely much more cleverly shaped and developed than it would seem at first glance: “From a harmonic point of view, it is built on the simple alternation of I and V degrees—tonic and dominant. It features such Williams idiomatic traits as the added fourth and the omitted leading tone coloring the harmonic pattern, which has a twist in the eighth bar with a chord built in the flattened second degree […] As for the melodic component, it is clear that a good leitmotiv is one capable of revealing musically many traits of the character. […] Another comparison can be made with Luke’s theme from Star Wars. The theme opens with the perfect-fifth upward leap played by trumpets—another Williams idiomatic traits typically employed to depict heroism, as in Superman. […] In the Indiana Jones theme, the heroic traits are also present, but their nature is more uncertain and ironic, and the overall tone is a little more braggart.”

John Williams himself told about how these apparently simple tunes are the most difficult ones to crack:

My first task on Raiders Of The Lost Ark was to create a recognizable theme for the Indiana Jones character. Every time Harrison jumps on the horse or does something heroic, I wanted to pay reference to this theme. I remember playing Steven a couple of options on the piano. He loved them and simply said, “Why don’t you use both?” So those two tunes became the main theme and bridge of what we know call The Raiders March. The interesting thing about The Raiders March is that it is a very simple little tune, but I spend more time on those bits of musical grammar than anything else. The sequence of notes has to sound just right so it seems inevitable, like it has always been with us. It was something that I chiseled away at for a few weeks, changing a note here and there, to find the correct musical shape. Those little simplicities are often the hardest things to capture.

But there is more than the “Raiders March” in this score. As the film is a deliberate and affectionate homage to those adventure films and serials of the 1930s and ’40s, John Williams’ music pays tribute to the style and approach of the great film scores by Max Steiner like The Treasure of Sierra Madre, including the opportunity to write a fully fledged old-fashioned love theme for the heroine Marion and dark, brooding music for the evil guys, but always keeping the tongue firmly in cheek. The composer himself told:

I used to love the romantic themes in those old Warner Bros. love stories like Now, Voyager, the kind of melodic sweep we would occasionally get from composers like Max Steiner. In Raiders Of The Lost Ark, for the love story between Indiana Jones and Marion Ravenwood, I thought an emotionally larger-than-life theme would contrast well with the humour and lightness in the way Harrison Ford and Karen Allen played their scenes together. Even if we didn’t have the obvious, traditional love scenes, I felt it was permissible to inject that musical emotion into their relationship. What I loved – and still love – about the Indiana Jones movies is that they do present a wide range of musical challenges. We go to great lengths to frighten the audience and sometimes use advanced orchestral techniques, atonal music that would be more akin to contemporary concert music. If people hear the music without seeing the images, they might be shocked by it, but for me, those things are terrific fun to do. I also remember doing pastiches of dark orchestral stabs that would represent the evil Nazis when they got into their tanks, drive their cars, issued their orders. The orchestra hits these 1940s dramatic chords, the seventh degree on the scale of the bottom, which is like an old signal of militaristic evil. We just did it for the camp fun of it, and it seems that’s admissible in the style of a film like Raiders.

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom continues on the same style and vernacular used in Raiders and Williams turns in a pitch-perfect musical translation of the film. As Spielberg and Lucas reprise the style of the previous film, but adding even more frenzy and excitement, Williams returns to the energetic, swashbuckling symphonic language of Raiders, but augmented by a more feverish, rambunctious approach. Spielberg and Lucas ask Williams to accompany the film from the first frame to the last (there are very few moments of the film in which the score doesn’t play) and emphasize what happens on the screen to the nth degree—the music accentuates everything we see on screen, from the most insignificant event to the most spectacular and preponderant one. Williams writes a tumultuous, explosive score, a true musical firework like nothing he had ever written before. The composer stretch the ballet-like character of the score to its most extreme possibilities, making the orchestra literally running and dancing for the whole duration of the film. It’s almost a boisterous score, but nevertheless light-hearted and cartoon-ish. The composer knows well the nature of the film and therefore he cannot take himself too seriously. It’s a splendid example of “symphonic cartooning”, in which the music frequently goes into the so-called mickey mousing territory, but always keeping its integrity and reaching levels of incredible virtuosity.

The most perfect encapsulation of this approach is the opening title sequence. As in Raiders of the Lost Ark, the prologue is almost a movie in itself, but before taking us in the midst of action, Spielberg and Lucas pull back the curtain with an unexpected and apparently incongruous musical number—the film opens with the female protagonist, American singer Willie Scott (portrayed by the future Ms. Spielberg, Kate Capshaw) performing a Mandarin-translated version of Cole Porter‘s classic tune “Anything Goes”. The choice is puzzling only on its surface, but reveals the profound awareness of the filmmakers (including their composer), as if they are saying to the audience: get ready, you’re in a adventure movie that opens with a musical and literally anything can happen—but, hey, let’s not take it too seriously. It’s also a marvelous showpiece of Spielberg’s longtime fascination with the musical genre, executed in perfect Busby Berkeley-like style. Williams’ luxuriant arrangement of Porter’s tune is also a delightful tribute to the great orchestrations of classic MGM musicals by Conrad Salinger.

Temple Of Doom had a darker coloration but always with a sense of tongue-in-cheek. One of my fondest memories of all the movies is Kate Capshaw singing Anything Goes in Mandarin Chinese. I love Cole Porter and I got the biggest kick out of doing that pastiche, with a female chorus and antique sax. It was a great send-up of early 1930s Hollywood musicals.

The score of Temple of Doom is rich with thematic ideas, orchestral colors and myriads of big and small musical inventions. John Williams uses the film as a canvas on which he can splash an impressive array of colors, enhancing the exotic tones of the story while heightening the excitement of the adventure. The main new thematic idea written for the film is a great example: a victory parade in minor mode composed as the liberation march for the slave children imprisoned in the mines by the Thugs. It’s a forceful, driving composition that recalls the traits of epic Miklòs Ròsza’s scores and reaches a great climax in the sequence where Indy saves the children and returns them to freedom.

As he frequently does, Williams avoids giving too rigid constraints to themes (especially those not related to a specific character), but instead uses them in their value of emotional catalysts for the audience. The slave children’s theme is used also as a leitmotif for the positive power of the Shankara stones, as we can hear when the starving village’s shaman blesses the departure of our heroes to the city of Pankot, or in the final duel between Indy and Mola Ram, when the power of the stones defeats the evil priest (at 2:44 in the piece below):

The theme for Short Round (Indy’s little Asian sidekick) is another example of Williams’ ability in constructing themes and interrelating them with the rest of the musical materials. It’s a jolly pentatonic melody that vaguely evokes the styles of oriental music and acts as a youthful counterpart to the adult masculinity of Indy’s theme, but also able to play in perfect counterpoint with it (as can be heard in the end credits suite). The theme accompanies the heroic feats of the young kid, but the most radiant rendition appears during the elephant trek sequences, where this simple melody is enriched by a luxurious symphonic treatment (it’s also one of Steven Spielberg’s own favourite John Williams pieces).

Williams addresses also the romantic side of the story, this time between Indiana Jones and the singer-turned-adventurer Willie Scott. It’s a lovely lyrical theme, frequently exposed by oboe or flute in the more intimate settings. It follows the same pattern of Marion’s theme from Raiders, but with much more exaggerated phrasing to underpin the comedic aspect of the romantic relationship. Williams accompanies the bickering between the two characters with playful Tchaikovsky-like pizzicato music, as to reinforce the cartoon-ish element of the love story as well.

The music for the villains is probably the most original and surprising thematic material. The “Temple of Doom” sequence is a gloomy, almost lugubrious composition for male choir and percussion set to a Sanskrit text (a language that Williams will use also for the text of the choral piece “Duel of the Fates” for Star Wars Episode I – The Phantom Menace in 1999). The composition accompanies the sequences of the macabre Thug ritual, becoming by association the theme for the evil Mola Ram. The piece was written before the film started shooting (it was used on set during filming of the temple sequences) and it works cleverly both as score and source music.

It’s however in the many action scenes and set-pieces that the composer shows the uncanny dexterity of his writing, but also his ability to sustain and reinforce the events unraveling on the screen. The music is virtuosic, full of sudden key changes, frequently set at very quick tempo, orchestrated for a very large orchestra augmented in brass, woodwinds and percussion, reaching points of feverish excitement. It almost sounds like music for a manic cartoon, like Wile E. Coyote chasing the Road Runner, but never to the point of sounding like a parody of itself. Quite the contrary, Williams is very careful to balance the comedy tones with dramatic and theatrical gestures to enhance Indy’s heroics. Talking about scoring action sequence in films like Indiana Jones, the Maestro explains his meticolous methodology:

I always approach those things particularly with Steven in sort of balletic terms. I look at it as a kind of musical number that has a beginning, a middle and an end, and try to calculate a series of tempos, and a series of changing tempos. I will try to design it almost in the same way as you would a balletic number, which may contribute a certain aspect of fun and adventurousness in this Harrison Ford character. The music may sound serious but it’s not really, it’s more theatrically conceived and hopefully always has an aspect of fun or even camp about it.

Perhaps the score’s utmost example of this approach brought to its most extreme consequence is the music that accompanies the chase of the mine cars. The dazzling sequence looks very much like a declaration of the film’s Spielberg-ian intertextual motif of “movies as an amusement park”. The scene is scored by John Williams with a piece of absolute virtuosity, with piccolos and xylophones literally running at high-octane speed. This brilliant composition reveals also a surprising connection to John Williams’ own family. The piece contains a slight nod to “Powerhouse”, a 1937 jazz composition by the great American jazz group Raymond Scott Quintette (in which John Williams’ father played drums). This composition was acquired by Warner Bros. in 1943 and used frequently in scores for cartoons produced by the studio, arranged and adapted by Carl Stalling. Williams here nods to his father’s musical heritage, to his love for 1930s jazz and to the scores of cartoons by Warner Bros., coalescing it all into his own unique musical personality.

John Williams’ score for Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom is an enthralling and genuinely exciting example of the composer’s unrivaled talent to support and enhance storytelling, action, drama and comedy. The final recapitulation of all themes in the finale and end credits sequence then sounds as a joyous celebration that enhances the same feeling of exhilaration and fun we have when we walk out from an amusement park… or a movie theater.

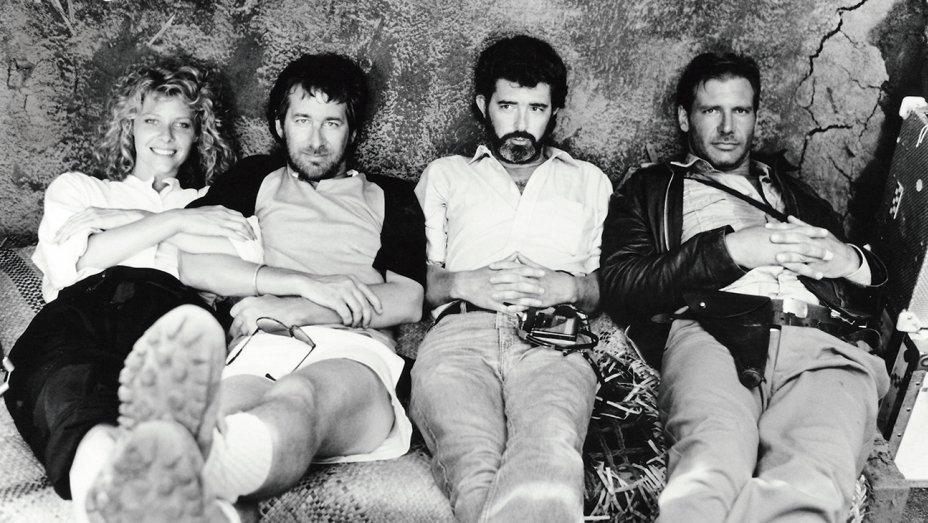

For John Williams himself, working on these films has been above all a real excuse to have fun with his two collaborators Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, with whom he shared a great deal of “fortune and glory”.

Working with these two gentleman is always a joyous experience. We get along as people so well, we have the same sensibilities and tastes about scenes, and when we hit upon something that works, we all seem to agree about it. That’s another way of being in sync. On all four films, it has been filmmaking that is more play than work.

Like the films themselves, the music of John Williams for the Indiana Jones series give us the extraordinary excuse to have fun and remember the kid in ourselves a little bit. It’s larger-than-life music for a larger-than-life movie hero.

Quotes of John Williams interviews taken from:

Indiana Jones and Me: John Williams, Empire Online, October 2012 https://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/indiana-jones-john-williams/

Raiders of the Lost Ark – Original Soundtrack Album (1995, DCC Classics) – Liner notes by Lukas Kendall