Ehnes and Denéve on Bernstein and Williams

Using two successful composers for only one recording program has been a marketing ploy for almost as long as records exist. The present release from Pentatone Records featuring works by Leonard Bernstein and John Williams performed by James Ehnes and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra conducted by Stéphane Denève can be taken as a great example of how this can be achieved to everyone’s benefit. It can be used to the advantage of the performing artists, allowing them to present works by composers they admire even though these composers might not please (at least at first sight) the same kind of audience so that fan bases can be shared. Said marketing ploy also allows for companies to reach a wider public, and it allows us, the listeners, to eventually discover new works and new composers.

Leonard Bernstein has long been a prime example of American music compilations. When not dedicating an album uniquely to his own work, it has been customary to find him sharing composing credits with Aaron Copland (his composing mentor and lifelong friend), Samuel Barber or George Gershwin, to name a few composers who achieved great popular and critical success, and of whom Bernstein was also a champion. This mixing of composers did not only happen with later re-releases but upon the release of the original concept album as well.

Earlier examples of the coupling of works by different composers, featuring Leonard Bernstein, the composer, pianist and conductor

What we have just described holds also true for the present release of Bernstein’s and Williams’ Violin Concertos: Both composers have reached a status that makes them giants in the American musical scene, both achieving great popular success on more accessible venues (Bernstein on Broadway, Williams at Hollywood) while striving to gain critical recognition with “serious” concert music. As for Leonard Bernstein, this recognition was almost inevitable. Not only because of his mentors Aaron Copland and Serge Koussevitzky (the long-standing Russian music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and founder of what is now the Tanglewood Music Center) but certainly due to his highly visible concert career, both as music director of the New York Philharmonic and guest-conductor of some of the most important orchestras in the world. Nevertheless, Bernstein always struggled to get his music out of his system, and while the musicals were fun collaborations that seem to have always been a natural extension of his extroverted self, secluding himself to write a symphony or an opera was a difficult affair. Bernstein was a well-known attention-seeker after all, and composing kept him painfully away from the spotlight. His frustration with that side of his career can’t be more apparent than on his quest to write the “Great American Opera,” his final attempt being A Quiet Place, which met with mixed reviews at the time of its premiere. (One might argue he had already achieved his “opera” goal, just not at the opera house, with the seminal West Side Story. But alas, they called it only a musical…).

Both composers had just experienced great success ahead of writing their pieces for violin: Bernstein with the successful musical Wonderful Town, Williams with high profile film projects that led to numerous nominations and awards, including his first Oscar for Fiddler on the Roof.

John Williams’ career can be regarded has having some parallels. Also born a natural musician (in Williams’ case as the son to an accomplished percussionist, while Bernstein had a later start when a piano was dropped at his house), he followed a composing career after realizing that a career as a concert pianist wasn’t likely to happen. He was still a good enough pianist to be much in demand at the Hollywood recording studios, and in 1961 he became the session pianist for the film version of West Side Story. With a much more introverted demeanor, being kept away from the limelight while composing didn’t bother Williams and so he has amassed an amazingly long list of credits ever since. And even though he has enjoyed a more visible concert career since the late 70’s, his output remained always regular, both in quantity and quality. While Williams has often spoken of his concert hall compositions as some sort of experimentation, no one creates a body of work that large unless one looks, even unconsciously, for acceptance within the rather restricted and hyper-selective world of the concert hall.

Further parallels can be drawn between the two artists. Both Leonard Bernstein and John Williams adapted their most famous and accomplished compositions for a “proper” presentation at the concert hall, creating sometimes multiple suites from their ballets, musicals and film scores (and in the process, helping to introduce those idioms into the sacrosanct concert hall). And both forged close and long-lasting performing relationships with the musicians for whom they even wrote original music later on. Both composed a wealth of works that, even if some were not well-received at first, have stood the test of time. And in incorporating popular idioms into their own writing, they made their music clearly American and went against the post-war current of Darmstadt and the second Viennese School. (But in all fairness, both composers have also included elements of this trend, thus creating their personal idioms while adding to the melting pot, efforts which made them at the same time unique and highly recognizable).

And another parallel: Both composers have written violin concertos at pivotal moments of their lives, and both concertos are about love.

Leonard and wife Felicia Bernstein with close friend composer David Diamond, around the time he was writing Serenade (Pisa, Italy, March 1954) – Photo Credit: Library of Congress Music Division

Leonard Bernstein’s Serenade (After Plato’s Symposium) isn’t called a violin concerto, even though one can see it as such a piece of music [1]. It was written at a point when Bernstein was experiencing his first string of success on all fronts. Wonderful Town had just become a Broadway hit, and regular conducting engagements in the United States and Europe added to his fame, while West Side Story and the appointment as Music Director of the New York Philharmonic were only a few years away. Even though his personal life was filled with turmoil, this was a period of bliss. He spent the Summer of 1954 in Europe with his wife Felicia Montealegre and their first daughter Jamie while focusing on composing what ended up being the Serenade. (The Bernsteins had married just three years earlier, after an odd and long engagement, filled with interruptions and gossip, so the composer was now ripe for accepting the joys of being a family man). As the story goes, the motivation for the Serenade was a re-reading of Plato’s Symposium, a collection of dialogues where the central theme is love in all its manifestations and variations. The work was a commission from the Koussevitzky Foundation, and although presented after some delays, Bernstein was allowed to premiere it in Venice, Italy with his beloved Israel Philharmonic and Isaac Stern as soloist. Composed for solo violin, strings, harp and percussion, it is structured in five movements, each one built over melodic material from the previous one, with occasional references to other ideas already heard before, thus creating an interconnection between the whole structure. The piece opens with a lyrical cadenza that sets the tone for the subject matter, even though Bernstein never provided a proper programmatic guide to the piece, stating that “the music, like the dialogue, is a series of related statements in praise of love and generally follows the Platonic form through the succession of speakers at the banquet.” (Actually, at the time of the premiere, detractors would point out that the Serenade had no influence whatsoever from the texts it was said to have been inspired by, a judgement based on Bernstein’s regular reappropriation of shelved material from unmaterialized projects – and on occasion from projects that lacked popular success and still had promising material that the composer wanted to be heard).

After the introduction that reflects Phaedrus and his speech in praise of God Eros, the music builds up with a bouncier dance-like melody (that would have been a perfect fit in any of the composer’s musicals) while describing in musical terms a speech about the duality of lover and beloved. The second movement is in a slower tempo, marked “allegretto”, and explores the fairytale world of love, reworking some of the material from the first movement in an appropriately dream-like fashion. The central movement is a mercurial fast scherzo, using material from the central section of the previous movement and demanding stamina from the soloist, as one addresses matters of a more physical dimension. Agaton’s speech, represented in the fourth movement, returns to a slower tempo (“adagio”), because the speech embraces all of love’s aspects. This music is akin to attending a rather serious lecture, much sterner and with a long introspective cadenza, beautifully interrupted by the strings with the return to material from the Serenade’s opening cadenza. In the humble opinion of this writer, this is certainly one of the most beautiful moments of the piece. While the finale starts on a somewhat similar serious note as certain parts of the previous movement (developing on material from it) with a vigorous introduction of the strings and percussion, followed by a dialogue between soloist and cello in duo cadenza fashion, the music eventually evolves with the integration of some jazzier elements and the return of the main material of the other four movements, concluding in an exhilarating manner with the opening theme.

Leonard Bernstein and Isaac Stern in Venice, September 1954. Photo Credit: Library of Congress Music Division

Ehnes, Denève and orchestra present a lively account of the Serenade. While I have collected a few recordings of this piece, including the first one with Isaac Stern under Bernstein and the Symphony of the Air, recorded shortly after the premiere, I tend to return more often to the composer’s 1979 recording with Gidon Kremer and the Israel Philharmonic. Where Bernstein and the Israel Philharmonic tend to have a rougher edge, dully followed by the soloist, I feel Ehnes and Denève decided on a softer toned path. Nevertheless, both renditions of the piece (despite the authority of the former having the composer conducting) offer a crystal-clear presentation of the music and all its subtleties, allowing to acknowledge what was the inspiration for the composition. (Which, despite the aforementioned detractors, makes quite a lot of sense.) In the booklet, Ehnes relates how he feels this piece “represents the most successful musical marriage of his (the composer’s) various artistic personalities. It is a work of great profundity, but also of the most raucous merriment!” The soloist shows quite a lot of understanding in his performance, properly balancing the vast vocabulary of Bernstein’s own musical language and providing that “successful marriage” in the form of this beautiful ode to love with its many aspects.

John Williams and his late wife Barbara Ruick, at the L.A. premiere of Goodbye Mr. Chips (1968), for which he was nominated for an Academy Award

Like Bernstein, John Williams was going through an early stretch of artistic success in 1974. Having already had several pieces commissioned and premiered by the likes of Stan Kenton, André Previn and the Houston Symphony and Donald Hunsberger and the Eastman Wind Ensemble, Williams was en route to becoming the household name we are now used to (not unlike what happened with Bernstein). In the late 60’s he had already earned serious recognition with one Emmy Award for the 1968 television film Heidi and several nominations for Academy Awards, receiving his first one in 1972 for his work on Fiddler on the Roof (where he worked with violinist Isaac Stern, arranging some brilliant cadenzas based on Jerry Bock’s material) and had already forged a number of important connections with producers and directors. His relationship with Steven Spielberg, started in 1973, becoming pivotal in his film music career and remains active to this day. Jaws, their second collaboration, was just around the corner and would earn the composer many accolades, including his first Oscar for Original Score. Another collaboration that dates back to the early 60’s (when Williams was still working for weekly television shows) was with director Robert Altman, with whom he had recently collaborated back-to-back on two feature films, Images (for which Williams got an Academy Award nomination) and The Long Goodbye. The families of both Williams and Altman were close, sometimes sharing family dinners, and Williams would even score some home movies of his director friend. Also, as with Bernstein, family events occurred that would mark John Williams’ output, but unlike in the life of the elder composer, the most striking one was rather tragic than blissful. On March 3, 1974, while filming on location in Reno, Nevada, for Altman’s upcoming film California Split, Barbara Ruick Williams died suddenly, leaving the soft-spoken and somewhat introverted composer devastated. It has been told that this made him even more removed from public life and protective of his privacy. Unlike Bernstein, who was always fond of the spotlight, Williams provides little information on how he used his first Violin Concerto to deal with his emotional catharsis – apart from some technical chatter. We are simply told that the concerto was suggested by Ruick and it is dedicated to her memory. Work on it began shortly after her passing and was concluded in 1976 [2]. It remained on the composer’s shelves until Leonard Slatkin, a champion of Williams’ music (Slatkin’s parents were Los Angeles based musicians who would also play on studio sessions, knowing Williams from those), picked it up and premiered it with the Saint Louis Symphony and violinist Mark Peskanov in 1981. A recording with Peskanov accompanied by the London Symphony conducted by Slatkin followed a couple of years later, with the composer in attendance.

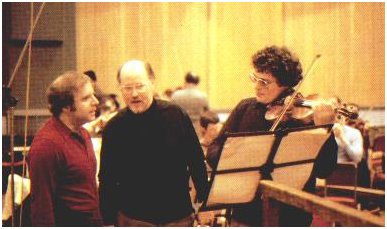

Leonard Slatkin, John Williams, Mark Peskanov, during the recording of Williams’ Violin Concerto at Abbey Road Studios in London, December 1981

While Bernstein’s Serenade is made up of a collection of musings on the subject of love, which even ends with the same melody it started, the Williams’ Concerto is more akin to a journey where one is driven by the loss of love – the prevailing tone of the piece being a sombre, bittersweet one. The lyricism in the thematic material is still there but seems unresolved sometimes, almost as if the composer was in search of something that had been lost forever. Even though Williams has remained protective of his feelings and inner motivations and shared only some technical remarks, they help to understand the elegiacal and mournful nature of the piece right from the start. The first movement, marked “Moderato”, opens with a violin cadenza, but while in Bernstein’s Serenade the cadenza is filled with delightful lyricism about enchanted people in love, Williams’ cadenza starts off with a mournful tone right away. A lower strings pedal note adds gravitas (an addition in the 1998 revision of the score) although it’s almost silent on the present recording. The violin soliloquies move on, adding some exclamations before the flute and then the full strings join in that same main melody. Further development follows until we reach a tutti that sounds like an interruption out of despair. Notwithstanding, the violin continues to develop on the main theme idea, always accompanied by the orchestra and by occasional returns of its earlier partner, the flute, until a new and bouncier theme is presented almost midway through the movement. This contrasting material has an almost devilish quality even though it continues to share the DNA of the opening thematic idea that keeps trying to return. Woodwinds (again with a particular focus on the flute) offer support to these explorations until we reach a long and stern cadenza for the soloist. Eventually the woodwinds interrupt it and allow the soloist some rest until the strings come back and the soloist quickly recapitulates thematic material presented throughout the movement, quietly concluding it. The second movement is marked “Slowly”, suffixed with “In peaceful contemplation”, and there couldn’t be a more adequate description to this beautiful elegy for violin and orchestra [3]. I believe it was Denève himself who referred to this movement as close to Williams’ film work. While I’m not fond of that kind of comparison, the cantabile nature of what the conductor calls an “elegiac and nocturnal melody” that seems “to express a devastatingly perplexed solitude” may help to make that sort of connection. Moreover, the composer himself referred to the Concerto being “atonal in style and technique” but still “lying within the romantic tradition”. And that certainly becomes rather obvious, not only in the overall traditional architecture of the Concerto (three movements, fast with cadenza – slow – fast), but even more so in its middle movement. The opening material is set under a bed of strings playing a rocking rhythm while the violin sings a beautiful yet melancholic berceuse. Eventually the orchestra joins the violin in a more active way, either in contrast or support (there’s a wonderful short duet near the end of the first section of the movement). A faster musical idea comes next, soloist and woodwinds rambling away with it, before strings return in full strength with some help of brass and percussion to bring it to a dramatic climax. Then soloist, woodwinds and strings return to the faster idea for further development before revisiting the opening theme which closes the movement with a slightly less mournful tone. The final movement “Broadly – maestoso” starts with exclamations of the orchestra, interrupted by virtuosic passages on the violin that almost suggest, from a kinetic standpoint, that it is trying to escape – first from the full orchestra and then from the woodwinds that try to keep up with the soloist. Eventually the whole orchestra makes further appearances providing some needed solace for the protagonist. Material lifted from or based on the previous movements shows up during the violin “walk” through the soft orchestral backing, eventually returning to the main theme of the first movement, playing variations over it, with the help of the loyal flute and horn, when, just as in the end of the second movement, a more hopeful tone seems to surface. It’s a well-known fact that composer John Williams is a lover of nature and trees and in my mind, this magical passage is a perfect representation of walking through a forest in complete (physical, but also emotional) loneliness. The orchestra returns with fast and explosive intrusions, almost trying to save the soloist from some sort of lethargic state of mind, and while blasting the main first movement theme it gives the soloist the chance to permutate it into the most beautiful love song, thus finding solace in memories of lost love. As beautiful as it may be, there nevertheless is some bitter sweetness to it as love is still lost to death even though memories linger on. The jaunty orchestra returns on a lighter note, the soloist joining in a less mournful tone, and together they bring this journey through loss and overcoming to a close.

James Ehnes, John Williams and Stéphane Denève at Powell Hall, St. Louis, November 2019

Stéphane Denève has long been a strong advocate of Williams’ music for film and concert hall alike, and has conducted the Violin Concerto several times with soloists Gil Shaham and James Ehnes, employing numerous orchestras, including the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Boston, St. Louis and New World Symphony Orchestras. The present recording springs from a series of performances in November 2019 by the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra that were coached by the composer himself. It’s interesting to note that the world premiere in 1981 with soloist Mark Peskanov and conductor Leonard Slatkin was performed by the same orchestra, also with the composer assisting in the preparation. The present release marks the fourth commercial recording of the Concerto [4], which makes it second only to the Tuba Concerto in terms of the number of recordings a Williams concert work has enjoyed and equal to the Trumpet Concerto. But how does this new recording compare with the previous ones?

Among the film music community there’s a tendency to always go for the original version of a cue as if it is more valid than subsequent readings which might be free from the time constraints of the movie soundtrack (either dictated by the inner rhythms of the film itself or the tight rehearsal and recording schedules). Even though the CD at hand isn’t a recording of music that was written for film, I can understand how a large section of the target public will look at the original 1981 recording as a main reference. Others will probably put all their sympathy on the 1999 recording (released in 2001) with Gil Shaham and the Boston Symphony that Williams himself conducted, lending it the undeniable authority of the composer being the conductor. But regardless of personal favourites, this new release features a stellar performance by everybody involved. The soloist very clearly encapsulates all the different moods that surface while we accompany the composer’s journey of surviving an unbearable loss. Ehnes and company are able to maintain the needed tension throughout the duration of the concerto, allowing the listener to feel the uneasiness of the violin’s main character. All that stress is released at the absolute right moment, bringing the finale of the Concerto to a glorious and hopeful conclusion even though there can never be a happy ending to it. It’s only speculation, of course, but we may wonder if, when Williams finished the work, his mourning had reached its end yet [5].

The orchestral climaxes are brilliantly executed and Denève handles the orchestral subtleties in such a way that one can hear every little detail. As with the Bernstein Serenade, the St. Louis musicians and their conductor are able to support the soloist without ever overshadowing him. It should also be pointed out that this performance sounds like none of the previous ones. Williams is known to tweak his pieces every now and then. Some of his concert pieces remain unpublished, even if available for performance on special request, because he is not fully satisfied [6]. I don’t find it surprising that some of the alterations were made on the spot as Williams was present for the rehearsal, performance and recording. Maybe he decided on some of them just because of the way the acoustics of Powell Hall worked, on others because he keeps trying to improve what he wrote over 40 years ago. In the end, it’s only natural that two given performances of the same work will sound differently but equally satisfying, and I feel that this happened here with this first release of Stéphane Denève as Music Director of the St. Louis Symphony.

Everything in this release seems to be an act of love. Both Ehnes and Denève talk with great affection for the works recorded, and they both are passionate musicians who share their rare artistry in a rather unselfish manner. (Much like Bernstein, who always enjoyed mingling with fans.) Adding to the beautiful music and the lively sound recording is the packaging, a small jewel of sober design work. Pentatone has found a distinctive way to present their CDs so that you know instantly it’s one of their releases without having to look for the logo. The cover art of this present CD by Marjolein Coenrady shows a beautifully painted starry sky which serves to evoke, with great simplicity, “the memories of beloved ones who have passed, shining a light during our personal phases of darkness and loss” [7].

These two works, by two genius composers who rubbed shoulders in Hollywood, Boston and Tanglewood and who had just as much in common as what set them apart, are a testimony to love in all its facets. They also prove their shared love for music and everything that it allows us to feel and love and live for. In contrast to poetry, which might struggle to fully encompass all that love means (because love is without words), music can talk directly from and to our hearts. After all, it doesn’t know the boundaries of speech and written language. Leonard Bernstein and John Williams have expressed that which cannot be said quite often, but never in such a personal manner as in these works. So have Ehnes and Denève with their passionate and artful performances. And we, the listeners, the final link of the holy trinity made of composer-performer-listener, are the beneficiaries of all this love poured into music. It’s our good fortune to experience it, because “If music be the food of love, play it on”.

A very special thank you to Markus Hable for the invaluable help proofreading and fact checking the different versions of this article.

Footnotes

[†] Paraphrase on Duke Orsino’s first line on Shakespear’s Twelfth Night: “If music be the food of love, play on”

[1] Bernstein’s Symphony No. 2 “The Age of Anxiety” (1947-49), could easily be called the composer’s Piano Concerto, but clearly there was some reluctance in using the word Concerto. The same reasoning applies for his Prelude, Fugue and Riffs (1949), written for legendary jazz-turn-classical clarinetist Bennie Goodman. His later Halil (1981) is subtitled as a Nocturne for Solo Flute and Strings and Percussion but could easily have been called a Flute Concerto. His reworking of The Three Meditations from Mass for cello and orchestra can probably be seen in that same light. Bernstein’s only concession to the word “concerto” came much later in life with the Concerto for Orchestra (1989), after revising and expanding his original piece Jubilee Games (1986), even though it uses more than just an orchestra, calling also for a baritone soloist.

[2] Continuity in both pieces can be seen through the presence of Isaac Stern during the conception of both (and the premiere of the Serenade). Between 1974 and 1976, Williams talked with Stern several times about some of the technical aspects of the work. Stern, of course, was the preeminent violinist in the United States and had recently worked with Williams as soloist for the film version of Fiddler on the Roof. While Stern never performed the Williams’ Concerto, they did perform together again, including at Williams opening concert as Principal Conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra in 1980.

[3] It’s of interest to note that Denève, as a champion of Williams’s music in general and the Violin Concerto in particular, conducted this slow movement as a standalone piece at the Tanglewood on Parade Gala Concert of 2015 with former Boston Symphony Orchestra associate concert master Tamara Smirnova and the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra.

[4] The recordings of Williams’ Violin Concerto No. 1 († indicates revised version of 1998): Peskanov/London Symphony/Slatkin, 1983, Varese Sarabande VSD-5345; †Shaham/Boston Symphony/Williams, 2001, Deutsche Grammophon 471 326-2; †Boisvert/Detroit Symphony/Slatkin, 2011, Naxos Digital Release Only; †Ehnes/St. Louis Symphony/Denève, 2024, Pentatone PTC 5187 148

[5] One might even go a step further, and wonder if it ever did… In 2013, during an interview with Jim Svejda, when talking about the Violin Concerto and its relation with Barbara Ruick, Williams’ voice was clearly choked up, maybe a sign of someone who still dearly misses his late wife. (John Williams Concert Works Interview, with Jim Svejda, April 25, 2013, Classical KUSC FM 91.5)

[6] His Cello Concerto, written in 1994 for Yo-Yo Ma, has gone through at least three major revisions, while the Trumpet Concerto, written in 1996 for Michal Sachs, has had two revisions. Other pieces have had very minor corrections (that the composer won’t mark as a revised version of the piece) and the Violin Concerto No. 1 seems to be such an example after the more substantial revision of 1998.

[7] Quote by Kasper van Kooten, Pentatone Head of Catalogue (https://tinyurl.com/2zkh8xsu)

WILLIAMS Violin Concerto No. 1/BERNSTEIN Serenade

James Ehnes, violin

St. Louis Symphony Orchestra

Stepháne Denève

Now Available on CD at Pentatone

Also streaming on YouTube and Spotify

References

. Concerto for Violin and Orchestra – Work page at The Legacy of John Williams

. Interview with James Ehnes on John Williams and Leonard Bernstein, Prestomusic.com