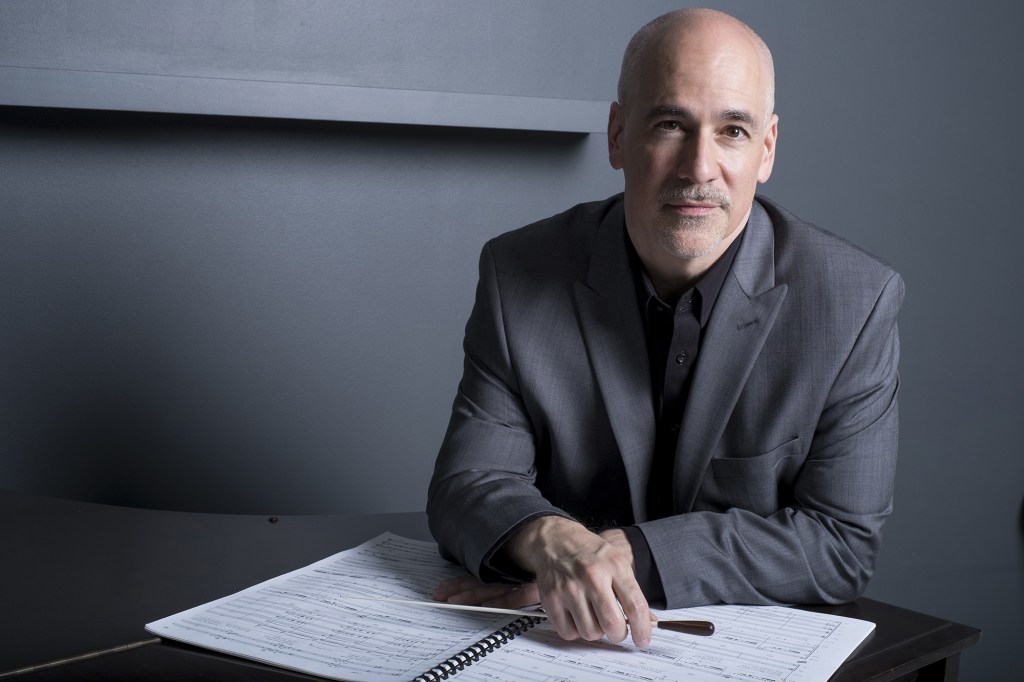

Peter Boyer is one of the most performed American orchestral composers of his generation. His works have received over 500 public performances by more than 150 orchestras, and thousands of broadcasts by classical radio stations around the United States and abroad. He has conducted recordings of his music with three of the world’s finest orchestras: the London Symphony Orchestra, the Philharmonia Orchestra, and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Many of America’s most prominent orchestras have performed Peter’s music, including the Boston Pops, Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Cleveland Orchestra. His music has been recorded by many classical labels and his second recording on Naxos, featuring his Symphony No.1 and four other works with the London Philharmonic under his direction, was released in 2014.

Boyer’s major work Ellis Island: The Dream of America, for actors and orchestra, has become one of the most-performed American orchestral works of the last 15 years, with over 200 performances by more than 90 orchestras since its 2002 premiere. Boyer’s recording of Ellis Island on the Naxos American Classics label was nominated for a GRAMMY Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition. In 2017, Ellis Island was filmed live in concert with Pacific Symphony and a cast of stage and screen actors for PBS’ Great Performances, America’s preeminent performing arts television series.

He has served as Composer-in-Residence of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra (2010-11) and the Pasadena Symphony (2012-13). His most recent commissions include two from the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, and one from “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band, in celebration of its 220th anniversary in 2018.

In addition to his work for the concert hall, Boyer is active in the film and television music industry in Los Angeles as an orchestrator. He has contributed orchestrations to more than 35 feature film scores for leading Hollywood composers including James Newton Howard, Thomas Newman, Michael Giacchino, Mark Isham, Alan Menken, Harry Gregson-Williams, and the late James Horner. Among his film-related work, he also served as assistant/cover conductor for The Lord of the Rings in Concert, in performances in Melbourne, Munich, Seattle, and Barcelona.

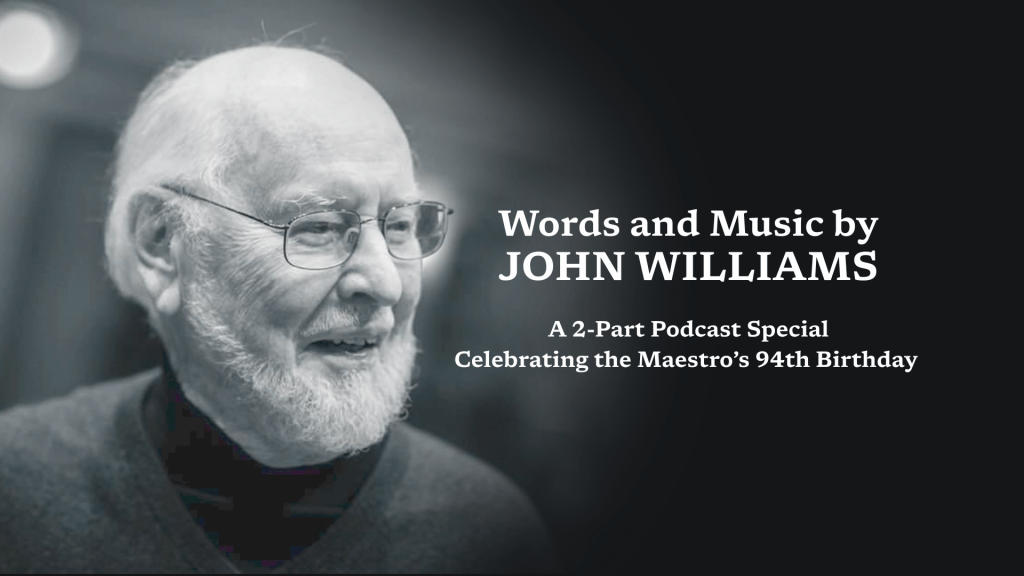

As you can see, even just a quick glance at his resumé shows an impressive and varied array of skills and talents. Above anything else, Peter Boyer is a composer of heartfelt, sincere and uplifting music, replete with colorful orchestrations and a refreshingly tuneful approach, also showing a great deal of knowledge and command of the symphony orchestra. In this sense, he seems to inherit the exuberant and joyous side of one of his heroes’ music: John Williams. In fact, Boyer never hidden his great deal of admiration and reverence toward Williams’s music, acknowledging the composer as one of his role models together with Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein.

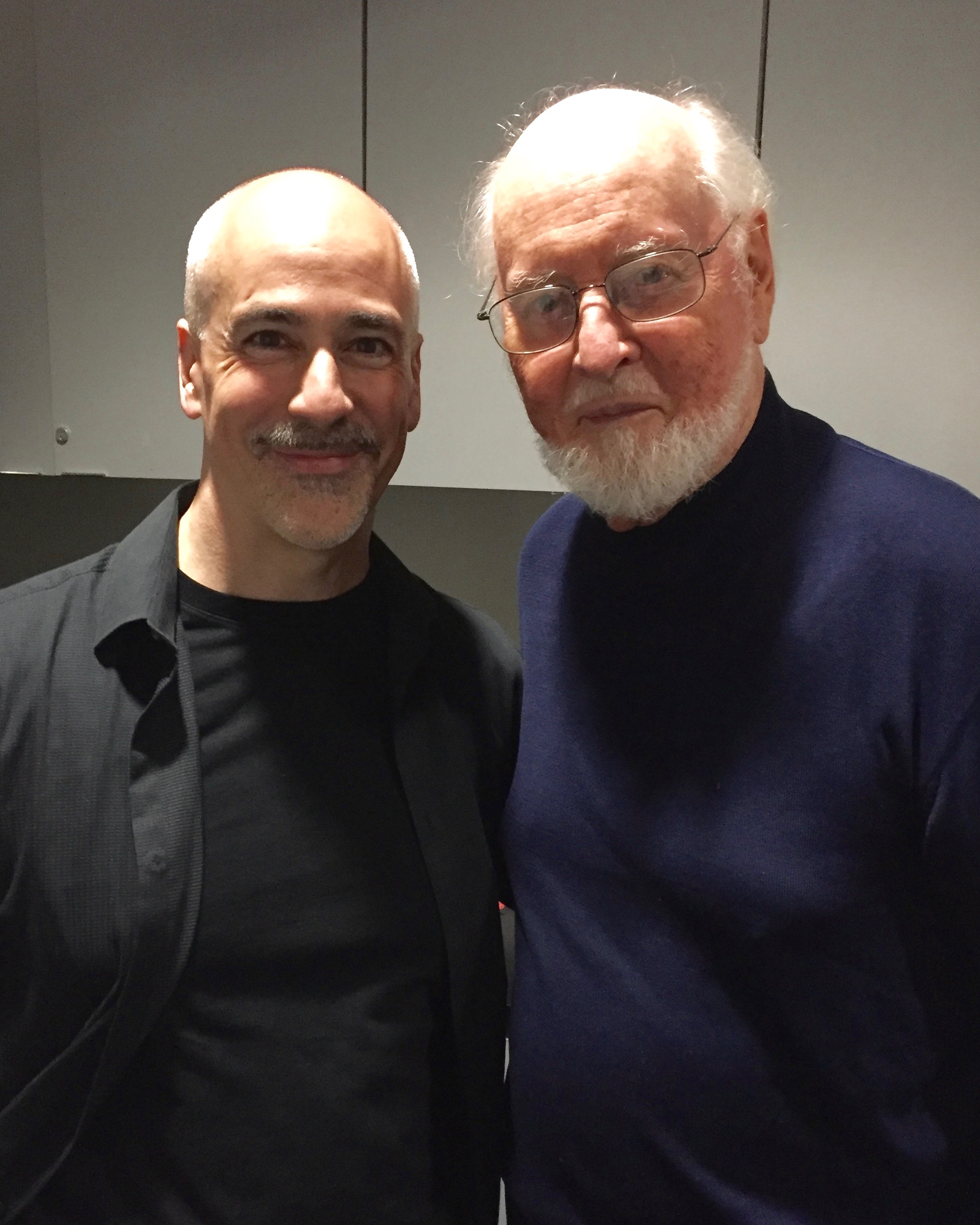

Peter accepted our invitation to talk about his career in classical music, his own approach to composition and how the music of John Williams accompanied and influenced his own artistic journey, while reflecting also upon the great legacy of the composer in the heritage of American orchestral music.

Thank you very much for accepting to talk with The Legacy of John Williams about your music and your career, Peter.

It’s a pleasure to do this interview, and thanks for your interest in my work.

First of all, I want to ask about your musical background and formation. You started composing orchestral music at a young age. How and when did you decide to become a composer? Did you want to establish yourself as a classical composer and write mostly for the concert hall since the beginning of your career? Or was that more of a consequence of your study path?

My childhood did not include serious music study, though I did take some lessons in guitar (pop, not classical) starting around age 10. When I was a teenager, I was a huge fan of several popular American singer-songwriters, such as Billy Joel, Paul Simon, Dan Fogelberg, and others, and pop/rock groups such as Journey and the Eagles. So American popular music was primarily what I listened to, and this became the formative influence in my earliest days as a young musician. When I began playing the piano and composing, at age 15 in high school, it was in this pop music genre; I started as an aspiring singer-songwriter, and gave my first public performances of this sort soon after, in my native Rhode Island. I took to the piano and composing fairly naturally, though I was a late starter, and music became the dominant interest in my life starting then.

When I was in my junior year of high school, just turning 17, a couple events coincided which ended up having a big impact on me. I was taking a music history course, and learning something about classical music and composers for the first time. My paternal grandmother, who had gotten me my first piano and arranged for my first music lessons, died suddenly; and at that same time, I heard the Mozart Requiem for the first time in this music history class. So I got in my head the crazy idea that I would compose a Requiem Mass, and dedicate it to my grandmother’s memory. Not having a composition teacher (I didn’t have formal composition lessons until I went to graduate school), I took scores and recordings of Requiem Masses by various composers out of my local library, starting studying them, and started composing one. It’s a long story, but three years later, when I had just turned 20 and was a junior at Rhode Island College, I conducted the premiere of my 40-minute Requiem with soloists, orchestra, and choir — about 300 performers in total. I had received a great deal of support from teachers, administrators, and community members, without whom I could not have done this; but essentially I was this insanely ambitious teenage composer, and managed to do this, which was my first major piece of concert music. It received a great deal of media attention, including recognition by the national newspaper USA TODAY, and the response in my community was overwhelming. I was just a college student, but this was a formative experience on my path to becoming a composer.

I went on to do graduate studies (M.M. and D.M.A. degrees) at The Hartt School of Music, a conservatory which is part of the University of Hartford. There I studied composition for one year with Robert Carl, and for three years with Larry Alan Smith (who had studied with Vincent Persichetti at Juilliard, and also with Nadia Boulanger). Larry was my principal composition teacher. Additionally, I studied conducting for three years with the late Harold Farberman, one of the better-known American conducting teachers, who was also an accomplished composer. I learned a huge amount during these intense years of study, which were formative times for me.

After I completed my doctorate at Hartt, I studied privately with John Corigliano in New York. This was for just one summer, but even this fairly brief period of work with him made a huge impression on me. Following that period, I relocated to Los Angeles, and completed the one-year program in Scoring for Motion Pictures and Television at the USC (now Thornton) School of Music, which is where I met and studied with the late Elmer Bernstein, among others. I suppose the fact that I did this one-year SMPTV program at USC after having completed a doctoral degree showed that my dual interests in concert music and film music were there even then. But as you suggest, composing for the concert hall certainly has been my primary focus, and I think my passion for that field can be traced all the way back to my formative musical experiences in high school and college.

That’s certainly a fascinating and rich background. Let’s now talk about the subject of this website. Do you remember the first time you encountered the music of John Williams? How much of an impact did it make on you?

Like many others of my generation, I would imagine that the first time that I encountered John Williams’s music was in Star Wars, which came out in 1977, when I was seven years old. I doubt that I would have had awareness of who Williams was at age seven, but I do remember what an incredible impact the experience of Star Wars had on me at that young age. One particular musical moment I recall was fairly early in the film, when Luke Skywalker is looking at the twin suns setting, and contemplating his destiny. I would not have known at age seven that this sweeping music was the Force theme, or that John Williams composed it — that kind of awareness came later — but I certainly remember the impression it made on the very young me. I was ten years old in 1980 when The Empire Strikes Back was released, and I had that soundtrack on vinyl, so that would have been one of the earliest records I owned, and probably my earliest awareness of John Williams as a composer. By the mid-1980s, during my teenage years, I became very much aware of his work with the Boston Pops, and acquired a number of the iconic recordings he made with them — which of course included a great deal of music from his film scores. As I started to compose in my later teenage years, and especially in my early twenties, these recordings were very impactful on me, and on my sense of how an orchestra could sound.

You have said that your principal musical influences/models include the music of Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein and John Williams. Can you explain what is the line that connects these three American music icons? And why their music is so important to you?

It’s true that the musical works of Copland, Bernstein and Williams have been hugely influential on me. As an American orchestral composer, I suppose it’s not surprising that these major figures in that field would be principal influences. If one thinks about the idea of an “American sound” in orchestral music, certainly these three composers have been among the most important in establishing that American sound. I think it’s fair to say that there is a clear lineage between them, with Copland’s musical style strongly influencing that of Bernstein, and both Copland’s and Bernstein’s styles influencing Williams. Of course, there were also strong personal connections, with the relationship between Copland and Bernstein beginning from their meeting in 1937, and continuing throughout the rest of their lives. It’s hard to imagine Bernstein’s music without the example of Copland’s, and it’s also hard to imagine the ubiquity of Copland’s music without Bernstein’s advocacy of it as a conductor, including all the recordings, performances, television programs, etc. I believe also that the personal connection between Bernstein and Williams was an important one; and I think that that the personal connections of all three of them to Tanglewood and the Boston Symphony Orchestra (among other American institutions) constituted a kind of shared musical nourishment that bound them together in a certain way.

It can be difficult to articulate in words specifically what constitutes this musical lineage and the “American sound,” but certainly a clarity and directness of musical expression is an important factor. It can be easier to point to specific musical instances where one can hear these connections clearly — for example, Bernstein’s use of Copland’s Billy the Kid as a model in the closing scene of his score for On the Waterfront; or Williams’s use of Coplandesque touches in his scores for Saving Private Ryan and Lincoln (while still, of course, absorbing these into his own personal idiom).

As for the influence of these composers on my own music, I think this is a natural consequence of my having listened to so much of their work over the years, and having studied so many of their scores. Quite a lot of shelf space in my studio is devoted to scores by these three composers! As just one of many possible examples, my fondness for mixed meter writing in fast tempo music, such as in New Beginnings and the second “Scherzo/Dance” movement of my Symphony No. 1, clearly derives from Bernstein’s approach to this kind of mixed meter writing (though hopefully a personal voice of my own can be perceived in these pieces).

Talking specifically about John Williams’s music, what is about his writing, or his style, that touches you to the point of looking at him as a model?

There is so much that I could say in response to that question! I’ll mention a few key points.

First, John Williams possesses a melodic gift that I find truly astounding. For the many fans of his music, this may be a very obvious statement, but the ability to compose melodies which are compelling, distinctive and memorable is exceedingly rare, and I believe Williams is unrivaled among living composers in this respect. If one thinks of how many people around the world could immediately sing a number of tunes which he composed, one gets some sense of how profound is his gift. How many people around the globe could immediately sing the main themes from Star Wars, or Indiana Jones, or Harry Potter, or the “Flying Theme” from E.T.? The number of people who easily could sing any of these tunes is likely countless. This is a remarkable thing, and much too easily taken for granted, I think. He has composed a staggering number of great, memorable tunes. Among many, one that comes to mind for me is the melody of “Luke and Leia,” from Return of the Jedi, in its more expanded concert setting — extraordinarily lyrical and beautiful music. In terms of personal influence, I have worked hard to craft memorable melodies in much of my orchestral music, and Williams is the gold standard in this respect.

Second, Williams’s skills in creating musical drama and characterization are extraordinary. Of course, this is a big part of what has made his body of film music so compelling. His versatility in being able to create precisely the right kind of music to evoke a particular character, or to support a particular dramatic situation, is truly something to be admired. One thinks of the remarkable range of musical contrasts — for example, between the “feminine”, lyrical theme for Princess Leia and the menacing Imperial March in The Empire Strikes Back; or between the aleatoric elements and the tonal five-note “communication motif” in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. But his gifts for musical drama and characterization are not limited to his film music. Think of the contrast between the opening fanfare material and the more lyrical theme in the 1984 Olympic Fanfare and Theme, how evocative each musical element is, and how compellingly he alternates and combines these, evoking the grandeur and striving of athletic competition, and the nobility of this endeavor. There are many such examples in his body of work.

Third, Williams’s skills as an orchestrator are truly at the highest level. All of his orchestral music simply sounds so effectively, and it’s hard to overstate how important this is. As both an orchestral composer myself, and as an orchestrator for Hollywood composers, I have learned a great deal from studying the many Williams scores which are commercially published (in the Hal Leonard Signature Edition series). The availability of these scores for study is a great gift to the musical community, and clearly there have been many composers who have been influenced by this aspect of his work. Williams seems to have an unerring sense of orchestration, both in the most idiomatic use of individual instruments, and in the ideal combinations and voicings of instruments. In this sense, studying his scores can be as informative as studying the scores of Strauss, Ravel, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Britten among European composers, and Copland, Barber, Bernstein among American composers (to choose just a few examples). His orchestration skills place him among those masters, and there is so much to be learned from this type of study.

Very much so, yes. Also, John’s music sounds both simple and complex at the same time. Even straightforward tunes like the ‘Raiders March’ or the theme from Jurassic Park are constructed with a great sense of architecture and development. But mostly, his music seems to add emotions otherwise absent onscreen. Do you think he found in films an ideal place to develop a sense of personal style as well?

This is another big question, about which one could say so much. I think that some of what I mentioned earlier regarding musical drama and characterization is also relevant here. As you know, Williams has said in interviews that he has always strived to create musical and thematic material which is so closely married to the films for which he composed them, that one could not imagine the films without the music. This is a very high bar for a composer to set for himself, and I believe that he succeeded brilliantly time and again, and in very different contexts. In each case, I think that by seeking to serve the specific film that he was assigned to score, he found musical and stylistic solutions which perfectly suited those films; and the contrasts in subject matter, setting, and tone for the various films resulted in quite varied kinds of stylistic output.

As an extreme example of these stylistic constrasts, think of, say, Superman from 1978, and Memoirs of a Geisha from 2005. Each of these scores supports its film in what I think is an ideal way, and since these films are so stylistically different from one other, so too are the scores he composed for them. Listening to these two scores back-to-back, one might not immediately conclude that they were both from the same composer’s pen (or pencil!), though I think one would immediately recognize the level of craftsmanship in each. These scores are in hugely contrasting styles, yet somehow the personal voice of the composer is perceptible in each. And this is only addressing two film scores in his vast output, and not even mentioning the huge body of concert music. So I think it’s fair to say that Williams is capable of composing in multiple musical styles, which somehow all reflect his personal voice.

A few of your concert pieces, for example Silver Fanfare, Celebration Overture and Festivities, contain some really nice Williams-esque touches in a few spots (especially certain gestures in the brass), but always keeping your own voice. Is this the result of having absorbed John’s stylings by listening/studying to his music while exploring your own personal trait?

Yes, I suppose that’s true. Returning to an earlier point, having the opportunity to study Williams’s published scores, and to investigate his particular choices of orchestration, voicings, etc. — along with those of other composers whom I admire and respect — inevitably leads to some kind of assimilation of these elements. One comes to understand what really works in orchestral writing. It’s nice to hear you mention this, particularly about the brass. A number of folks who have written about my music have referenced my approach to brass writing, and this is something at which I’ve worked hard. Each of the pieces you mentioned is a celebratory piece (I’ve been asked to do quite a lot of those!), and of course Williams’s approach to celebratory music has more or less defined that genre in our time.

Following on this topic, one of the things that strikes me about your music is how much it bursts with optimism and enthusiasm — it’s always hopeful, rich with symphonic joy and exuberance, and I’d say it’s also genuinely American, as your brilliant Symphony No.1 shows very well. It’s not easy to find such qualities in contemporary orchestral music. Is this a natural consequence of your approach to music in general?

Thank you for these kind words. It’s probably fair to say that in some ways I’ve become known for optimistic and exuberant pieces, to use your words; though of course I’ve written other kinds of music as well. Some of this is simply a result of the kinds of commissions I’ve been offered, which have included a great deal of celebratory music. But I suppose that I naturally gravitate toward this kind of writing also. On some level, I enjoy composing music which reflects my own personal tastes, and which aims to give audiences the same sort of uplifting musical experiences which I have myself, when I listen to music that I find uplifting. And with the challenging state of the world these days, I think that the need for music (and other art forms) which can help uplift us is great indeed.

Has your work as an orchestrator for some major Hollywood film composers like James Newton Howard, Thomas Newman, and the late James Horner influenced your approach to writing for the concert hall?

The short answer to that question has to be “yes.” Certainly my love for both concert music and film music has informed my approach to orchestral composition; and the work I’ve done as an orchestrator for these extremely gifted composers has had an impact on my musicial sensibilities. I consider myself very fortunate to have had opportunities to orchestrate for some of the top Hollywood composers (working alongside their individual lead orchestrators), as this has allowed me to become quite familiar with the details of their musical approaches — at least with respect to the specific cues on which I’ve been asked to work. These opportunities to “look inside the workshops” of these highly prolific and successful composers, and to make some very modest contributions to their high-profile projects, have been personally meaningful to me, and I’m deeply grateful for this.

On two occasions, you had opportunities which might be considered as “following in the footsteps” of John Williams, with commissions from the Boston Pops and the United States Marine Band. Were those personally signficant opportunities for you?

Indeed, both of these commissioning projects were very special and personally meaningful ones, in which I was well aware of the specific Williams connections. In late 2009, when I received a call from Keith Lockhart inviting me to compose a work celebrating the legacy of the Kennedy brothers — JFK, RFK, and Ted Kennedy — for the 125th anniversary commission of the Boston Pops in 2010, it resonated deeply with me that I was being asked to write for the very orchestra whose recordings had so influenced me, and that the invitation was coming from John Williams’s successor. This was certainly in my mind as I composed The Dream Lives On: A Portrait of the Kennedy Brothers. When the Boston Pops landed the incredible trio of actors — Robert De Niro, Morgan Freeman, and Ed Harris — to narrate the piece I’d composed (with Lynn Ahrens working with me on the text), including for a recording and television broadcast, it took an already thrilling project to an even higher level.

A more recent commissioning project had me feeling that I was following even more directly in John Williams’s footsteps, when Colonel Jason Fettig, Director of “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band, invited me to compose a work celebrating the 220th anniversary of that esteemed ensemble in 2018. I was well aware that Williams’s work For The President’s Own had been composed to celebrate their 215th anniversary in 2013. I felt a bit intimidated by that fact, and also because this would be only my second-ever attempt at composing for concert band. Nonetheless, knowing that the invitation was a great honor, I felt I had to do my best to compose something worthy of the occasion. Happily the resulting piece, Fanfare, Hymn and Finale, seems to have turned out well, and was included on the Marine Band’s fall 2018 tour.

It’s a terrific piece, Peter, and it ties to John Williams not just because of the United States Marine Band connection, but also because it shares a kindred spirit to Williams’ approach when he writes in concert band-like mode, which in my opinion is a crucial aspect of his own voice.

Let’s move to your most popular work, Ellis Island: The Dream of America. It has become one of the most-performed American orchestral works of the last fifteen years, and recently passed its 200th performance. The work was nominated as Best Classical Contemporary Composition for a Grammy Award in 2005, and in May 2019, you were awarded with the Ellis Island Medal of Honor. It’s really a beautiful work, full of impassioned lyricism and profound meaning (and in this specific time of world history is even more relevant). The writing is richly thematic and colorfully orchestrated, like some of Williams’s Americana-styled concert music. And like Williams’s music, it seems to have touched a great many people. Can you explain why this work is so personal and meaningful to you?

Thank you again for your very kind words. Indeed, of all the works I’ve composed, Ellis Island has become by far the most performed and best known, and has been part of my life nearly every day for more than 15 years now. As you know, the work uses actors with orchestra, and they read the real words of real people — seven immigrants who came to the United States through Ellis Island from seven different countries between the years of 1910 and 1940, whose stories I found in the Ellis Island Oral History Project. And the work uses projected images as well. So the very nature of the piece is distinctive from purely orchestral music; it’s more of a theatrical-orchestral hybrid, though of course it’s meant to be performed on the concert stage. These stories are deeply compelling and moving, and certainly that has been a crucial factor in audiences’ widespread embrace of Ellis Island. Because I found these real stories so personally compelling, that inspired my best attempts to compose music worthy of accompanying those stories.

The nature of this work called for several contrasting musical styles and moods to appropriately accompany the stories, and to be used in the purely orchestral Prologue and interludes. But if there is one over-arching musical approach, it would be fair to call that “Americana-esque” — so again the influences of Copland, Bernstein, and Williams can be felt, though I hope that the voice is my own.

The work concludes with a recitation by all the actors of the classic Emma Lazarus poem “The New Colossus,” which appears on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty (“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…”). I composed this piece in 2001-02 (begun a few months before the 9/11 attacks), and needless to say, the world has changed a great deal since then. I could not possibly have foreseen the degree to which current events, particularly with respect to immigration, would have changed the present perspective on this work — as you say, it appears to be more relevant than ever, and that is something I am hearing from audiences around the United States. It was especially meaningful to me that PBS’ esteemed Great Performances series produced in 2017, and broadcast nationally in the United States in 2018, a special one-hour television program devoted to my Ellis Island, with a marvelous cast of actors, and the Pacific Symphony conducted by Carl St.Clair — who represents another John Williams (and Leonard Bernstein) connection.

Since at least 1977, the music of John Williams ignited a spark of sincere symphonic enthusiasm among young people around the world. He has inspired at least two or three generations to study music and pursue musical careers. There are many stories about people deciding to pick up an instrument after falling in love with the music of Star Wars, E.T., Jurassic Park or Harry Potter. What do you think John’s legacy will be in this sense? And what is he leaving specifically to the film music and the Los Angeles music community?

What you say is quite true, and I think it’s impossible to overstate the importance of John Williams’s legacy, to both the Los Angeles music community and the wider world. At recent concerts of his music at the Hollywood Bowl, David Newman, who conducted the programs, summed it up simply by saying: “There’s never been a career like this” — and of course that’s accurate. When one considers not only quantity and quality, but also longevity and universality of impact, I think it’s fair to say that John Williams is in a league of his own. The term “living legend” is one that can be much overused, but clearly it applies in his case. Of the innumerable highly gifted composers who have flourished in Los Angeles since the birth of the film industry, I believe that his career has been uniquely impactful. If one speaks to any of the extremely gifted studio musicians who have had opportunities to work with him over the years, each of these folks speaks of John Williams with a kind of genuine reverence. That says a great deal. It’s also wonderful that the Los Angeles Philharmonic has embraced and celebrated their special relationship with him in such powerful ways in recent years, and that they continue to do so. Living in Los Angeles, I feel fortunate to be able to witness and experience this.

Finally, what is the next musical project coming up for you?

At the moment, I’m hard at work on an important commissioning project from a major American orchestra, which will be premiered in the 2020-21 season. As it hasn’t yet been announced publicly, I can’t yet reveal any details, but it’s quite a challenging project, which will be announced in the coming months. Please stay tuned!

Thank you deeply for taking the time to talk with me, Peter. It’s been a wonderful conversation.

Thanks for inviting me to be part of this, Maurizio.

A very special thanks to Peter Boyer for his time and generous, kind spirit.

Visit Peter’s official website to get more information about his career, listen to excerpts from his works and to be updated about his upcomings works and conducting appearances: https://propulsivemusic.com/

You can listen to music by Peter Boyer on Apple Music, Spotify and on his own official YouTube channel.

Watch Peter Boyer sharing his story on BMI’s “Classical Music Month” special:

https://www.bmi.com/special/peter_boyer